John Buchan

CONTENT:

I. A Man on Kirkcaple Beach.

II. In Search of Fortune.

III. Blaauwildebeestefontein.

IV. My Journey to the Winter Pasture.

V. Mr. Wardlaw Predicts Coming Disasters.

VI. The Drum at Sunset.

VII. Captain Arcoll Tells His Story. VIII

. I See His Excellency John Laputa Again.

IX. The Trading Post at Umvelos.

X. I Go in Search of Treasure.

XI. Rooirand Cave.

XII. A Message from Captain Arcoll.

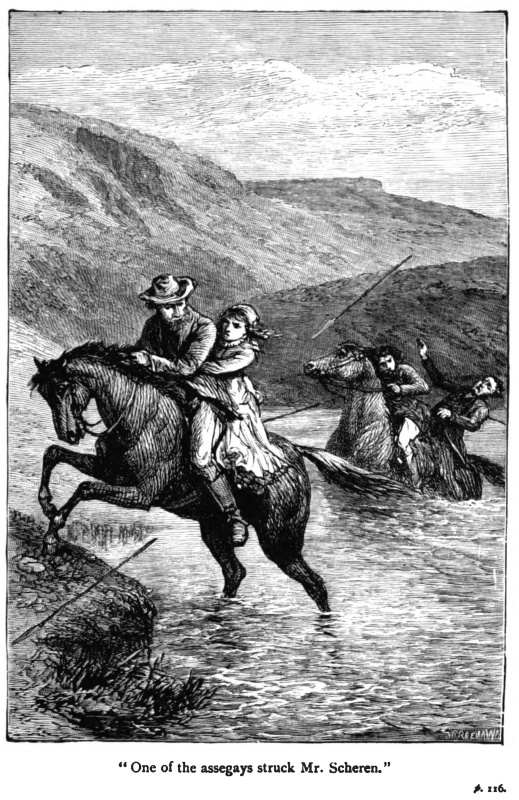

XIII. Letaba Ford.

XIV. I Have the Necklace of Presbyter John.

XV. A Morning in the Mountains.

XVI. Inanda Kraal.

XVII. A Barter and Its Consequences.

XVIII. How a Man Must Put His Entire Trust

in a Horse.

XIX. The “Shepherding” of Arcoll.

XX. I See His Excellency John Laputa for the Last Time.

XXI. I Climb the Rocks Once More.

XXII. A Great Danger Happily Avoided.

XXIII. My uncle’s gift is multiplying.

I.

MAN ON KIRKCAPLE BEACH.

I remember my first encounter with him as clearly as if it had happened yesterday. I could not have imagined then how fateful that moment would be, or how often that face I had seen in the dim moonlight would haunt me at night and disturb my peace during the day. But I still remember the paralyzing fear it produced, more intense than is really appropriate for boys who spend their time and play and disturb the peace of Sunday.

The town of Kirkcaple, where, as in the adjoining parish of Portincross, my father was vicar, stands on a hill on the shore of the little bay of Caple, with a view straight out to the North Sea. Around the headlands which enclose the bay, the coast forms a sort of breastwork of bare red rocks, where only small mountain streams make their way to the water’s edge. Below is a beach of the finest white sand, where we schoolboys of the town used to wade through all the warm seasons. But on long holidays we were wont to venture farther up the cliffs, for there were many deep hollows and pools of water, where you could catch valuable fish and search for hidden treasures at the cost of your knees and your trouser buttons. Many a Saturday I have spent in a cleft of the rock, burning a bonfire made of driftwood, and pretending to be a smuggler or a Jacobite just landed in France. There were always a few of us Kirkcaple boys together, all my age, among them Archie Leslie, the son of my father’s clerk, and Tam Dyke, the mayor’s nephew. We had sworn a blood oath to keep quiet about all our exploits, and each of us had a name that had belonged to some famous pirate or seafarer. I was Paul Jones, Tam was Captain Kidd, and Archie—it goes without saying—was Morgan! Our meeting place was a cave through which the mountain stream called Dyve Burn had cut its way into the rock on its way to the sea. There we would gather on summer evenings, and sometimes on Saturday evenings in winter, and tell great stories of our bravery, which greatly swelled our spirits. The simple truth, however, was that our exploits were of a very modest nature: a few fish and a handful of apples were our spoils, and a fight with the men of Dyve’s tannery was our greatest feat.

The spring break regularly fell on the last Sunday in April, and on that particular Sunday in question the day was unusually warm and sunny for the season. I had had enough of Thursday and Saturday services, and now there were two more on Sunday—too much for a twelve-year-old who could hardly sit still as the spring sun streamed through the windows into the gallery. There was still evening service, and it threatened to be doubly boring, for His Excellency Mr. Murdoch of Kilchristie, known for his long sermons, had taken my father’s turn to preach. No wonder I was ripe for Archie Leslie’s suggestion, which he made as we were going home for tea, that by developing a little cunning we might get out of all that. During communion, we did not sit in our own pews as usual, but each parishioner took a seat wherever he pleased. The vicar’s pew was full of Mr. Murdoch’s Kirkcaple relatives, whom my mother had invited to hear His Grace, and it was easy for me to get permission to sit in the gallery with Archie and Tam Dyke. But when the bells had stopped ringing, and we could tell by the sound of footsteps that the congregation had settled in the church, we crept down the gallery steps and slipped out by a side door. In a moment we were across the churchyard, and then we were running towards Dyve Burn as fast as we could.

All the “good” boys in Kirkcaple wore the so-called Eton dress, which consisted of long trousers, a short little coat and a top hat. I had been one of the first victims, and I shall never forget the first time I ran home from Sunday school dressed in it, with all the street boys in the town throwing snowballs at my top hat. Archie later suffered the same fate, for his parents faithfully followed suit. We were now dressed in these awkward outfits, and our first concern was to hide the hats in some easily remembered place under the juniper bushes on the hills. Tam had escaped the changes of fashion, so he wore a plain suit and breeches. He now took out his hitherto hidden treasure, which was to light our way on the journey, namely, a very powerfully smoking secret lantern.

Tam belonged to the Free Church, where confession fell on a different day from ours, and so he would not have been obliged to go to church now, which had been a burden to Archie and me. But strange events had happened that day in his church too. A black man, the Right Reverend John Jonkunminen, had preached. Tam was quite filled with this unheard-of incident. “A Negro,” he said, “a big black man, as tall as your father, Archie.” He was said to have beaten the pulpit with great success, and it was a wonder that Tam had stayed awake the whole time. The man had spoken of the heathens of Africa and said that in the sight of God a black man was as good as a white man, and he had predicted in vague terms the day when the English would learn one thing or another about civilization from the despised Negroes. Such had been the course of the discourse, at least according to Tam, who otherwise did not seem to really approve of the speaker’s opinions.

“That was pure nonsense, Davie. The Bible says the children of Ham shall be our servants. If I were a minister, I wouldn’t let a nigger in the pulpit. I’d draw the line at Sunday school.”

It was getting dark when we reached the heather-covered clearings on the ridge, and before we had reached the gently sloping headland that separates Kirkcaple Bay from the cliffs it was as dark as it could possibly be on an April night with a full moon. Tam would have liked it to be darker still. He took out his lantern, and at last, by a terrible waste of matches, succeeded in lighting a small stub of candle, after which he closed the lantern and pressed on cheerfully. We did not need any lighting until we reached Dyve Burn, where the path began to descend steeply along a cleft in the rock.

It was here that we first noticed that someone had gone before us. Archie was indulging in Indian books at this time, and never missed an opportunity to practice his art of scenting. He always kept his eyes on the ground, which often led to his finding coins, and once he found a small ornament that the mayoress had dropped. At the bend of the path is a small patch of ground covered with a thick layer of gravel thrown up by the waves. Archie was on all fours in the blink of an eye. “Boys,” he exclaimed, “this is a clear track,” and after a short examination, “a big, tall, and stilt-legged man has come down here, and he has been here only a short time, for the tracks are in the damp gravel, and the water has not yet completely filled them.”

We dared not doubt Archie’s keen observations, and our thoughts were occupied with who the visitor might be. In the summer you might meet people on a pleasure trip here who had found the firm white sand suitable for their purposes, but at this time of year and day no one, whoever they were, should have had any reason to trespass on our territory. The fishermen never came this way, for the lobsters were to be had on the east side, and the steep, bare headland at Red Neb made the road along the shore difficult to navigate. The boys from the tannery would occasionally come this way to bathe, but the tanner’s boy did not swim on a chilly April evening.

Yet there was no doubt where the stranger had headed. His steps led to the shore. The tracks, illuminated by Tam’s lantern, were clearly visible as leading down a slippery path. “Perhaps he has found our cave. It is best to proceed with caution.”

The secret lantern was closed and with the best smuggler’s gestures we crept down the cleft of the rock. The whole thing seemed a little mean, and I think we were all a little afraid at the bottom. But Tamilia had her lantern, and it would never occur to her not to complete an adventure, which was evidently of just the right kind. Halfway down, as we went, there was a small grove of stunted alders and hawthorns, the trees forming a sort of arch over the path. I know I felt a sense of relief in our hearts when we had passed this place without any major mishap, except that Tam stumbled a little, when the door of the lantern opened and the candle went out. We did not stop to light it, but continued on our way until we came to the long, smooth, reddish rocks that border the shore. We could no longer see any tracks, so we stopped sniffing and instead carefully climbed over a large cairn of boulders and descended further into the rock recess we called our cave.

There was no one in the cave. We lit a lantern and began to examine our gear. A couple of shabby fishing rods, some fishing line, a couple of wooden boxes, a pile of driftwood for a fire, and a few pieces of quartz in which we thought we saw gold,—that was all our modest equipment. Or perhaps I should also mention the cracked clay pipes filled with a horrible mixture that we sometimes smoked to be real people of the time. When all the brothers-in-arms were now assembled, a watch was sent out. Tam was ordered to go around the corner of the cliff where the shore could be seen, and to see if the coast was clear.

Three minutes later he came back, and in the light of the lantern we saw a look of dismay in his eyes. “There is a fire burning on the shore,” he said, “and there is a man standing by it.”

That was the news. Without wasting time in talking we rushed out. Archie first and Tam, who had closed his lantern, last. We crawled to the edge of the cliff and peered over it, and sure enough, there on the tide-washed and polished sand we saw a point of light and a dark creature moving about it.

The moon was just rising, and besides, there was that strange glow from the sea which is often seen in the spring. The fire was about a hundred yards away, a tiny flame which I would have put out with my hat. The fire was kept up, judging from the crackling and the smoke, with dry seaweed and unbranched branches taken from the woods. The figure of a man was visible beside the fire, and just as we stared at it, he began to circle the fire, first moving away and then coming closer again.

This sight was so unexpected, so completely different from anything we had ever seen before, that we were almost frozen with astonishment. What could this strange creature have done with fire at half-past eight on a Sunday evening in April on the shore by Dyve Burn? We discussed the matter in whispers behind a large boulder, but no one could solve the riddle. “Perhaps he has come ashore in a boat,” suggested Archie; “he may be a foreigner.” But I reminded Archie of the footprints he had made himself, which showed that the man had come from the landward side over the rocks down to the shore. Tam was convinced that he was a madman, and voted that we should set out at once.

But as if bewitched, we remained stuck in this silent world of sea, beach, and moonlight. I remember looking back at the black, solemn cliffs, and feeling inexplicably one with that unknown. What chance had brought this irrelevant creature to our territory? Strangely enough, I was more curious than afraid. I hoped to penetrate the depths of this mystery and find out what that creature could have to do with its fire.

Archie must have had the same thought, for he threw himself down and began to crawl quietly towards the shore. I followed behind, and Tam came last, uttering one or two objections. Between the rocks and the fire was first a strip of cobbles and slate about 200 feet wide, higher than the high tide mark, except perhaps during the strongest spring tide. Further on was a line of seagrass beds, and then came the hard beach sand. There were many good hiding places behind the large rocks, and in addition to the distance and the poor lighting, there was no danger of our being noticed, also because the man was too absorbed in his work to take special care of the observation point on land. He had chosen his spot well, for he could hardly have been noticed from anywhere but the sea. The rocks are grooved from below so that from above you can hardly see the sandy beach except from the very edge.

Archie, however, as an experienced skulker, was about to reveal us. His knee slipped on the seagrass, and he rolled down the boulder, the pebbles crunching along with him. We were as quiet as mice, afraid that the man had heard the commotion and would now go to investigate. But when, after a moment, I carefully raised my head, I saw that he was not at all disturbed. The fire was still burning, and he was circling it as before.

Right by the springs was a large red sandstone boulder with many cracks. Here we could take up excellent positions and all three of us crawled behind it so that only our eyes remained above its edge. The man was now barely twenty yards from us and we could clearly distinguish his body. He was large and rough-built, or so it seemed in the semi-darkness. He had nothing on but a shirt and trousers, and from the sound of his footsteps on the sand I could hear that he was walking barefoot.

Suddenly Tam Dyke let out a suppressed cry. “By God, that’s our black priest,” he said.

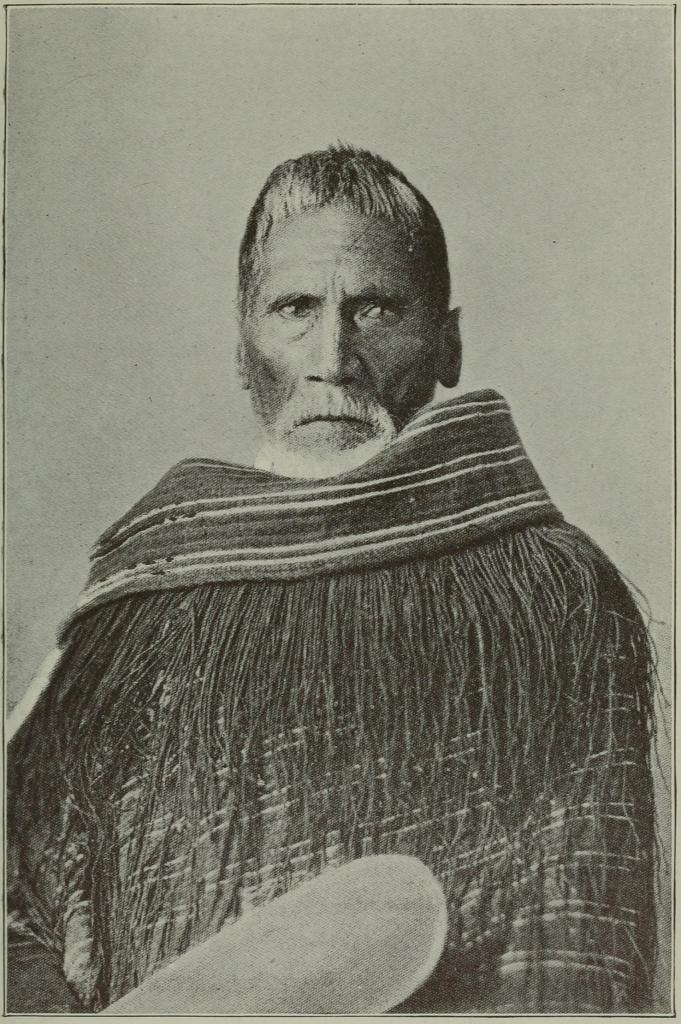

We saw now, as the moon came out of the clouds, that there was indeed a negro by the fire. His head was bowed, and he walked round the fire with measured, regular steps. After long intervals he stopped, raised both his hands towards the sky, and bowed towards the moon. But he did not speak a word.

“That’s magic,” said Archie. “He’s calling the devil right now. We’ll have to wait and see how this goes, because if we run any further now he’ll catch us. The moon’s too high.”

The man continued on his way as if he had heard a faint music. I had felt no fear when we were in the cave, but now that the adventure had come so close upon us, my courage weakened. There was something dreadful about that big negro, who had thrown off his priestly robes and was now practicing some kind of witchcraft alone on the seashore.

I was sure it was witchcraft, for there seemed to be something mysterious, unlawful in the air. But it was not long before he stopped in his rounds and threw something into the fire. A thick smoke rose from it, the aromatic scent of which we could smell, and when the smoke had cleared, the flame burned with a bluish silver glow reminiscent of moonlight.

There was no sound, but now he took something from his belt and began to draw some strange signs in the sand between the fire and the innermost circle. When he turned, the moonlight fell on the weapon, and we saw that it was a large knife.

We were now really beginning to get scared. Here we were, three boys, late at night, in a completely deserted place, only a few yards from a large wild man with his big knives. The adventure seemed to me anything but attractive, and even brave Archie was scared, judging by his pursed lips. As for Tam, his teeth chattered like a threshing machine.

Suddenly I felt something soft and warm on the stone under my right hand. I felt closer and noticed that it contained the stranger’s clothes, socks and shoes, a priest’s robe and hat.

This made matters worse, for by staying there until he finished his religious rites we could not avoid exposure. On the other hand, retreating over the boulders in the clear was equally daring. I whispered this to Archie, but he was willing to stay. “Maybe something will happen,” he said. That was what he always said.

I don’t know what might have happened, for we had no time to wait for it. Tam Dyke’s nerves gave way quite unexpectedly. When the man down there once turned towards us with his bows and crouching, Tam sprang up suddenly and shouted at him in one of the schoolboy’s slurs then in fashion in Kirkcaple: “Who called you chalk-faced, my thunder!” and, clutching his lantern, Tam fled at top speed, Archie and I following close behind. As we were leaving, I glanced behind me and caught a glimpse of a large creature, high and mighty, scuttling after us.

Although I saw his face only for a moment, I could never forget it afterwards. It was black as ebony, but not of the ordinary negro type. The lips were not thick, nor the nostrils wide. No, if I could believe my eyes, he had a boldly curved nose, and the features of his mouth were strict and precise. But his face at that moment expressed such astonishment, horror, and diabolical rage that my heart seemed to stop.

As I have said, we had a head start of about twenty or thirty yards. The rocky ground was to our advantage, for the boy can jump where a timekeeper would have to feel. Archie was the best of us at keeping his composure. “Run straight for the stream,” he shouted in a low voice, “he can’t follow us up the hill.”

We sidestepped the boulders, sped over red rock and sea-weed, and reached a little channel branching off the Dyve, which, having left its course, flowed over the flints. Here I looked behind me, but could see nothing. I stopped against my will, but this was nearly my undoing, for our pursuer had reached the stream before us, though some distance below, and was now coming up the hill to cut off our path.

I am generally a very rash person, and at that time I was even more so, owing to my lively imagination. But I think now that I have done a very brave thing, though more by instinct than by reason. Archie was the first, and had already waded across the flowing water. Tam followed him, and had just got over the stream when I saw the black man so near that he had only to stretch out his hand. In the next moment Tam would have been in his clutches, had I not let out a cry of warning, and run straight for the bank: Tam fell into the water—I could hear his grunt—but he got over, for I heard Archie calling after him, and then they both disappeared into the dense thicket that grows on the left bank of the stream. When our pursuer saw me on his side of the canal, he left the pursuit of the others, and now a race was started between us.

I was terribly afraid, but I was not hopeless, for all the crevices and hiding places on the right side of the riverbed were well known to me from our many expeditions. My feet were light and well trained,—I was considered the best long-distance runner in Kirkcaple. If only I could keep my head until I reached some familiar turn, I would be saved, for at such a point it was possible to turn off into a by-road behind a waterfall in the stream and reach one of our secret paths in the bushes. I literally flew up the steep mountain slopes without daring to turn, but at the top, where the rocks begin, I caught a glimpse of my enemy. The man could run, though he was heavily built. I had only five or six yards ahead of me, and I could already distinguish the flashing whites of his eyes and the red gums. I noticed something else—a shiny object in his hand.

Fear gave me wings, — like a seagull I flew up the rocks, climbed and leaped, striving towards that familiar turn. Instinctively I felt that my pursuer was growing weary, and for a moment I stopped again to glance behind me. But for the second time this movement was to be my last.

A large stone whizzed through the air and met the rock face within an inch of my head, so that the fragments of stone blinded my eyes. But now I was furious. I crawled lower, crept under a ledge, until I had reached a convenient spot, from which I saw my enemy climbing the same way I had come, with a terrible crashing of stones. I caught a loose stone in my hand and threw it at him with all my strength. It broke before it could reach him, but to my great joy he got a good chunk of it in his face. But then terror got the better of me. I crept around the waterfall into the woods and began to make my way towards the summit.

This last journey seemed the most difficult, for my strength was beginning to fail me, and I still thought I heard the pursuing footsteps at my heels. My heart had leapt into my throat as I pushed through the thicket of hawthorn, heedless of the ruin of my best clothes. At length I found the path, and to my great relief met Archie and Tam, who had slackened their pace, much concerned for my fate. We now joined forces, and soon reached the top of the cliffs.

Now we dared to look behind us. Our pursuer was tired, and far below we heard the sound of footsteps heading towards the shore.

“You’re in your blood, Davie. Did he get close enough to hit you?” Archie asked.

“He threw a stone, the pieces of which hit me. But I gave him back the same amount. He’ll remember this evening because of his nose, if nothing else.”

We did not dare to go over the hills, but went straight to the nearest human habitation, a country manor a short distance inland, and when we got there, we threw ourselves down beside a meadow gate to rest.

“I’ve lost my lantern,” Tam said, “You worthless black beast.

Wait until I get up to talk about your business at home.”

“It won’t come to anything,” said Archie confidently. “As it is, he knows nothing about us, and can’t take revenge on us in any way. But if he somehow knows who we are, he’ll certainly murder us.”

Archie required us to take a vow of secrecy, which we were very happy to do, for we thought he was quite right. Then we found the country road and headed for Kirkcaple, the fear of homecoming gradually dispelling our fear of the unknown black man. In our excited state of mind, Archie and I completely forgot that our hats were resting under a bush on the hills.

Fate had decreed that our prank should not go unnoticed. It was our bad luck that Mr. Murdoch should have a bad stomachache immediately after the second hymn, and the congregation had quickly dispersed. My mother had been waiting for me at the exit, and when I was not heard from, she had gone to fetch me from the gallery. Thus the truth came out, and even if I had only taken a quiet walk to the rocks my unauthorized absence would have been punished. When, in addition, I arrived home with scratches on my face, no hat, and many tears in my best trousers, one can easily understand mother’s feelings. I received a few substantial slaps, and then I was put to bed and promised a truly magnificent punishment as soon as father came home.

The next day before breakfast my father was home and I got a good spanking. Then I went to school with the usual Monday gloom in my mind, reinforced by the gentle, compelling members. At the corner of the lower street I met Archie watching some vehicles coming down the street. In the carriage were two men, namely the Free Church minister—he had married richly and could keep a horse—who was driving the black preacher from yesterday. Archie and I quickly turned around behind a fence, from where we could take a last look at our enemy in complete safety. He was dressed in a priest’s uniform, with some thick furs on his head and a brand-new yellow leather bag by his side. He spoke loudly as the vehicles drove past us and the Free Church minister listened attentively. I heard him say something in his deep voice about “the influence of the Spirit of God in this place.” But what I particularly noticed—and this observation alone made me forget my compelling antics—was that one of his eyes was badly scarred and there were two strips of plaster crossed on the other cheek.

II.

GOOD LUCK IN YOUR SEARCH.

In this modest narrative, there are more than enough remarkable events to occur before the end, for me to be permitted to digress into quite ordinary matters. I will briefly relate what happened after I had seen “The Man on Kirkcaple Beach” until it was decided that I should go to Africa.

I remained at school for three more years, where my progress was more evident in sports than in mathematics. One after another I saw my peers leave their boyhood and enter the profession of a trade. Tam Dyke twice accompanied a Dutch schooner that used to load coal in our harbour without permission, and finally his father gave in to the boy’s will, when Tam was allowed to join the merchant navy. Archie Leslie, who was a year older than me, showed a tendency to law, and was therefore sent to a solicitor’s office in Edinburgh, where he was also to attend lectures at the college. But I remained at school, until at last I sat there alone with myself in the highest class, feeling myself utterly abandoned. I was a very solid young man, and my excellence at rugby football was known not only in Kirkcaple and Portincross. To my father, I was somewhat of a miscalculation, as he had hoped that his son would develop the same quiet, bookish nature that he himself had.

One thing I had firmly resolved in my mind: I would choose the career of a reader, however little I was inclined to study. My rapid progress depended solely on my fear of possibly having to sit in some office or other such position, which fate had already befallen several of my companions. And so I decided to study for the priesthood, not from any attraction to this holy calling, but simply because my father was a priest. This resulted in me being sent, when I was sixteen, to Edinburgh College for a year’s further courses, and the following year my studies at the university began.

If fate had been kinder to me, I might have ended up a learned man after all. I had begun to immerse myself in the study of philosophy and dead languages with a lively interest, but then my father unexpectedly suffered a stroke and died, and I had to start earning my own bread.

My mother had not much to live on, for my father’s income had not been sufficient for savings. When everything was arranged, it was found that my mother would receive only about fifty pounds a year. With the slightest demands, this would not have been enough to support the household, let alone my studies. Just when we had gotten this far in our affairs, an older relative of ours, a wealthy old bachelor, proposed to my mother that she should come and manage his household. As for me, he promised to get me a position in some larger firm, for he had many connections in the business world. What could we do but thank him and accept the offer. We sold our furniture and household goods, and moved into his rather gloomy apartment on Dundas Street. A couple of days later he announced at the dinner table that he had now found me a position that would be a good start.

“You know, Davie,” he said, “that you don’t understand the simplest business principles. There isn’t a shop in the whole country that will take you into anything but a cheap job, and your income will probably never rise above £100 a year. No, the only thing you can do now is to travel somewhere where a white man is valued. By permission, I met my old friend Thomas Mackenzie yesterday, who was with his solicitor on a farm deal. He is the manager of one of the largest trading and shipping firms in the world—Mackenzie, Mure & Oldmeadoros—perhaps you have heard the name. Among many other things, he owns at least half of all the small shops in South Africa, where everything imaginable is sold, from Bibles to fishhooks.

Now it seems they would rather have their own people from home to run those shops, and — to get to the point — when I mentioned you to him, he promised you a place. Today I received a telegram confirming the offer. You will be assistant store manager (here my uncle took some paper from his pocket and then read it) at Blaauwildebeestefontein. Well, the name is enough for you, I suppose.»

In this everyday way, I first heard talk about the place where such strange things were to happen to me.

“This is excellent for you,” my uncle continued. “You will be an assistant at first, but as soon as you get the hang of things you will have your own shop to run. Mackenzie’s shop will pay you £300 a year and when you get your own shop you will get a fixed percentage of the sales. You will have complete freedom to open new branches among the natives. I have heard that Blaauw… whatever it was again is up in the northern Transvaal and you can see from the map that it is a wild, mountainous country. Perhaps you will find gold and diamonds up there, and then when you get home you will buy the whole of Portincross.” My uncle rubbed his hands and smiled contentedly.

To tell the truth, I was both happy and sad. When I had to interrupt my reading, I preferred a shop table in the Transvaal to an office chair in Edinburgh. If I had not felt so deeply the loss of my father, I should have rejoiced only in seeing new lands and peoples. In this respect I felt somewhat exiled. That evening I took a long walk over the Braid Hills, and when I saw the Fife coast in the bright spring sunshine, and remembered Kirkcaple and my boyhood, I might have sat down and wept.

Fourteen days later I set out. My mother bid me a mournful farewell, and my uncle, who had bought me a suitable suit and paid for my fare, gave me a present of twenty sovereigns. “You wouldn’t be your mother’s son, Davie,” he said, “unless you brought home a thousand times as much.” I remember thinking at that moment that I would give more than £20,000 to stay on the windswept shores of the Forth.

I had chosen a ship that went direct from Southampton, and to be economical I travelled on the middle deck. Fortunately, all my homesickness soon gave way to another illness. It was almost a storm before we had even got out of the Channel, and at Ushaut there was such a gale that I never wanted to be in again. I lay dying in my cabin, unable even to think of food, and too weak to lift my head. I wished I had never left my home, but I was so ill that if I had had to choose between a trip home and a quick landing, I would have chosen the latter.

It was not until we got into calmer waters off Madeira that I had improved enough to sit up and observe my fellow-passengers. There were about fifty of us on the middle deck, chiefly women and children, who were travelling to visit relatives, and besides a few emigrant artisans and farmers. I soon became acquainted with a slight man with a yellow beard and spectacles. He came up to me and spoke to me in a Scotch dialect that was distinct from the weather. He was Mr. Wardlaw, from Aberdeen, who was travelling south to take up some school-teaching post. He was a well-bred man, having taken some university degree, and had served for some years as a sub-teacher in his native town. But the biting east wind was not good for his lungs, and he had gratefully accepted an invitation to a poorly paid country school in South Africa. When I asked him more specifically where he was going, I was greatly surprised to receive the answer: “To Blaauwildebeestefontein.”

Mr Wardlaw was a fine little man, sharp-tongued and cheerful. He spent his days studying the Dutch and Kaffir alphabets, but after dinner we used to walk about on the quarterdeck and talk about the future. He knew no more about the country we were going to than I did, but he was insatiably curious, and he piqued my interest. “This place, Blauwildebeestefontein,” he used to say, “is high up in the Zoutpansberg mountains, and as far as I can tell, not ninety miles from the railway. According to the map, there should be plenty of water there. The shipping company’s general manager told me the climate was healthy, and I wouldn’t have taken the place otherwise. We are coming among aboriginal tribes; I have a whole list of the chiefs here; ‘Mpefu, Sikitolu, Majinje, Magata’; and to the east of us there are no whites at all, on account of the fever, you see. The name means “spring of the blue wild beast,” and what a monstrous creature that wildebeest must be! This sounds like quite an adventure, Mr. Crawfurd. You can go into the pockets of the blacks, and I’ll see what I can possibly do to their souls.”

There was another passenger on the middle deck, to whom I paid attention because he seemed so repulsive to me. He was also a small man, named Henriques, and by appearance the biggest scoundrel who ever wore a pair of shoes. His face was the color of French mustard—dirty green—and he had bloodshot, round eyes, the whites of which were yellow with fever. His moustache was waxed, and as he walked he glanced about him furtively and curiously. We generally paid little attention to our appearance on the middle deck, but he always wore gleaming white underwear and pointed yellow shoes that matched his complexion. He spoke to no one, but smoked large cigars all day long in the stern of the ship and studied his greasy notebook. Once I bumped into him in the dark and he turned to me, cursing and growling viciously. I responded quite stiffly and he looked like he wanted to stick a knife in me.

“I’ll bet that thing was a slave trader sometime in his life,” I said to Mr. Wardlaw, who replied, “Then may the Lord have mercy on his slaves.”

And now I must relate an incident which made the remainder of the voyage seem far too short to me, and which foreshadowed the strange events to come. It happened the day after we had passed the equator, and the first-class passengers were amused themselves with all sorts of games on deck. A tug-of-war had been arranged among all three classes of passengers, and half a dozen of the strongest men on the middle deck, myself among them, had been invited to take part in the contest. The day was scorching hot, but the promenade deck had a sunshade and a fresh breeze was blowing. The first-class easily defeated the second-class, and, after a fierce struggle, the middle deck as well. We were then offered ice-cold drinks and cigars in honor of our victory.

I was at the extreme end of the spectators when my eye fell upon a person who did not seem to be paying any attention to the sport. A large man, in a priest’s habit, was sitting on a deck chair, reading. There was nothing else remarkable about him, and I do not understand what whim made me want to see his face. I took a few steps closer and then noticed that the man was black. As I approached a few steps closer he suddenly looked up from his book. And before me was the very face that had nearly scared the life out of me a year ago on the shores of Kirkcaple.

I spent the rest of the day in a state of apathy. It was clear that this scene was predestined. Here sat the man as if he were at least a well-to-do first-class passenger, and all outward signs pointed to a respected social position. I alone had seen him sacrifice to foreign gods in the moonlight. I alone knew the wickedness of his heart, and that one day this knowledge would be of use to me, I was sure.

I was a friend of another engineer, and I asked him to look up the name of my old acquaintance in the passenger list. His name was marked “The Right Honourable John Laputa,” with Durban as his destination.

The next day was Sunday, and who else would have been chosen to preach to us passengers on the middle deck if not a Negro priest! The captain himself, a man of great piety, introduced him, and spoke at the same time of the work which this brother of his had done among the heathen. Some were offended, and did not wish to be subjected to the eloquence of the black man. Mr. Henriques, in particular, whose complexion, from a distance, spoke of a kinship with Mr. Laputa, made objections peppered with curses against the insult. Finally, he sat down on a pile of rope and spat contemptuously in the presence of the preacher.

As for myself, I was very curious and also a little fascinated. The man’s face commanded as much respect as his body, and his voice was the most wonderful that ever came from a human mouth. It was deep and clear, gentle as a lovely organ note. He had none of the usual features of a negro, but instead an Arabian with a hawk nose, dark flashing eyes, and a cruel, determined mouth. He was as black as my hat, but in other respects he was a type of Crusader. I have no idea how he preached, though I heard from others that the sermon had been excellent. All the time I watched him and said to myself: “You chased me at Dyve Burn, but I gave you a memory.” Even I fancied I saw a thin scar on his cheek.

The next night I had a toothache, which kept me from sleeping. It was so warm that I could hardly breathe under the roof. So I got up, lit my pipe, and went to the quarterdeck to get away from the trouble. It was perfectly quiet,—only the sound of the waves against the regular thud of the propellers and engines was heard. A large yellow moon and a flock of pale stars looked down upon me.

The moonlight made me think again of the old story from Dyve Burn, and as usual I began to think of the Right Reverend John Laputa. I enjoyed the idea of being on the trail of some secret to which no one else had the key. I promised myself to find out about the priest’s business when we got to Durban, for I had a relative there who might be supposed to know him. Then, as I went down the gangway to the lower deck, I heard voices, and looking over the rail I saw two men sitting in the shade just beyond the hatch.

At first I thought it was two sailors cooling off, but something about the other seemed familiar to me, so I looked again. And in the same instant I had crept over the quarterdeck to a spot just above them. For those two were the black priest and the ugly yellow scoundrel Henriques.

I had no scruples about listening, but I did not gain much from their conversation. They spoke in low voices, and in some language which might have been Kaffir or Portuguese—in either case equally strange to me. I lay curled up and restless for many minutes, and was already tired of the whole thing, when a very familiar name struck my ear. Henriques said something, in which I distinguished the word “Blaauwildebeestefontein.” I listened attentively, and there could be no mistake. The priest repeated the name, and for the next two minutes it occurred frequently in their conversation. I crept back to my cabin, and thought so hard that my aching tooth was forgotten. I knew, first, that Laputa and Henriques were allies, and, second, that the place to which I was going had something to do with their plans.

I said nothing to Mr Wardlaw, but devoted the next week to the relentless work of an amateur detective. I procured maps and books from a friend of mine who was a mechanic, and read everything I could lay my hands on concerning Blaauwildebeestefontein. Not that I found much of that, but I remember feeling a strange thrill when one day I noticed from the charts that we were on the same latitude as the above-mentioned place. I could not, however, find out anything about His Excellency John Laputa. The Portuguese was still puffing his cigarette on the quarterdeck, fingering his greasy notebook, the priest was sitting in his deck chair, reading thick volumes from the ship’s library. No matter how hard I tried to keep an eye on them, I never saw them together again.

At Cape Town Henriques left the ship and never returned. The priest did not move from the ship during the three days we were in port, and I think he was in his cabin the whole time. In any case, I did not see his tall figure on deck until we were rocking in the roaring sea off Cape Agulhas. I was again seized with seasickness, and, except for our brief stops at Port Elizabeth and East London, I lay miserable in my cabin the whole time until we came in sight of the steep rocky coast off Durban.

Here I had to change ships, for reasons of economy I had to continue by sea to Delagoa Bay, and then take the cheap railway to the Transvaal. I first sought out a relative of mine who lived in a fine house near Berea, and found there a comfortable resting-place for the three days I remained in the town. I tried to question Mr. Laputa, but could get no information. There was no native priest of that name, said my cousin, who was an expert in these parts. I described the man’s appearance, but that was no help either. No one knew him—”probably,” said my cousin, “he is one of those American-Ethiopian rascals.”

I also found the manager of our company in Durban. His name was Mr. Colles, a big, stocky man, who received me in his shirt sleeves, a cigar in his mouth. He was very kind to me and took me home for dinner.

“Mr. Mackenzie has written about you,” he said. “I will speak to you quite frankly now, Mr. Crawfurd. The company is not at all pleased with the way our affairs have been conducted of late at Blaauwildebeestefontein. The country itself up there is no worse, and there are great opportunities there for a man who knows how to make the most of them. Japp, who is there now, is old and getting bored, but he has been in our service so long that we would not wish to offend him. In any case, he must go very soon, and then you will have every chance of getting a place, if you will only prove yourself a good man.”

He told me one thing and another about Blaauwildebeestefontein, mainly details about the business. In passing he mentioned that Mr. Japp had changed his assistants quite frequently in recent years. When I asked him the reason for this, he hesitated to answer.

“Yes, it’s very lonely there and they haven’t been happy. There aren’t any white people around and they would have liked some company. They complained and got a transfer. But their stock didn’t rise in the eyes of the company.

I told him that I had been dating a new school teacher on the ship.

“That’s right,” he said thoughtfully, “the school has been empty quite often lately. What kind of man is this Wardlaw? Do you think he’ll stay where he is?”

“From everything I’ve heard,” I said, “

Blaauwildebeestefontein doesn’t seem like a very popular place.”

“No, that’s true. That’s why we brought you there. No one born in the colonies can be comfortable in such surroundings. He wants a lot of company, and he doesn’t like the natives being so close to him. There are only natives up there and a few Dutch farmers, and some of them are mixed. But you young men from home are better off in such a demanding life, or you wouldn’t come here.”

Something in Mr. Colles’s voice made me ask one more question.

“What’s the matter with that place, then? There must be something more than loneliness, I think, to see how everyone has left so suddenly. I’m sure I’ve decided to stay here, and I’m going to stick to my decision, so you don’t have to be afraid to tell me everything.”

The chief looked at me sternly. “I like that kind of talk. You seem to have a stiff back, and I think I can talk straight. There ‘s something crazy there. Something that makes the average man nervous. What it is, I don’t know, and even those who come out of there don’t know. Now I want you to get everything straight. You would do the company an unspeakable service if you could find out. Maybe the “something” is in the natives, or maybe it’s the “burden,” or something else. Only old Japp seems to be able to stand it, and he’s too old and bored to move away. Just try to keep your eyes open now and write to me privately if you need any help. I see you haven’t come here for health reasons, and now you have a chance to put your foot on the step.”

“Remember that you have a friend in me,” he said later, as we parted at the garden gate. “Take my advice, and don’t be in too much of a hurry. Speak as little as possible, don’t touch the strong, learn as much of the language as possible, but act as if you don’t understand a word. You will surely get somewhere. Goodbye, my boy,” and he waved his fat hand at me.

That same evening I boarded a cargo ship that was touring the coast to Delagoa Bay. The world is not a big place—at least not for us wandering Scots, for who else would I have met on board but my old friend Tam Dyke, who was second mate on board! We shook hands, and I answered his questions about Kirkcaple as best I could. I had supper with him in the cabin, and then climbed on deck to see the ship being pulled off the beach.

Suddenly there was a commotion on the quay, and a large man was seen making his way to the gangway with his handbag. The men who were just untying the ropes tried to stop him, but he pushed forward, explaining that he had to see the captain. Tam went forward and politely asked the newcomer if he had booked a trip in advance. The newcomer admitted that he had not, but said he would check with the captain in two minutes. For some reason, best known to himself, His Excellency John Laputa left Durban in greater haste than he had arrived.

What he said to the captain I don’t know, but he got on board, and on top of that Tam had to move his cabin to make room for him. And this particularly annoyed my friend.

“That black animal must be made of money, for he paid extra, I’m sure of it. The old man doesn’t love his black brothers any more than I do. Things are bad if we start loading up on niggers now…”

I had all too little time to enjoy Tam’s company, for the next evening we reached Lorenzo Marques. This was now my final landing-place in Africa, and I remember how eagerly I looked out over the flat green shores and the shrubby slopes of the mainland. We were put ashore in small boats, and Tam came with me to spend the evening with me. By this time my homesickness was completely cured. I had a task before me that promised to be more interesting than my studies in Edinburgh, and I was as eager to reach my destination as I had been to leave England. My head full of secrets, I watched every Portuguese beggar and dock-boy as a spy, and when I had drunk a bottle of Collares liqueur with my coffee with Tam, I felt as if I had finally come into the world.

Tam took me with him to a friend of his, a Scotchman named Aitken, who was the agent of a large mining company at Thea Rand. He was from Fife and greeted me heartily, for he had heard my father preach in his youth. Aitken was a strong, broad-shouldered man, who had served in Gordon’s regiment, and had then been on various secret missions at Delagoa during the war. He was also a hunter and had traded all along the coast of Mozambique, and knew every Kaffir dialect. He asked me where I was going, and when he got my answer he had the same look in his eyes as he had seen in the section chief at Durban.

“It’s a tricky place you’re coming to, Mr. Crawfurd,” he said.

“Yes, I have heard it said so. Do you know anything about it?—You are not the first to have seemed mysterious at the sound of that name.”

“I have never been there,” he said, “although I have been very near it on the Portuguese side. That is the peculiar thing about Blaauwildebeestefontein, that everyone has heard of it, but no one has been there.”

“Wouldn’t you like to tell me what you’ve heard?”

“Yes, I know that the natives are a little strange up there. There is some sacred place there that every Kaffir from Algoa Bay to the Zambezi and beyond knows. In my hunting trips I have sometimes met Kaffir herds from the most remote regions, and they have all been either going to Blaauwildebeestefontein or coming from there. It is like Mecca to the Mohammedans, a place of pilgrimage. I have also heard of an old man up there who is supposed to be 200 years old. Yes, there must be some kind of witch doctor or magician up there in the mountains.”

Aitken smoked in the silence for a moment, then said: “There is one more thing I want to say. I also think there is a diamond mine there. I have often intended to travel there and investigate the conditions.”

Tam and I asked him to explain in more detail, which he did in his usual way.

“Have you ever heard of the LTK—the Illegal Diamond Hand?” he asked. “You see, it is a well-known fact that the Kaffirs often run away from the diamond fields with a great many precious stones, which they then sell to Jewish and Portuguese buyers. It is illegal to trade with them, and when I was in the Secret Police here we had a great deal of trouble about this illegal trade. But I did make one observation, namely, that nearly all the stones I got my hands on came from the same locality—nearer or farther from Blaauwildebeestefontein, and there is no reason to suppose that they were all stolen from Kimberley or The Premier. Moreover, some of the stones that passed through my hands were quite different from those I had previously seen in South Africa. I should not be at all surprised if the Kaffirs in the Zoutpansberg had found a rich vein, and they are wise enough to keep quiet. “One fine day I will travel up there to greet you and at the same time I will clarify the matter.”

The conversation then turned to other topics until Tam, thinking about the injustice he had suffered, asked something of his own accord.

“Have you ever met a big, tall native priest named Laputa? He came on board by force when we left Durban, and I was allowed to give him my cabin.” Tam described the man thoroughly and vindictively, adding: “Surely he couldn’t have had good intentions.”

Aitken shook his head. “No, I don’t know who he might be. You said he landed here. Well, I’ll keep an eye on him. You don’t see big native priests everywhere.”

Then I asked him about Henriques, of whom Tam had not yet heard anything. I described his appearance, his clothes, and his manners. Aitken laughed out loud.

“Most of His Majesty the King of Portugal’s subjects would fit those characteristics. If he is as you think he is a villain, you may be assured that he is with the LTK, and if my assumptions about Blaauwildebeestefontein are correct, you will hear from him sooner or later. Write me a line or two if he should happen to surface, and I will find out his record.”

I followed Tam to the ship with a light heart. I was content with the state of affairs as it was. I was on my way to a place that held some secret which I was determined to reveal. The natives around Blaauwildebeestefontein were very suspicious and it was possible that there were diamond fields in the area. The Henriques had something to do with the place and so did John Laputa, of whom I knew a strange thing. Tam knew it too, of course, but he had not known his former tormentor and I had not said anything. I knew two people, Colles in Durban and Aitken in Lorenzo Marques, who were ready to help me if I got into trouble. On the whole, it all seemed to be shaping up to be an interesting adventure.

The conversation with Aitken had given Tami a hint of my musings. She said goodbye to me, urging me to let her know if anything happened.

“I understand you are getting into some trouble.

Let me know if anything happens, I will come to you immediately,

even if I have to give up my place on the ship. Send a letter to the agent

in Durban if we happen to be in port. You haven’t forgotten Dyve

Burn, have you, Davie?”

III.

BLAAUWILDEBEESTEFONTEIN.

“Christian’s Journey” was the title of one of my childhood Sunday readings, and when I first saw Blaauwildebeestefontein, a passage from it clearly came to my mind. It was the passage where it is said that after many dangers Christian and Hopeful finally reached the Sweet Mountains, from where they could see Cana.

After many dusty miles on the railway, and a weary journey in the Cape Carts through dry plains and barren, rocky passes, I had suddenly arrived at a sweet, verdant harbour. The “Blue Wild Beast Spring” was a clear, roaring little rapid, flowing over blue rocks into deep lakes bordered by ferns. All around was a high plateau, on which grew lush grass, where marigolds and lilies flourished instead of the native beauties and dandelions. Dense, tall-tree jungles dotted the hillsides and meadows, as if the whole landscape had been arranged by a gardener. Farther on the valley dropped steeply to a plain that receded towards the horizon like a thick mist. To the north and south I noted the formation of the mountains: sometimes it rose up as a sharp peak, sometimes it spread out like a horizontal bluish rampart. At the extreme edge of the plateau, where the road just began to descend, were the huts that formed Blaauwildebeestefontein. The fresh mountain air had completely intoxicated me, and now the lovely floral scents of the evening added to my intoxication. Whatever snake appeared here, I had certainly come to Eden.

There were only two buildings in Blaauwildebeestefontein that looked civilized; a general store on the left bank of the river, and opposite it on the other side of the road a schoolhouse. Otherwise there were about twenty native huts, all higher up on the slopes. They were of the kind the Dutch call rondavels. The schoolhouse was surrounded by a beautiful garden, but the general store stood in a bare, dusty spot, with only a few outhouses and shelters around it. In front of the door were a couple of old ploughs and empty barrels, and under a solitary gum tree was a wooden bench with roughly carved tables. Small native children were playing in the sand, and an old Kaffir was sitting by the wall.

My meager travelling baggage was soon lifted from the cart and I went straight to the shop. It was the usual pattern: in one corner was a counter with regiments of bottles, and on the wall shelves a number of tins and all sorts of small merchandise. The room was empty and the air on the sugar box was black with flies.

There were two doors at the back of the room. I opened the right-hand door at a sharp turn and found myself in a sort of kitchen, with a bed in one corner and a bunch of dirty plates on the table. A man was lying on the bed, snoring heavily. I went closer and saw that he was an old, bald man, dressed only in a shirt and trousers. His face was red and puffy and he was breathing irregularly. The room smelled of bad whisky. I realised that this was Mr Peter Japp, my boss, and I immediately knew why business was going badly in Blaauwildebeestefontein: the manager was a drunkard.

I returned to the shop-room and tried the other door. It led into a small bedroom, which was clean and attractive. A little native girl—Zeeta, they called her—was tidying up the room, and looked pretty as I entered. “This is your room, baas,” she said in good English when I inquired. She must have been very intelligent, for there was a large pot of flowering nerium on the cupboard, and the bedclothes were immaculately white. She brought me some washing-water, and then a cup of strong tea, while I carried in my things and paid the driver. When I had cleared myself of the dust of my journey, I lit my pipe and went across the road in search of Mr. Wardlaw.

I met a schoolmaster under his own fig tree, examining one of his many kaffir monkeys. Having come direct by rail from Cape Town, he had already been there a week and was now the second oldest white resident of the place.

“You’ve got a fine boss, Davie,” were his first words. “He’s been as full as the Baltic Sea for the last three days.”

I cannot say that Mr. Japp’s vice has caused me any deeper sorrow. One man’s death is another man’s bread, and if he should prove impossible, it would only be to my advantage. But the schoolmaster took the matter from another side as well. “He is the only white man in the whole town, except us,” he said, “and it seems as if he would make no more special addition to society.”

The school was a farce. It had five white children from Dutch farming families in the mountains. The second section was better equipped, but the missionary schools in these parts attracted more natives. Mr. Wardlaw’s educational zeal was burning high. He planned to set up a workshop and teach carpentry and horse shoeing, neither of which he himself knew the slightest thing about. He praised the intelligence of his pupils and bitterly complained of his lack of knowledge of their language. “Davie,” he said, “we must both take a firm hold of language studies, for it will be to our advantage. Dutch is not difficult, it is a sort of kitchen language that you can learn in a week or two. But the native languages are a tough nut to crack. The main language here is Sesotho, and I have heard that once you know that, it is easy to learn Zulu. Then we must learn this thing the Shanquans speak—I think it’s called baronga. I’ve caught up with a baptized Kaffir in the huts up there who comes every morning and talks to me for an hour. It’s best if you come along.

I promised and then went back across the road to the shop. Japp was still sleeping, so I let Zeeta bring a cup of porridge into the room, and then I went to bed.

The next morning Japp was sober and made me some sort of apology. He explained that he had a constant backache, for which a glass of wine now and then was the best medicine. Then he began to acquaint me with my duties in an exaggeratedly friendly tone. “I liked you from the first moment I saw you,” he said, “and I think we’ll make good friends, Crawfurd. You’re a good boy who won’t stand any nonsense, I can see that. The Dutch here are a nasty bunch and the Kaffirs are even worse. Trust no one, that’s my motto. That’s what our name says, and I’ve had their confidence for forty years.”

For a day or two all went well. No doubt the business, if properly managed, could easily flourish at Blaauwildebeestefontein. The natives were as thick inland as ants, and large groups often came from the Shanquan region on their way to the mining fields of The Rand. Besides, there was good business to be had with the Dutch farmers, especially in tobacco, which I thought could make a good export if only work were put into it. Money was also to be found in plenty, and we sold almost exclusively in cash, although credit was often asked for. I set to work with great enthusiasm, and within a week or two I had visited all the farms and dwellings. At first Japp praised my energy, because it gave him a good opportunity to sit inside and have a drink. But his praise soon subsided, for he began to fear that I might take his place. He was very curious to know whether I had met Colles in Durban, and what he had said. “I have a letter from Mackenzie himself,” he told me countless times, “in which he praises me to the very top. Without old Peter Japp the trading house wouldn’t do, you see.” As I had no desire to argue with the old rascal, I just listened in silence to his talk. But that did not allay his fears, and he soon became so jealous that I began to feel very uncomfortable. He had been born in the colonies, and he never failed to press it. He was pleased with my incompetence in business matters, and if I ever made a mistake he would nag me about it for hours. “Well, Mr. Crawfurd, that’s no use at all; you English young men think yourselves very clever, but after all, we old men from the South are sometimes a little better. “In fifty years you may have learned a little, but we know everything before we start.” He roared with laughter when he saw me tie the roll, and he had a great deal of fun at my expense (and not without reason) when he saw me try to take care of the horse. I kept my composure very well, though sometimes I felt like completely softening Mr. Japp.

In fact, he was a dirty old rascal, — you could tell best from the way he treated Zeeta. The poor child worked all day in the house and probably did the work of two servants. He was fatherless and motherless, came here from some mission station. In Japp’s opinion he was a creature without human rights. He couldn’t speak to the girl without cursing at the same time, and he often hit and shoved her so that my blood boiled. And then one day he went too far. Zeeta had accidentally spilled half a glass of whiskey on Japp while cleaning. The latter got hold of some kind of whip, with which he began to beat Zeeta mercilessly, until the girl’s screams called me to the spot. I snatched the whip from the old man’s hand, grabbed him by the collar and threw him into a corner on the potato sacks, where he remained on his outing, fuming with rage and venting his worst curses on me. Then I in turn gave him my opinion on the matter. I told him that if such a thing happened again I would immediately inform Colles in Durban, adding that before that he would receive a beating which he would never forget. After a while he apologized, but I could easily see that he had begun to hate me darkly.

There was another thing I had observed about Japp. He boasted of his ability to treat the natives, but in my opinion his methods were unworthy of a white man. Zeeta was cursed and beaten, but there were other Kaffirs whom he received with a grovelling kindness. One large black rascal in particular often strolled into the shop and was received by Japp as if he were a long-lost brother. They would talk for hours afterwards, and though I understood nothing at first, I could see that the white man was groveling before the black. Once when Japp was away from home, the black creature came into the shop as if it were his own,—but he got out of the yard sooner than he had come in. Afterwards Japp reproached me for my treatment. “Mwanga is a good friend of mine,” he said, “and will get us several good deals. I beg you to be polite to him from now on.” I replied dryly that I was going to throw Mwanga out, as well as anyone else who didn’t behave properly.

Japp’s association with the Kaffirs continued, and I began to suspect that he was secretly procuring liquor for them. At any rate, I had noticed a few intoxicated creatures on the road between the native lodges and Blaauwildebeestefontein, and I recognized a couple of them as friends of Japp’s. I spoke to Mr. Wardlaw about it, and he said, “I think that old rascal has some ugly secret that the blacks know, and that is why they have such power over him.” I was prepared to believe that my friend was right.

I gradually began to feel lonely, for Mr. Wardlaw was busy with his books, and I had little company from him. I therefore resolved to get myself a dog, and I bought one from a poor preacher who would have sold his soul for a drink. The dog was a large Boer hound, a mixture of mastiff and bulldog, and who knows what else. The colour was mostly red-breasted, and the hair on the back grew against the rest of the coat. Someone had told me, or perhaps I had read somewhere, that a dog with a back like this meant that it would not be frightened by anything, even a roaring lion. And it was for this reason that I took my eye on this dog. I gave him ten shillings and a pair of boots (which I got at the shop at the buy-in price), and the owner of the dog bade me farewell, warning me to beware of the dog’s nature. Colin—that was the name I gave my dog—began his stay with me by tearing my trousers and scaring Mr. Wardlaw into a tree. It took fourteen days of relentless struggle before I could get Colin to agree to me, and I still have the evidence of it on my left arm to this day. But then he became my faithful shadow, and woe to him who dared to raise his hand against Colin’s master. Japp explained that the dog was an evil spirit, and Colin returned the compliment with sincere disgust.

In Colin’s company I now began to spend some of my free time in exploring the mountain’s hiding places. I had brought a small shotgun with me, and I borrowed a Mauser rifle from the shop. I had a natural eye and a steady hand, and I soon became both a good shot with a shotgun and—I think—an unrivalled marksman with a rifle. On the slopes of the mountain range there were partridges and grouse, as well as a species of pheasant, and on the grassy plateau I met a species of bird resembling our grouse, which the Dutch called the “rorkaan.” But the best sport was still to hunt the dwarf deer in the thickets, where the hunter has very little or no advantage. Once a wounded dwarf deer threw me to the ground, and if it had not been for Colin I would have been seriously injured. Another time I brought down a beautiful leopard with one shot in a gorge near Letaba, shooting it just over Colin’s head from a ledge of rock. Its skin is now in front of the fireplace in the room where I write this. Colin’s best qualities, however, came to be known on one of the excursions I made on my holidays down to the plains. There we had nobler prey: wildebeest, hartebeest, impala, and once also noodoo, as the Dutch call them. At first I was quite useless, and I was embarrassed in front of Colin. But then I gradually learned the alertness required in the lowlands, learned to follow the tracks, judge the wind, and creep forward under the cover of the bushes. And as soon as the bullet had struck, Colin was on the thing with lightning speed. The dog had the speed of a greyhound and the strength of a bull terrier. I blessed the day on which the poor itinerant preacher had passed by.

Colin lay under my bed at night, and it is to his credit that I made an important observation. I noticed that I was being spied on incessantly. Perhaps it had been going on ever since I had arrived here, but I did not realize it until the third month after my arrival. One evening, as I went to bed, I saw the hair on the dog’s back stand up, and it kept barking restlessly at the window. I had been standing in the shade, and when I stepped out to look out, I saw a black figure disappearing behind the fence in the back yard. Perhaps this was only a small thing, but from now on I was on my guard. The next evening I tried to look again, but I saw nothing. The third evening, when I looked out, I caught a glimpse of a face, pressed right into the window pane. After this I closed the shutters of the window as it got dark, and moved my bed to another part of the room.

It was the same in the open air. As I walked along the road I suddenly felt that I was being spied on. If I was about to go into the bushes by the side of the road, I would hear a faint rustling sound, which told me that the spy had gone his way. Wherever I went—on the road, in the meadows of the plateau, or on the barren slopes of the mountains—everywhere it was the same. I had silent companions, who occasionally revealed themselves by the rustling of branches, and eyes that I could not see were constantly staring at me. It was only when I sank down on the plain that the spying ceased. This state of affairs irritated Colin to the utmost, and my walks with the dog were nothing but growls from him. In spite of my efforts to restrain him, he once ran into the bushes, from which I immediately heard a cry of pain. He had caught hold of someone’s leg, and when I went to the spot I saw blood in the grass.

Since I had come to Blaauwildebeestefontein, I had forgotten all the mysteries I had resolved to investigate, because of the excitement of my new life and the unpleasant quarrels I had with Japp. But this constant lurking brought them back to my mind. I was guarded because someone or some people considered me dangerous. My first suspicion was directed at Japp, but I immediately abandoned it. My presence in the shop might have been less agreeable to him, but not my wanderings in the neighborhood. I might have thought that he had arranged the spying in order to make me leave my place out of sheer annoyance, but I flattered myself that Japp must know me too well to hope that such a procedure would succeed.

What annoyed me was that I could not get my spies out. I had been to all the camps in the vicinity, and was on fairly good terms with all the chiefs. First, there was Mpefu, a dirty old rascal who had spent a good part of his life before the war in a Boer prison. He had a mission station in his district, and his people seemed clean and prosperous. Majinje was a female chief, a little girl whom no one was allowed to see. His village was a miserable place, and his tribe was getting smaller every year. Then there was Magata, up in the mountains further north. He was no enemy to me either, for he used to offer me some refreshment when I was hunting there,—once he had called together about a hundred of his men, and I saw a great fight with wild dogs. Sikitola, the most prominent of all the chiefs, lived a little further away on the plains. I knew him and his men less, but if the spies were his men, they must have spent most of their time quite far from their kraal. At Blaauwildebeestefontein itself, almost all the Kaffirs were Christians, quiet, clean people who tended their little gardens and certainly liked me better than Japp. One day I was about to go to Pietersdorp to consult with the natives’ representative there, but then I heard that the old man who knew the area was gone and his successor was a young man from Rhodesia who knew nothing. Otherwise the natives around Blaauwildebeestefontein were known for their peace and quiet, which is why they very rarely received official visits. Now and then we saw a couple of Zulu policemen riding past in pursuit of some minor criminal and the tax collector also came to collect the taxes on the huts, but otherwise we did not give the government much to do and they did not have to worry about us.

As I have already mentioned, I began to think again about everything that had happened before I came here, and the more I thought, the more agitated I became. I had a habit of amusing myself by remembering everything I knew.

First, of course, was His Excellency John Laputa, his appearance on Kirkcaple Beach, his conversation with Henriques about Blaauwildebeestefontein, and his strange behavior in Durban. Then came all that Colles had said, that this place was somehow “stale” and that no one wanted to stay here, either in the shop or in the school. Then came my conversation with Aitken at Lorenzo Marques, and his story of the great medicine man in these parts, to whom all the Kaffirs made a pilgrimage, and his suspicions of the discovery of diamonds here. Last and foremost in my meditations was this constant lurking about me. It was obvious that there was some secret here, and I suspected old Japp would know it. One day I was foolish enough to ask him about diamonds. He laughed contemptuously. “That’s the sign of an ignorant Englishman,” he said. “If you had ever been to Kimberley, you would know what the diamond country looks like. You might as well find ocean pearls here as diamonds. But go and search for me, you will find some garnets.”

I made careful inquiries of Aitken’s medicine man—this was done with the help of Mr. Wardlaw, who was now a master of the Kaffir language—but we learned nothing. The only thing he could gather was that the people of Sikitola knew some medicine for fever, and that Majinje, if he wanted to, could procure rain.

Finally, after much consideration, I wrote to Mr. Colles, and gave the letter, just in case, to a missionary who was going to Pietersdorp. In the letter I told him frankly what Aitken had said, and also spoke of the ambush. I said nothing about old Japp, for, as unworthy as he was, I did not want a man of that age to be out of place.

IV.

MY JOURNEY TO THE WINTER PASTURE.

A letter came from Colles, but addressed to Japp and not to me. As far as I could gather, the old man had once suggested setting up a side shop at a place on the plain called Umvelos, and the firm was now willing to carry out this plan. Japp was exceedingly pleased and let me read the letter. It contained not a word of the matter I had written about, but only a series of detailed instructions for the organisation of the side shop. I was to take a couple of masons with me, load two wagons with bricks and timber, and travel to Umvelos to be present when the shop was built. The fitting out of the shop and the appointment of a manager would have to be left for later. Japp was delighted, for, apart from getting me out of the way for a few weeks, it was evident that his superiors valued his advice. He boasted again that the firm could not do without him, and towards me he became somewhat more impudent, in his new overestimation of himself. But then he took a deep breath of joy.

I must confess that I was offended that the letter did not mention anything of real importance. But I soon realized that if Colles usually wrote about such things, he would write to me directly, and so I eagerly waited for the post. No letter, however, arrived, and I soon became so busy with my preparations for the journey that I forgot to think about the whole matter. From Pietersdorp I got bricks and other building materials, and two Dutch masons who took on the work. The place chosen was not far from the Sikitola kraal, so that I could easily get native labor. When I was thinking about business, it occurred to me to kill two birds with one stone. Among those farmers who stick to the old ways and customs, it is customary to drive the cattle from the highlands to the plains — which they call winter pasture — for winter feed. At this time of the year there is no need to fear floods, and the grass is thicker and more abundant in the lowlands than in the highlands. I learned that some large herds of cattle were to pass by on a certain day, and that their owners and their families would follow in wagons. I therefore had a sort of mobile trading post arranged, and with my two wagons I joined the caravan. I hoped to do good business by selling one good and two beautiful to the farmers both on the way and at Umvelos.

It was a bright morning when we set out from the mountains to the plain. I had a full day’s work at first to get the heavy carts down the terrible precipice that served as a road. We tied the wheels with chains and hung heavy weights behind them as brakes. Fortunately my drivers knew their trade, but one of the Boer carts slipped over the edge and it took ten men to pull it back.

Further on the road improved as it began to follow the edge of a gently rising ravine. I rode alongside my carts, and the weather was so divine that I was content with my mere existence. The sky was a bright blue, the air warm, yet faintly tinged with the freshness of winter, and a thousand fragrant breaths from the forests penetrated my nostrils. Variegated birds, called the Kaffir Queen, fluttered above the road. Below, the Little Labongo roared and roared, with its small rapids and falls. Its water was no longer that clear, transparent “spring of the Blue Wild Beast,” but became increasingly turbid the nearer it came to the fat lowlands.

The ox-carts travel slowly, and when we camped in the evening we still had half a day’s journey to Umvelos. A little before sunset I spent lounging and smoking with the Dutch. In the early days they had generally shunned me as a newcomer and were taciturn, but now I could speak their language fluently, and we soon became good friends. I remember we had an argument about a dark object in a tree about 500 yards away. I thought it was a vulture, but one of the Dutch insisted it was a baboon, whereupon the oldest in the party, a man named Coetzee, took his rifle and fired without even aiming. Something fell from a branch, and sure enough, when we went to the spot we found the baboon’s head pierced through. The old man now asked me: “Whose side are you going to take in the next war?” — to which I replied, laughing, “Your side.”

After supper, the spices of which were chiefly from my own store, we sat smoking and talking round the fire, while the women and children were well and peacefully in the covered wagons. The Boers were all gentle, sociable men, and when I had finally mixed up some Scotch punch as an antidote to the evening’s gloom, we became very good friends. They asked me how I was getting on with Japp. Old Coetzee saved me the trouble of answering, for he managed to say: “Skellum, Skellum!” (= rascal). I asked him what he had against Japp, but all I got out of him was that Japp was too good a friend to the natives. Japp must have given the old man a bad name at some time.

We talked about hunting, and I heard many adventures—of Limpopo, Meshonaland, Sabie, and Lebombo. Then we passed into politics, and I heard some fierce attacks on the new land tax. All these men were old residents of the place, and I began to suspect that through them I might learn something of importance. So I related to them, in a low voice, a story I had heard in Durban about a great medicine man, and asked them if they knew anything about it. But they shook their heads. The natives had given up magic and sorcery, and are more afraid of the missionary and the police than of a witch. Then they began to talk about the old days. But Coetzee, who was hard of hearing, interrupted the others and asked me to repeat my question.

“Yes,” he said, “I know, there is an evil spirit living in Rooirand.”

I gained nothing more from him than the fact that there must be a devil there. His grandfather and father had seen it, and he himself had heard it roar when he had been there hunting as a boy. He would say no more, but went to rest.