The adventures of Umslopooaas and Galaz

The story of the Zulu caravans

Letter

H. RIDER HAGGARD

Translated from English to Finnish

OEN [OE Nyman]

(Previous Part Published Under the Title “Black Hero”)

Helsinki, Publishing Company Kirja, 1922.

CONTENT:

I. Mopo goes in search of the Killer.

II. Mopo reveals himself.

III. The murder of the Boers.

IV. The war against the Halakaz.

V. Nada.

VI. Trial by fire.

VII. Lily’s surrender. VIII

. Umslopogaas finds out who she is.

IX. Nada’s arrival.

X. The women’s war.

XI. Zinita at the king’s.

XII. The last battle of the grey and black people.

XIII. Lily’s farewell.

XIV. The revenge of Mopo and his foster son.

XV. Mopo ends his story.

I.

A MOBILE GOES IN SEARCH OF THE KILLER.

Dingaan did not like Duguza, but moved back to Zululand, building a large city near Mahlabate, which he named “Umgugundhlovu,” or “elephant’s trumpet.” At the same time he ordered that the most beautiful girls in the country should be sought out as wives for him, and although many such were found, he demanded more and more. He had also heard that among the Halakazi tribe of Swaziland there was a wonderfully beautiful girl, named Lily Flower, whose skin was much lighter than ours, and Dingaan began to ardently desire that girl as his wife. He sent orders to the Halakazi chief to hand over the girl to him, but the messengers returned with the news that they had been ill-treated by the Halakazi, beaten and thrashed, and that the king’s demand had been met with gross insults.

The greeting of the Halakaz chief to Dingaan, the king of the Zulu, was as follows: The girl who is called Lily Flower is indeed wonderfully beautiful and still unmarried, for up to now no one has appeared who has taken her fancy, and her relatives love her so much that there is no question of forcing her to marry against her will. The chief also said that the Halakaz despise Dingaan and his Zulus, just as their fathers had despised and defied Chaka, that they spit at the name of Dingaan, and that none of their girls will be given to any Zulu dog as a wife.

The chief then had the girl brought before Dingaan’s envoys, who thought her truly beautiful, for they said that she was as slender as a reed, and that when she walked she resembled the supple swaying of a reed in the wind. Her hair waved in long curls down to her shoulders, her brown eyes were large and gentle like those of a deer, the smile on her lips reminded one of the clear, sparkling water, and when she spoke her voice was sweeter to hear than the sound of musical instruments. They also said that the girl had wanted to speak to them, but the chief had not permitted any conversation, but had ordered her to be taken to her relatives.

When Dingaan heard the story, he went wild like a lion in a net, and now he really wanted the girl for himself. However, he did not get the girl, although he was the most powerful man in the world. He ordered a large army to be assembled, which he was to send to the Swazi country to destroy the entire Halakazi tribe and take the girl prisoner. But when the matter was brought up in a great consultation, I, as the commander of the military forces, opposed the project, saying that the Halakazi tribe was large and powerful, and war against them would cause war against the Swazis as well. The Halakazi lived in large caves, which were almost impossible to conquer. The time was also not right to send an entire army to war for just one girl. Only two or three years had passed since Chaka’s death, and there were many enemies; the ranks of the warriors had been suspiciously thinned in many wars, and more than half of the entire army had fallen in the Limpopo swamps. Now we had to live in peace until the ranks were once more whole, for now our army was as weak as a little child, as a man starved to death. There was no lack of girls; let the king take as many as his heart desired, but let no war be started over this one.

I spoke my words boldly to the king’s face, which no one would have dared to do to Chaka, and my courage touched the others, so that they all supported me. They all knew very well that a war against the Swazis at that moment would have been a most foolish and unfortunate undertaking.

Dingaan listened with frowns, but he was not yet so firmly seated on the throne that he would have dared to ignore our statements. There were still many in the country who loved and respected the memory of Chaka and did not forget that Dingaan and Umhlangana had conspired to murder him. After Chaka was dead the people forgot how cruel and wicked he had been; he was remembered only as a great man who had gathered the Zulus into a mighty nation from an insignificant beginning, like a blacksmith who forges a shining spear from a bar of steel. The yoke had not been much lightened, even though another sat on the throne, for Dingaan killed as Chaka had killed, and Dingaan oppressed as Chaka had oppressed. Therefore Dingaan yielded to the demands of his advisers, and no army was sent against the Halakaz to fetch that girl named Lily Flower. But his desire to have the girl for himself was not quenched, and from then on he hated me with all his heart, for I had thwarted his hopes by my resistance.

Let me say here, although I did not know it at the time, that the girl named Lily Flower was none other than my daughter Nada. It often occurred to me that no one else could be as beautiful as Nada. But I knew for sure that Nada and her mother were dead, for the man who had brought the sad news had himself seen them, their bodies embracing each other, as if the same stab had killed them both. However, he was wrong. My wife Macropha had indeed been killed, but the girl who lay bleeding beside her was not Nada, but someone else. The tribe to which I had sent Macropha and Nada paid tribute to the Halakaz, and the chief of the Halakaz, who had usurped the place of the Wolf-Galaz, had quarreled with the above-mentioned tribe, upon whom he had then fled one night, destroying it completely.

Later I learned that the real cause of the quarrel and the expedition of destruction was none other than Nada’s beauty, which finally proved to be the ruin of the Halakazi as well. The rumor of her beauty had spread everywhere, and the old chief of the Halakazi had ordered that the girl be brought to live with him and to delight him and his surroundings with her beauty, and if he then saw fit, he would marry the girl to some noble Halakazi. But the demand was answered in the negative, for no one who has seen Nada the Lily Flower voluntarily gives up the pleasure of admiring her beauty, although the girl’s condition was such that no one wanted to force her to marry against her will. There were indeed many suitors both there and among the Halakazi, but she only shook her head and said: “No, I will not marry,” and that was all.

There was a sort of common agreement among the men, which at last became a proverb, that it was better for Nada to remain unmarried, so that they might all admire her, than to disappear from their sight into her husband’s hut; for her beauty was granted to be a delight to all, like the beauty of dawn and evening. Nada’s beauty, however, was the cause of much sorrow and weeping, as you will hear. Because of her beauty and grace, the lily itself had to wither and empty the cup of sorrow to the bottom; therefore the heart of Umslopogaas’ son Chaka became desolate and empty like a plain destroyed by the dawn of a fire. Thus it was permitted, my father, and so it was. All men, both white and black, are always seeking that which is beautiful, and when they finally find it, it suddenly disappears or perhaps brings death to them. Joy and beauty have wings, and they do not stay long on earth. They appear suddenly like an eagle from a cloud and disappear just as quickly.

Then I began to suspect a little, my father, that my daughter Nada, whom I had thought dead, was indeed the very girl named Lily Flower, who lived with the Halakaz, and whom King Dingaan wanted to have as his wife.

Having thus thwarted his plan to send an army to pluck the Lily from the garden of the Halakaz, he began to hate me. I also knew his secret, for we had killed Chaka and Umhlangana together, and I had saved Panda when he was about to murder her too, so that he hated me for all that, as little souls often hate those who have helped them forward. He did not wish to harm me, however, for my voice echoed over the whole land, and the people listened when I spoke. He began to look for some excuse to get rid of me for a while, until he had become powerful enough to dare to kill me.

“Mopo,” he said to me one day as I sat before him among his advisers and warlords, “do you remember the last words of the great elephant?” He meant his brother Chaka, though he did not mention his name, for Chaka was now considered sacred in the land, a hlonipa —like all dead kings—whose name it was against the law to mention.

“I remember, O king,” I answered. “Strange words indeed, for they contained a strange prophecy. The throne of kings will not long be yours and your house’s; white men will usurp your kingdom and divide your lands. So the lion of the Zulus prophesied when he died; what is the use of speaking of it? I have heard him prophesy once before, and his words came true. May that prophecy be like an empty egg that will never be hatched, and may its mother never nest on your roof, O king.”

Dingaan trembled with fear, for Chaka’s words troubled him day and night; then he became cruel and roared, biting his lip:

“You fool! Can’t you hear a raven cawing on the roof of some hut without going to tell those inside that it’s waiting to peck their eyes out? Birds of such ill-omen can do very badly, Mopo!” He looked at me menacingly and continued: “I didn’t mean those words that came out of a death-clouded brain by chance, but those that were spoken by a chief named Bulalio, who rules the axe-people tribe far to the north in the shadow of Ghost Mountain. I must have heard the words while sitting in the shade of the reed fence, before I could come to my brother’s aid against that Masilo, whose spear struck the king to death.”

“I remember those words, O king,” said I. “Does the king wish that warriors be sent to discipline that stubborn man? In his last moments one who is dead gave such an order.”

“No, Mopo, I do not want that. Since there was no army to send to destroy the Halakazi and to retrieve one whom I longed for, the joy of my eyes, there will certainly not be found now the warriors needed to destroy that Slayer and his tribe. Moreover, this Bulalio has not offended me, but an elephant whose trumpets have fallen silent. Now I want you, my Mopo servant, to go with just a few warriors to that Bulalio in a friendly manner and say to him: ‘The elephant whose footsteps now tremble the earth is greater than the one who has fallen into the lap of sleep, and his ears have heard that you, the chief of the axe people, do not pay any tribute. You have also said that you do not care one bit about him whose shadow darkens the earth, for the sake of a Mopo. A Mopo has now come to you, Slayer, to hear if there is any truth in the story, for if so, you will soon have feel how crushingly heavy the foot of the trumpeting elephant in Umgugundhlovu is. Think and weigh your words carefully before you answer, Killer!'”

I heard the king’s order, which did not give me much reason to think, for I knew very well that he only wanted to get rid of me for a while, so that he could plot my downfall in peace, and that he did not really care a bit about that insignificant chief living far away who had dared to defy Chaka. I was willing to go, however, for I had a burning desire to see that Bulalio, who had said he would avenge the death of a certain Mopo, and whose exploits were such as Umslopogaas would have done if he had lived. Therefore I answered:

“I have heard your command, O king. Your command will be fulfilled, even if you send a great man for a small matter, O king.”

“Not at all, Mopo,” replied Dingaan. “I feel in my heart that that young cock will grow into a fearsomely large cock if his wattle is not cut off in time, and you, Mopo, know how to cut wattles, even larger ones.”

“I heard your command, O king,” I replied again.

Having selected ten trustworthy men with me, I, Mopo, set out the next morning to journey towards the Ghost Mountain, remembering as I walked the journey I had made long ago along that same road. At that time, my wife Macropha, my daughter Nada, and Umslopogaas Chaka’s son, who was thought to be my son, walked beside me. Now they were all dead, as I thought, and I was journeying alone—to die soon myself. In those days, people did not live long, but so what. After all, I had avenged Chaka and satisfied my heart.

At last we arrived one evening in that lonely region where we had once spent the night on that night of sorrow when Umslopogaas fell prey to a lioness; I went to see the cave where she had found the cubs, and caught a glimpse of the hideous face of the stone sorceress who sat eternally above. I was so distressed that I could not sleep, but sat awake all night, gazing in the bright moonlight at the fierce features of that stone image and the dark forest that reached to my knees, wondering to myself if that forest could possibly hide the crushed bones of Umslopogaas.

Along the way I had been told many stories about that Haunted Mountain, on whose slopes everyone said that ghosts roamed in the form of wolves, and others had heard that there were ghosts there like men, esemkofu —dead people who had been brought back to life by witchcraft. These esemkofu were speechless, for otherwise they would have cried out to all mortals the terrible secrets of death, which is why they could only cry and wail like little children. In the darkness of the silent trees of the forests one could certainly hear their plaintive moans at night: “Ai—ah! Ai—ah!”

You laugh, my father, but I did not laugh when I remembered all those stories; if a man has an immortal soul, where does that soul go after the body dies? It must go somewhere, and would it be so strange that it returns to see its native land? I have never troubled my head with such things, though I am a doctor and know a thing or two about the ghostly people, the amatongo . To tell the truth, I have seen so many deaths and been an assistant in so many, that the dead have never been able to arouse any greater interest in me; then I will see everything when I myself enter their midst.

I sat and looked at the mountain and the forest growing on its slopes, and suddenly I heard a faint sound in the distance, which seemed to come from the very heart of that forest. The sound was at first faint, like a child’s cry heard in the distance, but it grew louder and louder, without my being able to say what it was; now it drew nearer, and at the same time it became clear—it was the howling of wild beasts chasing some game.

The echo echoed from one hillside to the other and my heart pounded. That herd, howling in the silent night, could not be small, now it was already on the other side of the village, and the brawl grew so loud that even my companions woke up from their sleep and looked around.

At the same time a plump koodoo bull appeared, which stopped for a moment on the hilltop, clearly visible against the sky, and then disappeared into the shadow below. To judge by everything, the animal rushed towards us, and after a moment we saw it galloping forward with long leaps. This we saw also—on the hilltop appeared a countless crowd of gray and thin creatures, rushing forward as quickly as the spirits of a hornet, disappearing into the shadow, reappearing in the moonlight, and disappearing again into the darkness of the valley, and behind the herd ran two other creatures—two men.

The bull passed us by scarcely half a spear-throw, and behind it rushed a vast pack of great wolves, from whose mouths came that terrible howl. But who were those two stout and sinewy-looking human-like creatures who hunted with the wolves? They ran swiftly and silently, with wolf teeth gleaming on their foreheads, and wolf fur flapping on their shoulders. One had an axe in his hand—the blade gleaming in the moonlight—and the other a heavy club. I have never seen anyone run so fast. Look, they were rushing down the slope towards us, the wolves left behind except four; we heard the thud of feet: they came, rushed past, and disappeared from our sight, the pack in their wake. The howling grew fainter as the hunt progressed, and at last faded into inaudibility; around us again reigned the deep peace of the still night.

“Well, comrades,” I said to my companions, “what was this vision?”

Someone answered: “We have seen the ghosts that lurk in the bosom of that old witch, and the Wolf-men, those witches—the kings of ghosts!”

II.

THE MOPED EXPRESSES ITSELF.

We watched all night, but we saw no more of the wolves or the men with them. At daybreak I sent word to Bulalio, the chief of the axe people, that a messenger from King Dingaan was coming to him, and wished to speak to him peacefully in his hut. I told the messenger that he must not give my name, but must only call me “Dingaan’s Mouth.” Then I set out with my men, for there was still a long way to go, and the messenger had been ordered to return at once to meet me, to learn what the Slayer, the owner of the slayer, had said.

We wandered until sunset, following the river that flowed at the foot of Ghost Mountain. We met no one, but once we came upon a ruined village, littered with crushed human bones, rusty spears, and the remains of black and white spotted oxhide shields. I examined them and concluded from the colors that they had belonged to warriors whom Chaka had sent years ago to search for Umslopogaas, but who had never returned.

“It must have been bad for those warriors of the Elephant-dead,” I said, “for I certainly think these shields were theirs, and with their eyes they looked at the world from the empty sockets of those skulls.”

“These are their shields and those are surely their skulls,” said someone. “Son of Mopo Makedama, this is not the work of human hands. Men do not crush the bones of their enemies as these have been crushed. Wow! not men, but wolves! And last night we saw wolves hunting, and they did not hunt alone, Mopo! Wow! This land is a haunt of ghosts!”

We continued our journey in silence, and the face of the stone sorceress who sat on the top of that mountain stared at us all the time. At last we reached an open plain and saw on the other side of the river a village of the Axe People, perched on a hill. The village was large and well built, and I could not count the number of cattle roaming the plain. We crossed the river at the ford, and then waited until we saw the man I had sent hurrying towards us. He greeted me, and I asked him what was happening.

“This I can tell you, O Mopo,” replied the man: “I have seen him whose name is Bulalio—he is a big man, tall and sinewy; his face is fierce, and he always carries a formidable spear in his hand—like the one we saw last night. When I was brought before him, I greeted him and spoke the words you dictated to me. He listened, and then burst out laughing, saying: ‘Take my greetings to him who sent you, that the ‘mouth of the ingane’ is welcome and may safely present the case of Dingaan. I would rather see it be Dingaan’s head that comes, and not just the mouth, for then the Weeper would also interfere in the conversation—for a certain Mopo who was murdered by his brother Chaka. The Weeper might have something to say to Dingaan too! But the mouth is not the head, so let the mouth come in peace.'”

I was startled to hear that Mopo’s name had once again been on Bulalio’s lips. Was there anyone else who had loved Mopo so tenderly, except one who had died long ago? Perhaps Bulalio was talking about another Mopo, for I was not the only one of that name—in his great mourning party Chaka had indeed murdered a chief of the same name because—as he said—there was no need for two Mopos in the country, although that other Mopo was still weeping profusely when the eyes of the others had already dried up. I only told my men that Bulalio had guts, and so we entered the village gate. There was no one there to receive us, and the huts inside looked deserted, but further on from the cattle-pen in the middle of the village there was dust rising and a noise as if a group of men were going to war. Some of my men were frightened, thinking they had fallen into some trap, and wanted to turn back, but then they were only frightened when, as we came to the gate of the cattle pen, we saw five hundred men in arms, company by company, commanded by two burly men in front of the lines, bustling and shouting commands.

But I cried out: “No, no! Do not flee! A bold appearance discourages the enemy. And if that Bulalio had wanted to kill us, he would not have had to gather such a large army. He is proud and wants to show his power, not knowing that the king we serve has a company for every one of his warriors. Let us only come forward boldly!”

So we continued our journey towards the group standing at the other end of the enclosure. We were noticed at once, and those men who were practicing their warlike skills came towards us, walking one after the other. The one in front had a spear on his shoulder, and the other was swinging a large club. I looked at the bearer of the spear, and, my father, joy seized my heart, for I knew him, although it had been years since I last saw him.

Umslopogaas it was—my foster-bred Umslopogaas and no other!—he was now a man in his prime, a man like no other in all Zululand. He was stout and strong-looking, a little thin in the upper body, but his shoulders were broad and his chest well arched. His arms were long and moderately thick, but the muscles that stretched the skin were like knots of rope; his legs were also long and very thick at the calves. His eyes were eagle-like, his nose slightly hooked, and he held his head slightly forward, like a man who is always stalking some hidden enemy. He seemed to walk comparatively slowly, but he was approaching surprisingly quickly, his step was strangely gliding, reminiscent of a wolf or a lion, and the fingers that held the Weeper’s horned arm were constantly moving. His companion was half a head shorter than him, a stocky man too, but more solidly built than Umslopogaas. His eyes were small and twinkled incessantly like little stars, and his face was very fierce, especially when he grimaced this way and that, so that his white teeth shone.

When I saw Umslopogaas, I was overjoyed to rush to embrace him, but I restrained myself, for the moment was inopportune, and to prevent him from recognizing me, I drew the hem of my cloak over my face. At that moment he stood before me, examining me with his sharp gaze, and I went up to greet him.

“Hail to you, mouth of Dingaan!” he said in a resounding voice. “You are small for the mouth of so great a chief.”

“Even the body of a great king has its mouths filled with smaller parts, O Chief Bulalio, ruler of the axe people, king of the wolves of Ghost Mountain, who was called Umslopogaas in ancient times, son of Mopo, son of Makedama.”

Hearing the words, Umslopogaas started like a child afraid of noises in the night and stared at me without blinking.

“You know a lot of things,” he said.

“The king’s ears are long, though his mouth is small, O Chief

Bulalio,” I replied.

“How do you know I’m with the wolves of Haunted Mountain, oh mouth?” he asked.

“The eyes of the king see far, O Chief Bulalio. Last night they saw a hunt that was both terrifying and beautiful. A great koodoo bull came running for its life, followed by a countless pack of howling wolves, and two men just like you, wearing wolf skins.”

Umslopogaas raised his dagger as if he intended to crush my head, but then let his weapon fall, while Wolf-Galaz stared at us with wide eyes.

“How do you know that my name was once Umslopogaas, which I have almost forgotten myself? Speak, O Mouth, or I will kill you!”

“Do as you wish, Umslopogaas,” I replied, “but also know that when the brain is rotten, the mouth is mute. Destroying the brain is destroying information.”

“Answer!” he said.

“No. I’m not obligated to do that. I know your biography and that’s fine. Now to my business.”

“I don’t like to be rude in my own territory,” Umslopogaas would snarl, gritting his teeth; “say your piece quickly, you foul-mouthed one!”

“This is my business, little chief: When the great Elephant was yet alive, you sent him greetings through one Masilo—greetings the like of which his ears had never heard, and which would have been your death, you pride-swept fool, had not death at once corrected the great Elephant. Now King Dingaan, whom I serve, and whose shadow now darkens the land, wishes to speak to you through me. He wishes to know whether it is true that you do not acknowledge his supremacy, and do not intend to hand over to him warriors, girls, and cattle as tribute and to aid him in the war? Answer, chief—answer briefly and to the point!”

Umslopogaas was panting with rage and fingering his axe handle angrily. “Thank your luck, O Mouth,” he finally snarled, “that I promised not to touch you, or else you would not have gotten out of here—you would have been like some warriors long ago who came looking for a certain Umslopogaas. I will answer you briefly and to the point. Look at those spears—they are only a quarter of the total number of my troops—that is my answer. Do you see that mountain, that den of wolves and ghosts—no one knows it and no one can enter it but me and one other—that is my answer. The spears and the mountain unite—the spears and the fangs of the wolves bring the mountain to life. Let Dingaan take his tribute from there! I have spoken!”

I laughed sarcastically to test even more the patience of Umslopogaas, my foster-child.

“You fool!” said I; “a boy with the brains of a monkey. Dingaan, whom I serve, can send a hundred for each of your spears; your mountains will be trampled to the ground, and your wolves and ghosts—with Dingaan’s mouth I will spit them in the eyes!” And I spat on the ground.

Umslopogaas was so furious that even the slayer shook. “Hey, Wolf-Galazi!” he growled to the man standing behind him, “shall we kill him and his companions too?”

“No,” replied Galazi, grimacing, “you promised them peace. Let them return to their king-dog, so that he may then send his puppets to fight with our wolves. That is worth watching!”

“Go, O Mouth,” said Umslopogaas, “take heed, lest any misfortune befall you! Outside my gates you will find food to satisfy your hunger. Eat first, and then set off quickly for your home, for if you are found within a spear’s throw of my village at noon tomorrow, you and your companions will remain there forever, O Mouth of King Dingaan!”

I moved as if to leave, but suddenly turned back and said:

“In your greetings to the great Elephant, you spoke of a man—what was his name now—yes, a certain Mopo?”

Umslopogaas started as if stabbed by a spear and stared at me.

“About Mopo! What do you know about Mopo, O Mouth whose eyes are covered?

Mopo is dead—I am his son!”

“That’s right!” I said. “Yes, Mopo is dead—the great Elephant-dead killed a Mopo. How is it to be understood that you, Bulalio, are his son?”

“He is dead,” repeated Umslopogaas, “he and all his house! That is why I hated the great Elephant, and that is why I hate Dingaan, his brother, and may I be as unfortunate as Mopon before I give him even an ox as tribute.”

Up until now I had changed my voice, but now I said it in my normal voice:

“Oh! Those words came straight from your heart, young man, and now I have found out where the evil lies. So you defy the king because of that dead Mopo dog?”

Umslopogaas heard the sound and his anger turned to fear and astonishment. He looked at me searchingly, but said nothing.

“Have you any hut near here, O Chief Bulalio, you enemy of Dingaan, where I, the Mouth of King, can speak with you for a moment alone, to learn your answer word for word, so that I may deliver it to you in its original form. Do not fear, Slayer, to be alone with me in an empty hut! I am old and unarmed, and you have in your hand a weapon that I fear,” and I pointed to the slayer.

“Follow me, O Suu, and you, Galazi, stay with these men,” replied Umslopogaas, starting to walk ahead.

Soon we came to a large hut. He pointed to the doorway, and I crawled in, him following behind me. It was dark inside, for the sun was already beginning to set, so I waited until our eyes adjusted. Then I suddenly threw the cloak from my face and looked Umslopogaas in the eyes.

“Look at me now, O Chief Bulalio, once called Umslopogaas—look at me and tell me who I am?” He looked and his mouth opened in astonishment.

“You are my father Mopo in his old age—Mopo who is dead, or rather Mopo’s spirit,” he replied in a low voice.

“I am your father Mopo, Umslopogaas,” I said. “It took you a long time to recognize me, though I recognized you at once.”

Umslopogaas calmed the Weeping Man, and threw himself into my arms, bursting into tears. I cried too.

“Oh, my father!” she sobbed. “I thought you had died with the others, and now you have come back to me, and I was about to raise my sword against you in my madness. It is good that I have lived—to live to see once more your face, which I thought I would never see again. It has changed greatly—has age and sorrow left their mark on it?”

“Yes, my Umslopogaas child. I thought you were dead too. I thought that lion had killed you, though to tell the truth it seemed very strange to me that anyone but you, Umslopogaas, could have performed the feats that Bulalio, the chief of the axe people, was said to have done—to defy Chaka to his face. But you are not dead, and neither am I—the Mopo that Chaka killed was another of the same name; I killed Chaka and not vice versa!”

“And where is my sister Nada? Oh, tell me quickly!” Umslopogaas asked frantically.

“Your mother Macropha and your sister Nada are dead, Umslopogaas.

They were killed by the Halakazis living in Swaziland.”

“I have heard of that tribe,” he said, “and so has Galazi. He has sworn vengeance upon them—they killed his father, and so now I swear vengeance upon them, for they have slain my mother and my sister. O my sister Nada, O my sister Nada!” and the great man covered his face with his hands and rocked his body in his inconsolable grief.

I already thought of telling Umslopogaas the truth and telling him that Nada was not his sister and he was not my son, but Chaka, whom I had killed. I said nothing, however, although I now wish I had. For I saw how proud and ambitious Umslopogaas was. If he had known that the throne of Zululand was really his, nothing could have restrained him from rising before long in open rebellion against King Dingaan, for which I did not think the time was yet suitable. If I had known a year before that Umslopogaas was still alive, he would have been sitting today on the seat on which Dingaan now sat, but I did not know, and the opportunity had passed for the time being. Dingaan was now king to muster many regiments, for I had opposed all wars, as when there was talk of an expedition against the Swazis. The opportunity had passed, but it might come again, and until then I must keep quiet. I thought it best to first get Umslopogaas to join Dingaan, so that he might gain a great and lasting reputation throughout the land as a mighty chief and the foremost of warriors. Then I would see to it that he should be promoted to the position of advisor and finally to the position of chief of the army, for the chief of the army is already half a king.

So I said nothing about it, but we sat and talked until daybreak, telling each other all that had happened since the lion had robbed him of me. I told him how all my wives and children had been murdered, how I had been tortured, and I showed him my withered hand. I also told him about the death of my sister Baleka and the whole Langen tribe, and how I had avenged all the wrongs I had suffered on Chaka and raised Dingaan to the throne, being now myself the first man in the kingdom after the king, although the king was very afraid of me. But I did not tell him that my sister Baleka was his own mother.

When I had finished my story, Umslopogaas told his own! how Galazi had saved him from the lion’s teeth, and how he became another Wolf-Wolf; of the match in which he defeated Jikiza and his sons, thus becoming the chief of the axe people and taking Zinita as his wife, and how he had then become a mighty man.

I asked him why he was still hunting with the wolves, as he had done last night. He replied that now that he was a great man and had nothing more to gain, he got tired of everything from time to time, and he had to go for a walk with Galaz and the wolves, because it only gave him pleasure and relieved his nagging longing.

I said I would put him on the trail of a better beast before long, and then asked him if he loved his wife Zinita. Umslopogaas replied that he would love Zinita much more if she loved him a little less, for Zinita was jealous and quick-tempered, causing him much trouble. After we had slept a little, he took me out, and my men and I were now entertained most excellently, and I talked to Zinita and Wolf-Galaz. I liked the man at first sight. Such a comrade was good to have by my side in the fury of battle, but I felt a great dislike to Zinita. He was beautiful and well-built, but the look in his black eyes was fierce and piercing, and he would not leave my foster-son in peace for a moment; he, who feared nothing under the sun, seemed to be afraid of Zinita. And Zinita did not like me either; Seeing how Umsiopogaas tried in every way to please me, he immediately became jealous — Galazi was already used to it — and wanted to get rid of me as soon as possible.

I didn’t like him and in my heart I sensed that he would do a lot of harm, which my fear came true in full.

III.

THE MURDER OF THE BOERS.

In the morning I took Umslopogaas aside and said: “My son, yesterday when you thought I was only Dingaan’s mouthpiece, you gave me various greetings to take to King Dingaan—greetings that would certainly have brought death to you and your people if they had reached the king’s ears. The lonely tree in the desert thinks itself very great, Umslopogaas, and thinks that the shade it creates is unparalleled. But there are other trees that are even greater. You, for example, are such a lonely tree, but the top branches of the tree I serve are thicker than your trunk, and in its shade dwell many woodcutters who are sent to cut down other trees that are trying to grow too tall. You cannot compare your strength with Dingaan, although living alone in this distant land you are a very great and mighty man in your own eyes and in the eyes of those around you. Bear this in mind, Umslopogaas: Dingaan hates you for those greetings that you give him. “You sent that Masilo hawk with you to the great Elephant, and he intends to destroy you. He sent me on this journey only to get away from me for a while, and it really doesn’t matter what answer I bring him — the day when you see his warriors swarming before your gates will surely dawn.”

“What will this matter be improved by talking about?” asked Umslopogaas. “What is meant to come, will come. I will wait here for Dingaan to come and fight until I die.”

“Not so, my son Umslopogaas, not so; a man dies in other ways than by being stabbed with a spear, and a crooked staff can still be straightened in the steam. I would hope that Dingaan’s hatred for you would turn into love and that you would prosper in his shadow—achieve fame and power. Listen! Dingaan is not Chaka’s equal, though he is as cruel as Chaka. Dingaan is a tempter, and it may well happen that some man who has risen in his shadow will eventually overshadow him. I could do it any time—yes, I myself, but I am already too old and burdened with sorrow to wish to rule. But you are young, Umslopogaas, and there is no other like you in the land. There are other more important reasons of which I cannot yet speak, but which always give you new strength.”

Umslopogaas looked at me searchingly, for then he was ambitious and always wanted to be first. And could it be otherwise, with Chaka’s blood flowing in his veins?

“What is your plan, my father,” he asked. “How do you intend to accomplish all this?”

“There are many ways, Umslopogaas. In the Halakazi tribe, living in Swaziland, there lives a girl named Lily Flower, who is said to be incomparably beautiful, and whom Dingaan ardently desires to marry. A short time ago, Dingaan sent an embassy to the Halakazi chief to ask for the girl as a wife for the king, but the Halakazi chief replied very insultingly that the world’s beauty would not be given to any Zulu dog. Dingaan became cruel and would have sent an army to destroy the entire Halakazi tribe, but I fought back, saying that now was not a suitable time for war; therefore Dingaan hates me; he has sworn to pick that Swazi lily. Do you understand what I mean, Umslopogaas?”

“Somehow. But you can speak openly.”

“Wow! Umslopogaas. In this country, half words are better than whole words. So listen! This is how I have decided the matter: you will run against the Halakaz tribe and destroy it and bring the girl to Dingaan as a sign of reconciliation and friendship.”

“A good plan, anyway. I’ll try to get the girl, but I don’t care if I don’t succeed; at least we get to fight and share the spoils after the battle.”

“Win first and then worry about the loot, Umslopogaas.”

He thought for a moment and then said, “Allow me to order Galazi here.

He is a trustworthy and quiet man, so don’t be afraid.”

Galazi came immediately, and I explained to him that Umslopogaas intended to attack the Halakazi and take the girl he longed for as a gift and appeasement to Dingaan, which plan, however, I thought was very dangerous, since the Halakazi tribe was known to be large and powerful. By speaking in this way I reserved a back door for myself in case Galazi should betray us, which intention Umslopogaas also noticed, but my caution was unnecessary, for Galazi was trustworthy.

He listened in silence until I had finished, and then said calmly, although it seemed to me that his eyes were flashing:

“Yes, by right I am the chief of the Halakaz, O Mouth of Dingaan, and I know them well. The tribe is large and can field two full regiments, while this Bulali has only one at his disposal, and that too a small one. They have, moreover, guards outside day and night, and the country is full of spies, so that surprise is hardly possible; their main fortification is also a stronger than usual, a large cave, open in the middle, which no one has yet been able to conquer and the entrance to which is known to few. I am one, for my father showed it to me when I was a boy. So you understand that this expedition against the Halakaz, which Umslopogaas is planning, is not such a small matter. With the Bulali it is as I have said, but with me it is different, O Mouth of Dingaan. Years ago I swore to my dying father, who had been poisoned by a daughter of that tribe, a witch, that I would avenge his death. and I will not rest until I have destroyed the whole tribe, killed the men, dragged the women to foreign lands and the children into slavery! Living alone on the slopes of Ghost Mountain, I have thought for years, months and nights about a way to fulfill my oath, but I have come up with nothing. Now the opportunity has finally come, and I am glad. Our intention is indeed dangerous, fulfilling it could sweep the entire axe people into nonexistence.” He fell silent and took a pinch of snuff, eyeing us over the box.

“However, as far as I am concerned, the situation is different from what you seem to think, Wolf-Galazi,” said Umslopogaas. “Those Halakazi dogs killed your father and mother, but they have also killed, as I learned only yesterday, my mother and my sister Nada, whom I loved more than anything in the world and who also loved me. That man, the Mouth of Dingaan,” he pointed to me, “says that I will gain Dingaan’s favor if I can destroy the Halakazi and capture that girl named Lily Flower. Not that I care for Dingaan. I will go my own way, live as long as I live and die when my time comes, but to avenge the death of my mother and my dear sister I will conquer and destroy those Halakazi or perish myself. Perhaps you will see me soon, O Mouth of Dingaan, at the king’s in Mahalabatin, with the Lily Girl and the herd of Halakazi with me. If not, then you will know that I have fallen with my warriors.”

In Galazi’s presence Umslopogaas spoke thus, but when we were alone he embraced me and said a tender farewell, for the hope of a reunion was small. But it often happens that the brave triumph. Then we parted—I to return to Dingaan to tell him that Bulalio, the chief of the axe people, had gone against the Halakaz to bring the girl named Lilja as a peace offering to the king, while Umslopogaas remained to prepare for war.

I hurried back from the Ghost Mountain to Umgugundhlovu and went straight to Dingaan, who at first looked at me very narrowly. But his manner changed as soon as I told him my greetings and how the Bulalio chief had set out on the warpath to win the Lily girl for the king. He thanked me well, holding my hand, and said he had been foolish to doubt me when I had done my best to dissuade him from the war against the Halakaz. Now he saw that my intention had been to light that fire with my other hand and save his hand from being burned.

He also said that if the chief of the axe people would bring him the girl, he would forgive the greetings sent to the great Elephant. He promised to give even the cattle plundered from the Halakaze as a reward to Bulalio and to make him a great man. I replied that all would be as the king wished. I had only done my duty by acting so that a proud chief was humbled and an enemy was defeated—without the king having to lose anything. It might even be so good that Lily Flower would soon be with the king.

Then I waited for the development of events.

Now, my father, the white men, whom we call Amaboon and you call Boers, are also beginning to appear in connection with my story. Oh! I think nothing good of those Amaboons, although it was I who helped them defeat Dingaan—I and Umslopogaas.

A few white men had indeed come to Chaka and Dingaan from time to time, but they mostly, with the exception of a few hunters, came only to pray and not to fight. These Boers, on the other hand, pray and fight and steal, which I cannot understand at all, when your own worshippers declare such a thing to be a sin.

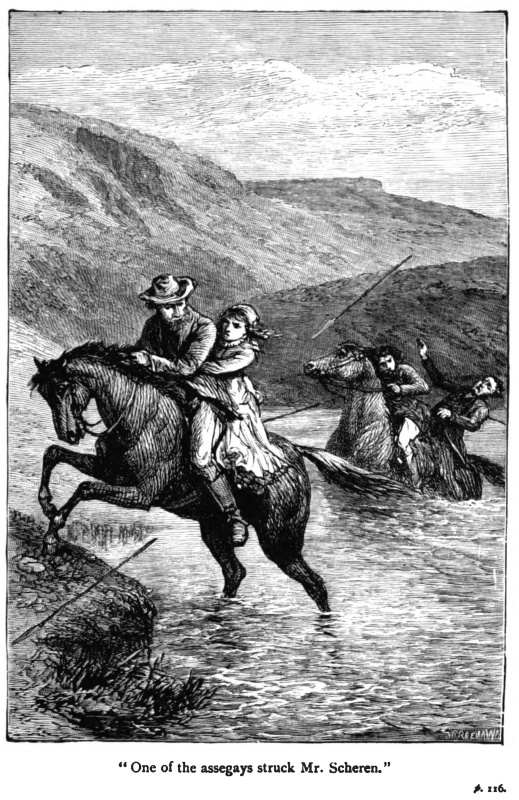

Well, after I had been at home for a month after my journey, there came to Dingaan about sixty Boers, led by a great man named Retief, armed with snares —I mean those long guns which the Boers had at that time—or perhaps a hundred in all, including servants and assistants. Their purpose was to purchase a tract of land in Natal between the Tugela and Umzimoubu rivers. But at the instigation of myself and other advisers, Dingaan made a pact with them that they would first attack a chief named Sigomyela, who had stolen the king’s cattle, and bring back the cattle. The Boers agreed, and it was not long before they returned, driving Sigomyela and the cattle stolen from the king before them.

Dingaan’s face lit up when he saw the spoils, and that very evening he called a great council, the amakapat , to consider the question of the cession of the land. I said at once that it made no difference whether he agreed or not, for the great Elephant had already given the land to the English, the children of King George. Whatever Dingaan did, it would eventually happen that the English and the Amaboonas would fight for the possession of the land. The prophecy of the great Elephant was beginning to come true, for now we could hear the sound of rushing footsteps as the white people approached, who were to invade our kingdom.

Dingaan’s face darkened, for my words had wounded him like a barbed spear, and he ended the meeting without answering anything.

The next morning the king promised to sign the treaty of surrender, which guaranteed the Boers the right of possession of the territory they had asked for, and all was as peaceful as a calm lake. But before the paper was signed, the king gave a great dance, which lasted three days, for the city was overflowing with soldiers, but on the third day the regiments were ordered to leave, except one, composed of young men, who were ordered to stay. I wondered all the time what Dingaan could possibly have in mind, and I feared for the strangers. The regiment had received secret orders, of which not a word was revealed to anyone—not even to me. I knew he was brooding over evil, and I was already going to speak of it to Captain Retief, which I did not do, however, for fear of being ridiculed. Ah, my father, how many would have been saved if I had spoken! But what of that! In any case, only a few of them would be alive. Early on the morning of the fourth day, Dingaan sent word to the Boers, asking them to come to the cattle-pen, where the paper was to be signed. And the Boers came, leaving their guns at the gate, for no one, whether white or black, was allowed to come armed before the king under pain of death. Umgugundhlovu was built, as royal cities usually are, in the shape of a large circle, and its many thousands of huts were placed in three rows between a high inner enclosure, within which a large open field could have accommodated five regiments at once. The cattle-pen, separated by an arched enclosure, was at the other end of the field opposite the gate, and behind it were the emposeni , the residence of the king’s wives, and the store-rooms and the intunkulu , the king’s residence. A seat was reserved for the king in front of the cattle-pen, on which Dingaan sat down as soon as he arrived, and a servant held a shield over him so that the sun would not bother him. We, the advisers, were also present, and the regiment, which had been ordered to remain, was drawn up in line on two sides. The warriors had only short sticks—no clubs, my father—and the chief stood near Dingaan on the right.

The Boers came on foot and entered in a group before the king, who greeted them kindly, even extending his hand to Captain Retief. Then Retief took from a leather case a treaty in which the boundaries of the territory were precisely determined, and which an interpreter translated for the king. Dingaan said that everything was as it should be and drew his wooden sign on the edge of the paper, and Retief and the Boers were very happy. They would have liked to say goodbye at the same time, but Dingaan asked them to stay, saying that first they must eat and watch the warriors dance for a while. He ordered boiled meat and milk to be brought for the guests, but the Boers said that they had already eaten. However, they drank the milk, letting the bowls pass from man to man.

The warriors began to dance, singing Ingomo’a , the Zulu war song, and the Boers withdrew towards the centre of the field to make more room for the warriors. At the same time I heard Dingane order a messenger to hurry to the white prayer-conjurer to tell him that he need not be afraid, and I wondered greatly what that could mean; why should the white prayer-conjurer now be afraid of a dance which he had seen before? Then Dingane rose and went, followed by all, through the crowd to Retief, saying farewell to him by the hand and wishing him a safe journey, hambla gachle . The Boers waved their hats, and the king went towards his own house, at the gate of which I saw the chief of the regiment standing as if awaiting some order.

Suddenly the king stopped and shouted in a resounding voice: “Bulalani abatakati!” (kill those witches) and went behind the enclosure, covering his face with the edge of his cloak.

We advisors stood there as if petrified, and before we could say or do anything, the regimental commander had echoed the cry to his warriors: “Bulalani abatakati!” There was a clatter of advancing feet, accompanied by a shuddering roar, and through the cloud of dust rising into the sky we saw the warriors rushing at the Amaboonai and heard the whir of sticks. The strangers snatched up their knives and defended themselves bravely, but the resistance was broken before they could count to twice a hundred, and most of them were dragged still alive outside the gate, to the Hill of Death, where they were all brutally executed. How? Ah, I won’t tell you that—they were all murdered in one heap, and that was the end of their story. Only one of the group was saved, a young man named Macumazana, or Supervisor, the interpreter, whom only Dingaan spared and later completely freed, I believe, because the young man was English.

I and the other councilors went in silence to the king’s house. He stood before his door, and raising our hands we saluted him without uttering a word. He laughed nervously, like a person with a bad conscience, and said, looking at us insolently:

“When the vultures this morning plucked their feathers and screamed for food, they had no idea that such a feast was coming as I, my good advisor, had prepared for them. Nor do you, my good advisor, seem to have known what a great king Heaven has made you to rule, or how deep the intentions of that king who watches over the welfare of his people really are. Now my country is free from those white witches, about whose steps the great Elephant-dead man chattered at his death-bed, or at least it will be soon, for this is only the beginning. You messengers!” he shouted to the few men standing behind him, “hurry to carry the king’s word to the regiment on the other side of the ridge. The king orders the army to attack Natal at once and kill all the Boers there, women and children too. Go!”

The men saluted the king with a bayéte cry and hurried away as quickly as spears shot from the hand of a thrower, disappearing from our sight. But we, the advisors, the members of the amapakati , stood still, silent.

“Are you satisfied now, Mopo Makedama’s son?” continued Dingaan, turning to me. “I have always been telling you about these white people and the things they will do, and behold, I blew on them and they disappeared. Tell me, Mopo, are all those Amaboonanoids dead? If any are still alive, I want to talk to them.”

I looked Dingaan in the eye and said:

“They are all dead, and you are dead too, O king.”

“It is better for you, you dog,” said Dingaan, “to speak your thoughts more clearly.”

“May the king forgive me,” I replied, “but I meant what I said. You cannot kill these white men to extinction, for they are many races and not just one, and the sea is their home; they emerge from the lap of black waters. Destroy those who are already here, and you will see that others will be avenged more and more. You have struck now, but next time they will strike. They have now humbled themselves to the point of blood before you, but the day dawns when you will have your turn to bleed in your blood before them. You must have lost your mind, O king, to do this, for this will be your death. I, the king’s servant, have spoken. May the king’s will be done.”

I expected the death blow at once, for in the fury of my heart over the heinous crime I had committed I did not spare my words. Dingaan looked at me three times, and his face was a terrible one, with features distorted by rage, rage mingled with fear, and I waited calmly to see which would prevail, rage or fear. When at last he was able to speak, he uttered at last one word, “Go!” and not two, “Kill him!” And we departed at once, leaving the king alone.

My heart was very heavy, my father, for of all the evil designs I had seen, this treacherous murder of the Amaboonai, with their wives and children, seemed to me the most heinous. Yes, in the country called Weenen, or the Tanner of the Weeping, about six hundred Boers were murdered at that time—wives and children too.

Tell me, my father, how can Umkulunkulu, who lives in the heavens above, allow such things to happen on earth below? I have heard white men pray to their God. They say they know him in every way—that he is called Power, Grace, and Love. Why then does he allow such things to happen—why are such persons as Chaka and Dingaan allowed to torment and torture mankind and to atone for the death of many thousands of people by the death of only one? Because of the wickedness of men, you say, but that cannot be, for should not the innocent suffer with the guilty—should not innocent children die by the hundreds? Perhaps there is another answer, but what am I, my father, to try to penetrate to the depths of those great things hidden from men. Wow! I, who am only an uncivilized brute, do not understand it, nor have I met with deeper knowledge and wisdom in the hearts of you white men. You know many things, it is true, but you do not know this; you cannot tell us where we were before we were born and where we go after we die, or why we live and why we die. You only hope and believe—and that is all; perhaps in a few days I shall be wiser than you all. I am very old, and the flame of my life grows weaker every day—it flickers only in my brain, where it is still bright and luminous, but soon it will go out there too, and then perhaps I shall understand everything.

IV.

WAR AGAINST THE HALAKAZES.

Now I want to tell you, my father, how the war of Umslopogaas and Susi-Galaz against the Halakaz was successful. After we set out on our journey home, Umslopogaas had immediately called together all the leaders of the tribe and explained to them that it was his most fervent hope that the axe people would not always have to be just a small and insignificant tribe; that they would grow into a mighty nation, with livestock numbering in the tens of thousands.

He was asked how this could be done—whether he intended to make war on Dingaan himself? Umslopogaas replied that it was not his intention, on the contrary, he had decided to try to gain the king’s favor. He told the men about the Halakazi tribe of Swaziland and the Lily girl, and explained that his intention was to go on a military expedition against that tribe. Some agreed at once, but others resisted, and the heated discussion that arose over the question lasted late into the evening. At last Umslopogaas’ patience ran out and he rose, saying that he was the chief of the axe people by right of the owner of the sword and no one else, and that since he had decided to make war, everyone had to be content with that and that was good enough. If anyone still wanted to oppose him, let him come forward to fight him, and then let the winner decide the matter. No one answered, for there was no one among those present who would have wanted to stand in the way of the Weeper. So it came to pass that it was decided to wage war against the Halakaz, and Umslopogaas sent messengers to summon all the men fit for battle.

But when Zinita, his wife, heard of it, she was in a rage, and scolded Umslopogaas angrily, and cursed me, Mopo, the mouth of Dingaan, because I had, as she rightly said, put those ravings on the head of the Slayer. “Why can’t you live here in peace and plenty, you strange man, but you want to go to war against people who have done you no harm, on which journey you yourself oppress, or at least cause suffering to others? You say you want to take the girl to Dingaan in order to gain this favor. Hasn’t Dingaan got more girls than he can count? Is it not just that you are tired of our present wives and want to have the girl for yourself? To gain favor! By remaining quiet you will gain favor the best of all, Bulalio. If the king sends his warriors against you, then fight, you weak-minded rascal!”

Zinita spoke so insultingly—in her anger she blamed everything she had in her heart, and Umslopogaas could not challenge her to a fight. Umslopogaas was allowed to listen as patiently as he could, for it often happens, my father, that even the greatest men are often insignificant under their own roof. He knew, moreover, that Zinita spoke so bitterly only out of love for him.

On the third day all the men fit for battle were assembled, and there were about two thousand of them, all brave and capable warriors. Umslopogaas came out of his hut with Wolf-Galazi and made a stirring speech to his regiment, explaining at the same time the purpose of the expedition. The warriors listened in silence, and it was quite clear that one was of one mind and another of another, as had been the case with the leaders in the consultation. Then Galazi stepped forward and said that he knew the caves and secret paths of the Halakaz and the number of their cattle, but the men still seemed to hesitate, whereupon Umslopogaas added the following words:

“Tomorrow at dawn I, Bulalio, the wielder of the sword and the leader of the axe people, will set out against the Halakaz, accompanied by my brother Susi-Galazi. If even ten men go with us, then we will go. Now choose, warriors! Let those who want to come, the rest stay home with the akkos and children!”

A thunderous shout echoed from the ranks:

“We will come with you, Bulalio, to victory or death!”

In the morning the troops left, accompanied by the mournful lamentations of the women of the axe people. Zinita alone did not shed tears, but grumbled angrily and predicted that everything would end unhappily. She did not even say goodbye to her husband, but nevertheless burst into tears when he left.

Umslopogaas and his army rushed forward rapidly, starving and thirsty, until they finally reached the Umswazi country, and after some time through a narrow and high mountain pass into the territory of the Halakaz. Wolf-Galazi had feared that the pass was occupied, for he knew that messengers had hurried in droves to warn the Halakaz, although they had not disturbed anyone along the way; they had also taken only as much cattle as was needed for the warriors’ provisions. But there was no one in the pass, and when they had passed through, they rested, for the evening was already late. At daybreak Umslopogaas looked at the open plain spreading out before him, and Galazi showed him a long, low hill, which was about a couple of hours’ journey away.

“There, my brother,” said he, “is the city of Halakazi, where I was born, and on that hill is that great cave.”

The journey continued, and before the sun had even risen high, they reached a village on the hill, from the other side of which they could hear the sound of horns. The whole army of the Halakaz—a very large army —was charging across the plain towards them!

“They must have gathered their men,” said Galazi. “There are at least three of them for every one of us!”

The warriors had also noticed the enemy, and the courage of many began to fail. Then Umslopogaas shouted:

“The Halakazi dogs are there, my child, they are many and we are few, but can anyone tell that we, the sons of the brave Zulu, have fled from the Halakazi dogs? Will we allow our wives and children to sing that song in our ears, O you valiant warriors?”

Some shouted: “No way!” but others remained silent, which is why

Umslopogaas continued:

“Turn back, all you who will; there is still time, but those who are men will follow me. Or go all of you, if you wish, and leave the decision of this matter to the Weeper and the Wading Warden.”

Now a mighty cry rang out:

“We will die together as we have lived!”

“Do you swear?” shouted Umslopogaas, lifting the Weeper high.

“We swear it by the brave man,” replied the warriors.

Then they prepared for battle. The younger ones were placed on a slope, which was very rocky, for it was best to sacrifice them first, and Wolf-Galazi was appointed their leader, but Umslopogaas remained with the older and more experienced warriors on the summit of the mountain.

The Halakazi were already near, and there were four full regiments of them; the whole plain was black with warriors, the air trembled with their roar, and their spears flashed like darting lightning. They stopped at the foot of the slope and sent a herald to ask what the axe-people wanted. Bulalio replied that he wanted these three things: the head of the chief; from then on Galazi would be their chief, the girl named Lilja, and a thousand cattle. If the demands were granted, he would spare the Halakazi; if not, he would destroy them completely.

The herald returned to his people and announced the answer he had received in a resounding voice. Unbridled laughter echoed from the ranks of the Halakaz, making the tanter tremble. A flame of anger burned on Umslopogaas’ forehead, and he shook the Weeper towards the enemy.

“You will sing another song before the sun goes down!” he shouted, and went from row to row, addressing the men by name and encouraging them with brave words.

The Halakazi answered with a furious shout and charged towards the youths led by Galaz, but the soft ground at the foot of the village made it difficult to pass, so that Galazi and his men attacked them with full force, killing a large number of the enemy. But the enemy was so superior that his resistance was soon broken, and before long the battle raged on all sides. However, Galazi carried out his task so skillfully and his young warriors fought with such fury that before they fell or were forced to retreat, the entire enemy army was in battle with them alone. Twice Galazi rallied his men to the attack, causing such confusion among the enemy that all the companies and regiments were finally in complete confusion. However, he was finally forced to retreat, as more than half of the men had fallen and the rest were pushed back in furious fighting up the slope.

Umslopogaas and his men watched the battle from the top of the hill and exclaimed when they saw the enemy’s confusion: “That commander of the Halakazi dogs is quite a ram’s head! There are no men in reserve, and Galazi has already broken his battle formation and mixed the regiments together like milk and cream in a bowl. They are no longer a flock of sheep , but a flock of sheep.”

The warriors lifted their feet, leaned on their spears, and exchanged a word with each other from time to time. “Well struck, Galazi! Wow! There’s another man swinging! Brave boy! What a fine weapon that club of yours is!” The battle began to rage and the warriors’ faces grew grim. Their fingers curled ever tighter around the spear shaft.

One of the chiefs finally shouted to Umslopogaas:

“Say, Bulalio, isn’t it time for us to get to work too? Our legs are getting stiff from standing naked.”

“Wait a little longer,” I replied to Umslopogaas. “Let those dogs tire themselves out first. Let them run wild until they’re exhausted, I say.”

While he was still speaking, the Halakazi formed for an attack and forced Galaz to retreat. So, he was finally forced to retreat with the remnants of his troops, and the Halakazi rushed up the slope after them, their leader in the forefront, surrounded by their bravest.

Umslopogaas leaped up, roaring like a bull. “Now, wolves!” he roared.

The ranks surged forward like a great wave and began to roll down the slope with irresistible force. The Slayer rushed ahead, on the Weeper’s rise, and his stride was swift—so swift that he left his warriors a long way behind. Galazi felt the ground shake, heard the thud of feet, and turned to look, and at the same moment Bulalio sprang past him like a deer. Galazi wheeled after him, and the Wolf-men rushed down the slope, about four spear-lengths apart.

The Halakaz tried to organize themselves to repel the attack, and their chief, surrounded by spears and lances, happened to be in the path of the rushing Umslopogaas. He pressed straight ahead, and twenty spears turned to meet him, and twenty shields rose into the air—a fence through which no one could penetrate alive. But Bulalio was a hero who could handle even that—and all by himself! See how his step stiffens, he stoops, and now he leaps—high into the air; his feet brush the heads of the warriors and bounce on the raised shields. The warriors strike upward with their spears, but he has flown over them like a striking eagle—there are now two chiefs in the fence of spears and shields. But not for long — The Weeper is lifted up, it falls, and neither shield nor scepter can ward off its blow, both are shattered and the Halakazi are without a leader.

The shields are now turning towards the center. You fools! Galazi is upon you! What was that? Turn and see, warriors, how many bones are intact in him, whom the Guardian hits with full force. What! Now another one has fallen! Press closer together, shieldmen—closer! Ah, you are fleeing!

The wave has rolled on the shore. Hear its roar—hear the clang of the shields! Stand firm, Halakaz—stand firm! There are only a handful of them. Look! What! Through Chaka’s head! You will retreat, you will be pushed back—the wave of death spreads with a roar over the sand—the enemy sways hither and thither like a weed uprooted, and the roar heard on every side begins to die down to a low murmur. ” S’gee !” whispers the murmur. ” S’gee! S’gee !”

Forgive me, my father. What have I, an old man, to do with the charm of war and the din of battle? But to die in such a battle is still more wonderful than life. I have seen such battles—I have seen many of them, my father. Yes, they knew how to fight in those days, they really did, but no one was a match for Umslopogaas, Chaka’s son, and his blood brother Wolf-Galaz! Well, they swept the halakazi out of their way as easily as a girl sweeps dust from your hut, as the wind blows away withered leaves. The battle was decided before it had even had time to properly begin, for the enemy turned to flee.

The victory, however, was not yet achieved. The Halakazi had been defeated in the open field, but there were still enough of them alive to defend the great cave, where the final decision had to take place. Thither Bulalio hurried with his remaining men. Unfortunately, many had fallen; but could the death of a warrior be more glorious? And those who remained were truly elite, for now they knew that they could not be easily defeated as long as the scythe and the club led them.

They stood now looking at a rising hill before them, about three thousand paces in circumference. The hill was not high, but inaccessible, with its steep sides only that of rock rabbits and lizards could climb. No one was to be seen. The town near by was also quite deserted, and yet the ground was full of the footprints of animals and men, and from within the mountain came the sound of cattle bleating.

“This is the nest of the Halakazi now,” said Wolf-Galazi.

“A nest indeed,” said Umslopogaas; “but how shall we get at the eggs? The tree is without branches.”

“But there’s a hole in the frame,” Galazi replied.

He went ahead and soon they came to a place where the ground was trampled into mud, like the gate of a cattle pen. There was a shallow cave-like opening in the mountain wall, like the vaults your white men built. But now the opening was filled up to the ceiling with large boulders, so that it was unthinkable to try to get in through it. The passage had been filled in after the cattle had been driven in.

“We can’t get out of here,” said Galazi. “Follow me.”

We went around to the north side of the mountain and there, a couple of spear throws away, stood guard, a warrior who disappeared as soon as he noticed the arrivals.

“There’s a hole where the fox has slipped into his den,” said Galazi.

They hurried to the spot and found a hole in the rock, barely bigger than an anteater’s burrow. Light was shining from the hole and sounds were heard.

“Where is the hyena now, looking for a new den?” cried

Umslopogaas. “A hundred cattle to him who crawls through and opens the way!”

Two young men, enchanted by victory and desiring nothing but fame and booty, leaped forward, exclaiming:

“Here are the hyenas, Bulalio.”

“Then I will go through the hole!” said Umslopogaas, “and let him who gets through hold his own long enough for the others to come to his aid.”

Both charged the hole, and the one who had arrived first threw himself on his knees and crawled in, leaning on his shield and his spear extended forward. The hole went dark for a moment and the man’s movements could be clearly heard. Then there were a couple of loud blows, and the light appeared again. The man was dead.

“He had a bad guardian spirit,” said another; “let’s see if mine is better.”

He dropped to his knees and crawled in like the other, but with the difference that he held the shield over his head. After a moment the blows were heard to fall, crashing against the bull’s-skin shield, and then a muffled groan. He too had been killed, but it seemed that his body had been left in the hole, for no light was visible. And so it had been. After receiving the blow, the man had retreated back into the hole, dying there, and no one came from the other side to pull him out.

The warriors stared into the hole, helpless and bewildered, for it was a sad thing to die like that. Umslopogaas and Galazik also looked at the hole with gloomy looks.

“Wolf is my name,” said Galazi, “and a wolf must not be afraid of the dark; besides, those within are my people, so it is my duty to be the first to greet them,” and he threw himself on his knees without further ado. But Umslopogaas, who had peered into the opening once more, cried out: “Wait, Galazi! I have found a way, and I will go before you. Follow me. And you, my children, shout loudly so that no one can hear us move, and if we get through, you will follow quickly after us, for we cannot hold the mouth of the opening long. If I die, choose for yourselves another leader—Wolf-Galazi, if he is still alive then.”

“Speak not of me, Bulalio,” said Galazi, “for we shall die together as we have lived.”

“So be it, Galazi. Then choose someone else and do not try to enter this way again, for if we are unlucky, the others will not be able to get in either. Get yourselves something to eat and wait until those jackals are in pain—then be on your guard. Farewell, my child!”

“Goodbye, father! Be careful that we don’t have to be left here wandering abandoned like sheep without a shepherd.”

Umslopogaas took off his shield and crawled into the hole, holding the spear in front of him, and Galazi followed at his heels. When he had gone about six spear lengths, Umslopogaas stretched out his hand and, as he had guessed, touched the leg of the man he had just killed. The ever-wise Umslopogaas now did this: he thrust his head under the man’s thighs and gradually slid forward, so that at last the man’s body was completely on his back, and to prevent it from falling he held it by the ankles with the other hand. Then he crawled forward again and found himself approaching the mouth of the hole, which was shaded by immense boulders, so that the place was almost dark. “This is very convenient,” thought Umslopogaas, “for here one cannot distinguish the dead from the living. Perhaps I shall even see the sun again.” At the same time he heard the Halakazi warriors talking at the mouth of the hole.

“I don’t think those Zulu rats will like this,” someone said, “they’re afraid of the rat-catcher’s stick. It’s great sport,” and someone laughed.

Umslopogaas pushed forward as quickly as possible, holding the dead body on his back, and suddenly came to an open space at the mouth of the hole, in the gloomy shadow of a large boulder.

“By our lovely Lily!” cried one warrior, “there is a third! Here is for you, you Zulu rat!” And he struck the dead man hard with his club. “And here!” cried another, driving his spear through the dead man with such force that the point wounded Umslopogaasi too. “And here! And here! And here!” repeated the others, as they struck and stabbed.

Umslopogaas now made a moaning sound and then lay still. “That’s enough,” said the warrior who had struck first. “That one will never return to Zululand again, and I think few will want to come and see what he has become. Let’s stop this game already. Hurry and get the stones with which we stopped up the hole.”

He turned away like the others, and that was exactly what Umslopogaas had expected. He dropped the body from his back and sprang to his feet. The men heard something and turned, but at the same moment the Weeper flashed, and the man who had sworn by Lily fell to the ground. And before the others had time to think, Umslopogaas was standing on a large boulder like a deer against the sky.

“A Zulu rat is not so easily killed, you flies!” he shouted, as warriors began to swarm towards him from all sides. He struck right and left, and so quickly that he could hardly distinguish the blows, for he only pecked again with the spike of his spear. And though the assailant could hardly see, men fell on every side, my father. Now the enemies had him completely surrounded, trying to roll up the boulders like a torrent rushing against a rock. Blows were aimed at him from all sides, but the Weeper could easily ward off those from the front and sides. The greatest danger threatened from behind. Umslopogaas had already received a wound in his neck, and the spear was already rising to pierce his back, when at the same time the hand that held it went limp forever.

Galazi had rushed to the rescue and was in time. The guard swung wildly and the blows rained down so frequently that Umslopogaas’ back was soon free. The veiks were flailing and raging like evil spirits, and in a moment tufts of axe-folk warriors began to appear from the opening, one after another, and rested arms were mixed with the din of battle. The men appeared quickly like ghosts, plunging into the fight as others plunge into water—now there were ten of them, now twenty—and the Halakaz turned to flee, for resistance was of no avail. The rest of the warriors of the valiant man crawled in peace, and the evening was already beginning to fall before all were inside.

V.

NADA.

Umslopogaas inspected his men, and then said:

“It’s already very dark, but we must drive those rabbits out of their hiding places. You know their holes and you know the roads, Galazi, you take my place and lead us.”

Galazi obeyed the command and turned left, and came to a wide clearing with a well in the middle, full of cattle. After a while he turned left again, and now came to the mouth of a large cave, which was quite dark, but nearby was a large pile of dry sticks from which torches could be made.

“There is light for us there,” said Galazi, pointing to the pile, and every other man snatched a torch into his hand, which they lit from a nearby blazing fire. Then they charged in, torches brandished and spears raised. The Halakaz struck back for the last time, and soon a fierce battle raged in the cave, which did not last long, however, for the enemy’s courage had gone. Wow! I do not know how many of the enemy were killed in that battle, but there were many. After the Umslopogaas campaign, only the name of the Halakaz tribe remained—so utterly were they defeated. The warriors of the Axe People drove the enemy from the cave to the open place where the cattle had been driven, and there, among the animals, the battle finally stopped.

Umslopogaas saw a group of men huddled together in a corner of the cave as if to protect something. He charged forward, Galaz and the others following, and as the group dispersed, he saw a tall, slender man leaning against the rock wall, holding a shield before his face.

“Poor coward!” he roared and struck. The spear pierced the shield, but did not hit the head behind it, but struck the rock with a flash, so that sparks flew. At the same time a sweet voice said:

“Ah, don’t kill me, warrior! Why are you angry with me?”

The shield had caught the blade of the scythe and slipped from the keeper’s hand, but there was something in the tone of the voice that seemed to prevent Umslopogaas from striking again; it was as if the tone of that voice had awakened some childhood memory in his heart. The torch burned dimly, but he held it forward in order to examine more closely the man who was pressed against that wall. The suit was that of a man, but that body was not that of a man, but rather that of a young, beautiful woman, almost white in color. The hands that covered her face slowly fell away, and now Umslopogaas could see her clearly. The eyes were bright as stars, the curly hair waved down to her shoulders, and the girl’s whole being was so beautiful and charming that no other had ever been seen among our people. And just as that chord of voice had brought back to Umslopogaas a memory of something he had long since lost, so those radiant eyes seemed to look at him through the darkness of years, and that beauty brought back to him, he himself did not quite know what.

He looked at the girl standing there in all her beauty, and she stared at the strong, blood-red, terrible-looking warrior. They looked at each other for a long time, the flickering flame of the torch illuminating them, the cave wall, and the Weeper’s broad blade as the battle raged around them.

“What is your name, you who are so beautiful to look at?” asked Umslopogaas at last.

“Lilyflower is my name now, but I used to have another name. I was once Nada, daughter of Mopo, but both the name and all I loved are dead, and I will go to them. Kill me and end my pain. I close my eyes so I won’t see the flash of your great killer.”

Umslopogaas looked at him again and the Weeping Man let go of his hand.

“Look at me, daughter of Nada Mopo,” he said in a low voice, “and tell me who I am.”

The girl looked and bent forward eagerly and looked again. The features of her face stiffened, and there was an indescribable astonishment on them. “Through my heart,” she cried, “you are Umslopogaas, my brother who is dead and whom I have only loved in death and in life.”

Umslopogaas pressed her to his chest and kissed her, the sister he had found again after many years, and Nada kissed him.