The childhood and adolescence of Allan’s friend Umslopogaas

The story of the Zulu caravans

Letter

H. RIDER HAGGARD

Translated from English into Finnish

OEN [OE Nyman]

Helsinki, Publishing Company Book, 1922.

CONTENT:

To the reader.

I. Chaka’s prophecy.

II. Mopo in trouble.

III. Mopo’s daring return.

IV. Mopo and Balkan’s escape.

V. Mopo becomes the king’s physician.

VI. The birth of Umslopogaas.

VII. Umslopogaas before the king.

VIII. The defeat of the magicians.

IX. Umslopogaas’ disappearance.

X. Mopo’s trial.

XI. Baleka’s advice.

XII. The story of Wolf-Galazi.

XIII. Galazi becomes the king of wolves.

XIV. Wolf-scoundrels.

XV. The death of the king’s men.

XVI. Umslopogaas goes to fight Tappara.

XVII. Umslopogaas becomes the chief of the axe people.

XVIII. Baleka’s curse.

XIX. Masilo moves to Duguza.

XX. Mopo negotiates with the prince.

XXI. Chaka’s death.

TO THE READER.

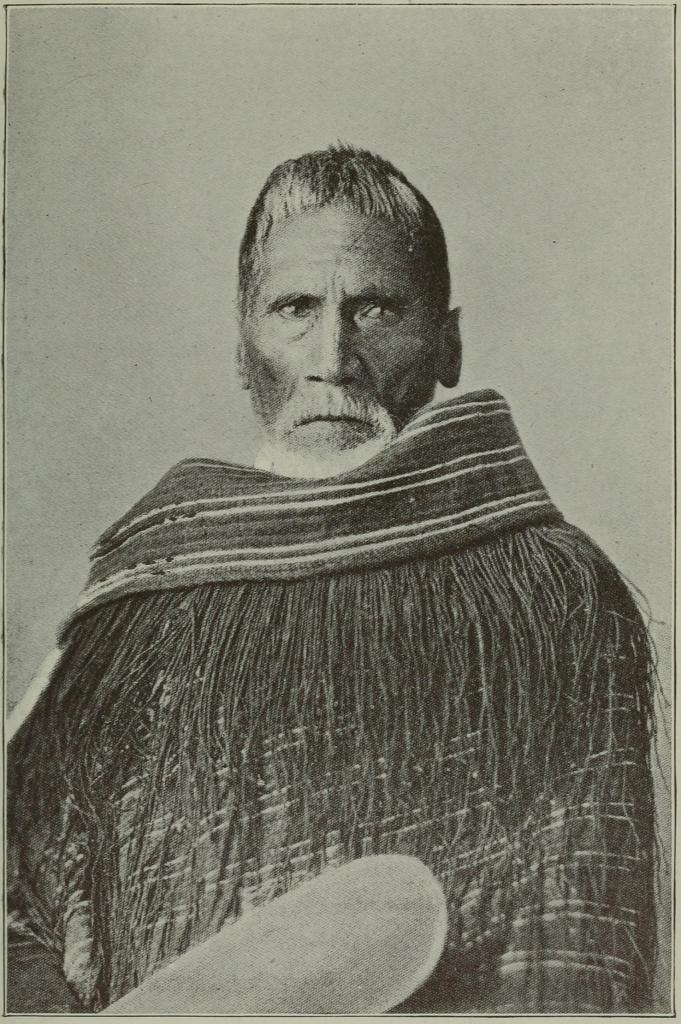

In writing this book the author had another purpose than simply to create a cruel account of the life of a savage people. While still a young man he was fortunate enough to reach South Africa. There he came into contact with persons who had lived for forty years among the Zulu people, whose history, heroes and customs they knew very well. From them he heard many legends and stories, which are now rarely spoken of and which will soon be forgotten altogether. At that time the Zulu were still a united people, but now they have been destroyed and the intention of the white rulers is to completely extinguish the warlike spirit for which that people was known, and to develop in its place a hobby of peacemaking. The Zulu military institution, probably the only one of its kind in the whole world, is already a thing of the past; it and its supporters have gone into eternal silence, at Ulundi. Chaka created it, starting from a small group. When he appeared in the early nineteenth century, he was only the chief of a small tribe, and when he died in 1828, pierced by the spears of his brothers Umhlangana and Dingane and his servant Mopo, or Umbopo, as he was also called, he was the ruler of all South Africa, and it is said that he killed another million people in his quest for power. In the early nineteenth century, South Africa was relatively densely populated. During Chaka’s reign, the population decreased considerably. This book has attempted to portray the true character of that great genius and at the same time a most cruel man, and also to present a true picture of his brother and successor Dingane. The author’s purpose has also been to present in narrative form the reasons, ideas, and purposes which inspired these kings and their supporters, and to bring to light events in African history which are now mentioned only in a few accounts.

It is clear that such a task has been difficult, because the author must have for a time forgotten his level of education entirely and thought and spoke like an ancient Zulu. Because of our sophisticated age, not all the atrocities committed by the Zulu tyrants can be described, and their details have therefore been greatly reduced. Most of the events narrated are basically true. By “black hero” here is by no means Chaka, but Umslopogaasi, who may be said to represent the Zulu race in its most manly and noblest form. We hope that young readers will be fond of following his fate.

I.

THE PROPHECY OF THE CHAKA BOY.

You ask me, my father, to tell you the story of young Umslopogaas, the owner of the Iron Queen or Weeper, who was called Bulalio the Slayer, and of his love for Nada, the most beautiful of the Zulus. The story is long, but you will stay here for many more evenings, and if I live long enough to tell it, I will tell it in full. So harden your heart, my father, for my story is very sad; even now, when I think of Nada, tears creep through the ice that darkens my old eyes.

Do you know, father, who I am? How could you know? Think that I am an old, old magician named Zweete. Others have thought so for years, but Zweete is not my real name. Few have known it, for I have hidden it in the depths of my heart, and though I live now under the white man’s law, and the great queen is my ruler, the assegai can find its way into my chest. Therefore no one knows my real name any more.

Look at this hand, my father—no, not this, whose fire has dried up; look at my right hand. You see it, but not I, who am blind. Yet I still see it in my spirit as it once was. Yes! I see it strong and red—red with the blood of two kings. Hear, my father; bend nearer and hear. I am Mopo—ah! I felt you start; you started like a regiment of bees as Mopo passed its ranks, examining it with the assegai in his hand, from the blade of which Chaka’s heart-blood was slowly dripping to the ground. I am Mopo, he who killed King Chaka. I killed him with Princes Dingaan and Umhlangana, but I struck the mortal wound, and without me he would never have been slain. Him I killed with the princes, but Dingaan I and another killed alone.

What did you say? “Dingaan died at Tongola’s.”

That’s right, he died, but not there; he died on the haunted mountain; he rested in the bosom of that old petrified witch who sits up there waiting for the end of the world. But I was on the haunted mountain too. My feet were still swift then, and my revenge gave me no rest at night. I walked all day, and in the evening I found him, I and another, and we killed him—ah! ah!

Why am I telling you this? What has this to do with the love of Umslopogaas and Nada? I will tell you. I killed Chaka for my sister Baleka, who was Umslopogaas’ mother, and because Chaka had murdered my wife and children. I and Umslopogaas killed Dingaan for Nada, who was my daughter. Great names are mentioned in my story, my father. Yes, many have heard those names. When warriors roared them in the heat of battle, I have felt the mountains tremble and seen the sheet of water vibrate with the power of the sound. But where have they gone now? Silence has swallowed them up and they are spoken of only in the books of white men. I opened the gates to the owners of those names, and they entered the kingdom of shadows. I broke the bonds that bound them to this world. They disappeared. Ha! Ha! They disappeared! Perhaps their journey is not yet over, perhaps they creep around their deserted huts in the form of snakes. I would like to know those snakes so that I could crush their heads with my heel.

Down there in the royal cemetery there is a chasm. And at the bottom of the chasm are the bones of Chaka, the king who died for Baleka. Far away in Zululand there is a deep chasm in the ghost mountain. At the bottom of that chasm are the bones of Dingaan, the king who died for Nada. The fall was dizzying and he was heavy; his bones were crushed to crumbs. I went to see them when the jackals and vultures had done their work. I laughed three times then and came here to die.

It has been a long time, and I am still alive, though I wish nothing more than to die and walk the path that Nada has walked. Perhaps I have lived only to tell you this story, my white father, so that you may tell it in turn to other white men, if you wish. How old am I? I do not know. Very, very old. If Chaka were alive, he would be my age now. There is no one alive that I knew when I was a boy. I am so old that I must hurry. The grass is withering and winter is coming. Yes, even now as I speak I feel winter cramping my heart. I can sleep in the cold, perhaps then I will wake up to the beauty of spring.

* * * * *

Before the Zulus were united into one nation—I will begin at the very beginning—I belonged to the Langen tribe. Our tribe was not large; later the fighting men formed a full regiment in Chaka’s army; there were perhaps only two or three thousand of them, but they were brave. Now they are all dead, their wives and children with them—that tribe no longer exists at all. It has disappeared from the face of the earth, and I will tell you little by little how it happened.

Our tribe lived in a beautiful plain; the Boers, whom we call the Amaboon, live there now, I am told. My father, Makedama, was the chief of the tribe, and his huts were on the top of a hill, but I was not the child of his first wife. One evening, when I was still so small that I could hardly reach a man at the elbow, I went with my mother to watch the cattle being driven to the pasture. My mother was very fond of cows, and especially of one with a white head, which followed her everywhere. My sister Baleka, then only a little child, was in my mother’s arms. We walked on until we met some boys who were driving the cows. Mother lured her white-headed pet to her and fed it with succulent leaves which she had brought with her. The boys continued to drive the cattle, but the white-headed cow remained with mother. She said she would bring it with us when we returned home. Then the mother sat on the grass to suckle her little child, and I played around her while the cow was ruminating nearby. After a while we saw a woman coming towards us across the plain, and her gait showed that she was very tired. She had a pack on her back and was leading a boy by the hand, who was about my age, but taller and more stocky than I. We waited a long time until the woman reached us, when she fell to the ground, for she was very exhausted. As we passed by, we saw by her hair that she was not of our tribe.

“Hello to you!” he said.

“The same to you!” replied my mother. “What are you looking for?”

“Food and a place to sleep,” said the woman. “I have come a long way.”

“What is your name—and your tribe?” asked my mother.

“Unandi is my name; I am the wife of Senzangacona, the chief of the Zulu tribe,” replied the stranger.

Our tribe and the Zulus had recently been at war with each other, Senzangacona had killed some of our warriors and robbed a lot of cattle, so that when my mother heard Unandi’s words, she jumped up in a rage.

“And you dare come here to ask me for food and shelter, you wife of a wretched Zulu dog!” he shouted. “Go away, or I will have my girl drive you out of our territory with the whip!”

The woman, who was very beautiful, waited until my mother had ceased speaking those angry words; then she looked up and said, with a delay:

“There is a cow with udders full of milk at your disposal; will you not give me and my son a little?” And he took a cup from his mouth, which he held out towards us.

“No,” said my mother.

“We are thirsty after our long journey; give us a cup of water.

We have not found water for many hours.”

“No, you dog’s companion; go find yourself some water.”

The woman’s eyes filled with tears, but the boy folded his arms across his chest and frowned. He was a very handsome boy, but as he frowned his bright, black eyes darkened like the sky before a thunderstorm.

“Mother,” said he, “we are no more tolerated here than there,” and he nodded towards the Zulus. “Let us go to Dingiswayo; the Umtetwa tribe will take us in.”

“Yes, let us go, my son,” replied Unandi, “but the journey is long, and we are tired; we are getting tired on the road.”

I heard everything and my heart was pounding; I felt sorry for the woman and the boy, for they looked so tired. Without saying a word to my mother, I snatched up the cup and hurried to a nearby ravine where there was a spring. I filled the cup and ran back at once. My mother intended to prevent me from fulfilling my intention, for she was very angry, but I rushed past her and handed the cup to the boy. My mother let the boy drink in peace, but all the while scolded the woman in the most bitter words, saying that this man would bring us only harm, and that her guardian spirit said that the boy would only add to the burden of suffering. Ah, my father, her guardian spirit spoke the truth. If that Unandi had then perished in the desert with her children, the bones of my tribe would not now lie in the ravine near the village of Cetywayo, nor would our flourishing region be a desolate wilderness.

While my mother spoke, I stood silently by the white-headed cow, and little Baleka wept. Having taken the cup, Unand’s son did not offer water to his mother, but drank two-thirds himself, and I think he would have drunk it all if his thirst had not been quenched. Having drunk, he handed the cup to his mother, who drank what was left. Then he took the cup again and came to us, cup in one hand and a short stick in the other.

“What is your name, son?” he said to me, as a rich and powerful man speaks to a poor and insignificant one.

“Moped is my name,” I replied.

“And what is your tribe?”

“The Langen tribe.”

“Very well, Mopo; let me tell you my name now. I am Chaka, son of Senzangacona, and my tribe is called the Amazulu tribe. Let me tell you more. Now I am small and my tribe is only a small tribe, but I will grow big, so big that my head will disappear into the clouds; you will look up and not be able to see it. My face will blind your eyes; they are bright as the sun and my tribe will swell with me and fill the whole world. And when I am big and my tribe is great and when we have trodden the earth smooth as wide as a man can ever walk, then I will remember your tribe—the tribe of the Langen, who did not give me and my mother a cup of milk when we were tired. You see this cup; then the blood of as many men will flow as this cup can hold drops when it is full of blood—the blood of the men of your tribe. But because you gave me water, I will spare you, Mopo, only you, and I will make you a great man. You will be profitable and fattening in my shadow. I will never do you any harm, no, not even if you offend me, I swear it. But that woman,” and he pointed to my mother, “let her hasten to her death, so that I need not show her how long the death struggle can last. I have spoken.” And he gritted his teeth and shook his stick at us.

My mother was silent for a moment. Then she burst out:

“That little liar! He talks as if he were a man of his time, doesn’t he? The calf shoots like a big bull. I’ll teach him another note—for such a childish rascal, a bird of evil spirits!” And setting Baleka down, he nodded towards the boy.

Chaka stood there motionless until my mother was very close, when he raised his stick and hit my mother on the head so hard that she fell to the ground. The boy burst out laughing, turned and went on his way with his mother, Unandi.

These words, my father, were the first I heard Chaka utter, and they contained a prophecy that came true. His last words that I heard contained a prophecy too, and I am sure that this too will come true, and has already been partially fulfilled. In his first prophecy he said that the Zulus would unite into a mighty nation. And tell me, has it not happened? In the second he described their downfall, and they did. Are not the white men now preparing to attack Cetywayo as vultures gather around a dying bull? The Zulus are no longer what they were, and have no strength to repel them. Yes, yes, his words will come true, and my words are the song of a people doomed.

But I’ll talk about those other words in due time.

I went to my mother. After a while she sat up with her hands on her face. Blood flowed from the wound where the stick had struck her, down her arms and onto her chest, and I wiped it away with the grass. She sat like that for a long time. I wiped away the blood with the grass I had torn, the child cried and the cow mooed to be milked. Finally she let her hands drop and said to me:

“Mopo, my son, I have dreamed a dream. I dreamed that I saw that Chaka cub who struck me; he had grown to the size of a giant. He crept across mountains and deserts, his eyes blazing like lightning, and in his hand he brandished a small spear that was red with blood. He seized tribe after tribe, crushing them to pieces, and trampled their villages to the ground. Before him was the most beautiful summer, behind him the earth was black as after a terrible fire. I saw our tribe, Mopo; it was numerous and rich, everyone was happy, the men were brave and the girls were beautiful; I counted the children by the hundreds. I saw them again, Mopo. They were just bones, white bones, thrown by the thousands into a mountain chasm, and he, Chaka, stood on the edge of the chasm and laughed so that the earth trembled. Then I saw in my dream that you, Mopo, grew up “You were the only one left alive of our tribe. You crawled behind the Chaka giant, and with you were other men, big and royal in appearance. You struck him with a small spear, and he fell and became small again; he fell and cursed you. But you cried a name in his ear—the name of Baleka, your sister—and he died. Let us go home, Mopo, let us go home; it is getting dark.”

We got up and left, but I was completely silent, because I was scared, very scared.

II.

MOBILE IN TROUBLE.

I will tell you now how my mother obeyed the advice of the Chaka cub to die quickly. His stick had struck a wound on her forehead, which did not heal, but grew worse, and finally caused a bone abscess, which finally penetrated to the brain. Then my mother died, and I wept bitterly, for I loved her, and it was so terrible to me to see her cold and stiff, not uttering a word, no matter how hard I cried to her. Yes, then mother was buried and soon forgotten, and no one remembered her but me? – Baleka was still too small then – and my father took another young wife and was content. My life became very unhappy after that. My brothers did not love me, when I was much wiser and more ingenious than them. I beat them in using the assegai and in running, and they incited my father against me, so that he treated me badly. But Baleka and I loved each other, for we were both orphans, and he clung to me like a creeper to a lonely tree on the plain. Despite my youth, I understood perfectly that knowledge is power: although he who wields the assegai kills and destroys, he who leads the whole battle is greater and mightier than that killer.

I noticed that magicians and healers were feared everywhere. Everyone treated them with great respect, so that one medicine man, with only a club in his hand, put to flight ten warriors armed with spears. Therefore I decided to become a magician, for only they could slay their enemies by the power of their words. I began to delve into the profession of healers and study their knowledge. I sacrificed and fasted alone in the wilderness far away, performed all those tasks that you have heard of, and I learned much; in our witchcraft there is as much true wisdom as false deception – you know that, my father, for otherwise you would not have come to inquire about your lost oxen.

Thus the years passed, until I was twenty years old—that is, a full man. I had learned all that could be learned alone, so that I went to the chief magician of our tribe, whose name was Noma. The one-eyed old man was very cunning and wise, from whom I gained much knowledge and learned many clever tricks, but at last he began to envy me and prepared a trap for me to make me harmless. It so happened that one of the richest men of our neighboring tribe had lost some cattle and came bringing gifts to ask Noma to find out where the cows had gone. Noma tried his best, but could not find the animals; the eyes of his soul saw nothing. Then the strange chief became angry and demanded his gifts back, but Noma would not give up the goods he had already taken possession of, and heated words were exchanged. The chief swore to kill Noma; Noma threatened to bewitch the chief.

“Silence,” I said, fearing bloodshed. “Be still and let me see if my spirit will tell me where the animals are.”

“You are only a boy,” replied the chief. “Can such a boy know anything?”

“We’ll see very soon,” I said, taking the witch’s broom in my hand.

“Let the bones be!” Noma growled. “We will not ask for anything more from our lives for that son of a bitch.”

“He will take the bones,” answered the chief; “and if you try to stop him, I will make the sun shine through you with my assegai.” And he raised his spear.

I then hastened to begin and threw the dice. The chief sat before me and answered my questions. You know, my father, that magicians sometimes know where lost objects are, for our ears are long, and sometimes the guardian spirits tell them everything clearly, as I was told a couple of days ago where the oxen are. Well, my spirit awoke. I knew nothing before about the chief’s cattle, but my spirit told me everything, and I listed the animals to him one by one, every color, every age—in a word, everything. I also told him where they were, and how one had fallen into a stream and lay drowned on its back at the bottom, the other hind leg caught in a branch of a root. I told the chief exactly what my spirit told me.

He was now very pleased, and said that if I had seen rightly, and he found his animals, the gifts would be taken from Noma and given to me; and he asked the men who were sitting around us, and there was a large crowd, whether this was not justice and fairness. “That is so,” they all answered, and promised to see that it was done. But Noma was silent, and looked at me maliciously. He knew that I had spoken rightly and truly, and was therefore furious. The matter was not altogether a trifle: the lost herd was quite large, and if it were found in the place I had advised, I would be considered by everyone to be a more accomplished and greater magician than Noma. It was already evening when we spoke, and the moon had not yet risen, wherefore the chief said that he would stay the night in our village. When the first ray of dawn appeared on the horizon, he would go with me to the place where I had said the animals were. Having said this, he left.

I also went to my hut and threw myself on my bed, falling asleep immediately. Suddenly I woke up to the feeling of a weight on my chest. I tried to get up, but something cold touched my throat. I lay down again and looked in front of me. The door of the hut was open and the full moon had just risen, shining like a great ball of fire far above the horizon. In its light I saw the face of the Noma magician. He sat cross-legged on my chest, staring at me with his one eye, and he had a knife in his hand. That knife was the object I had felt on my throat.

“Is that why I advised you, you little brat, to put me aside now?” he hissed in my ear. “And that you should dare to guess and divine after I have failed? Don’t worry, my boy, I will show you right away how such babies are taught. First I will cut out your tongue so that you cannot scream, then I will tear you to pieces inch by inch, and lastly I will cut your arms and legs off your body. In the morning I will tell all the spirits that I treated you so cruelly because you lied. Yes, yes, I will carefully carve the flesh from your bones! I — I —” And he began to grope with his knife the base of my jaw.

“Have mercy, uncle,” I cried, for I was afraid, and the knife stung painfully. “Have mercy, and I will do whatever you wish!”

“Will you do this?” he asked, still tickling my throat with the point of his knife. “Will you go and get that dog’s herd of cattle and drive them to a safe place?” He mentioned a secret valley that few knew of. “If you do it, I will spare your life and give you three cows from the herd. If you refuse or betray me, I will, as my father’s spirit helps me, find some way to kill you!”

“I will gladly grant your request, uncle,” I replied. “Why did you not trust me? If I had known that you wanted to have the animals yourself, I would not have crossed the card. I only did it out of fear that you might lose your gift.”

“You’re not as stubborn as I thought,” he growled. “So get up and do as I say. You’ll be back in a couple of hours after sunrise.”

I arose, thinking all the time whether it would be worth while to attempt to attack him. But I was unarmed, and he had a knife; so that if by chance I should succeed in overcoming him and killing him, it would be said everywhere that I had murdered him, and I would then have a taste of the assegai. I made another plan. I would go and fetch the cattle from the valley which my spirit had advised me to, but I would not drive the animals to that secret hiding place. No; I would drive them by the most direct route to the village, and reveal Noma’s wicked designs in the hearing of my father, the strange chief, and all the people. But I was young then, and I did not know Noma, who had been a magician all his life, and not merely for sport. Oh! he was devilish and cunning—cunning as a jackal and cruel as a lion. He had planted me close by like a young sapling, intending to tend me like a bush whose tops are being pruned. I had now grown tall, threatening to overshadow him, and therefore he wanted to eradicate me from the roots.

I went to the corner of the hut, with Noma keeping an eye on me the whole time, and took my spear and my small shield. Then I stepped out into the bright moonlight and crept quietly on my way. When I got out of the village, I started running, singing the whole way to scare away all the ghosts, my father.

For about an hour I hurried on across the desert until I came to the slope of the hill where the jungle began. It was still very dark under the trees, and I sang louder than before. At last I found the narrow buffalo trail I was looking for, and set out to follow it. I soon came to a clearing illuminated by the moon, and on dropping to my knees to examine the ground I saw that my spirit had not lied; the tracks of the cattle were plainly visible on the ground. I continued my journey happily until I came to a small hollow through which a stream flowed solo. The sound died down to a faint whisper at times, and was heard again with extraordinary clarity. The path trodden by the cattle was now clearly visible, the bushes had been bent and the grass had been trampled to the ground. After a short distance I came upon a pool of water. I knew it at once—my spirit had shown it to me, and there was a drowned ox swimming with its hind leg caught in a branch of a beet. Everything was exactly as I had seen it in my spirit.

I looked around and my eyes immediately discovered something. I saw the faint light of dawn flashing on the horns of a bull. At the same time, one of the bulls blew hard, stood up, and shook the dew off its hide. It looked the size of an elephant in the morning twilight and fog.

I gathered them all together—there were seventeen of them?—and set out before them on their way to the village. The morning broke quickly, and the sun had been up for at least an hour when I came to the point where I should have turned if I wanted to hide the cattle in the place Noma had appointed. But that was not my intention. I had determined to drive the animals into the village and tell everyone that Noma was a thief. I sat down to rest for a moment, for I was tired, and as I sat there I suddenly heard a noise and looked around. A group of men appeared in a nearby village, Noma and the strange chief who owned the cattle at the forefront. I got up and waited in amazement, but as I stood there they ran towards me, screaming and waving their spears.

“There he is!” cried Noma. “There he is, that rascal boy whom I have nurtured to my shame. What did I tell you? Didn’t I tell you he was a thief? Yes, yes! I know you and your tricks, Moposen! Look! He was going to steal the animals! He knew where they were all along, and now he’s driving them to some hiding place. They would have paid off his wife, wouldn’t they, you sly one?” He charged at me with his stick raised, and the strange chieftain, hissing with rage, followed him blindly.

Now I understood everything, my father. An inexpressible rage seized my heart, the world began to spin in my eyes, and it seemed to me as if a red cloth had waved before me. I have always made the same observation when I have had to fight. I roared only one word: “Liar!” and rushed at him. Noma did not stop. He struck me with his staff, but I parried the blow with my little quiver and struck back. Hey! My blow hit, Noma’s skull fell in the path of my club and he fell dead at my feet. I screamed a second time and attacked the chief. He threw his spear at me, but it missed, and in the next blink of an eye I struck straight at his head. He raised his shield for protection, but my well-aimed blow fell, knocking him unconscious to the ground. I do not know, my father, whether he lived or was dead, but as his skull was one of the thickest in the world, I think he lived. While their companions stood there, still bewildered with astonishment, I turned and fled with the speed of the wind. Then they also woke up and went after me, trying to hit me with their spears and catch me, but none could reach me—no one. I ran like the wind, like a deer pursued by dogs I ran, and soon the cries of my pursuers began to die down until at last I was far from their sight and all alone.

III.

THE BOLD RETURN OF THE MOPED.

I threw myself on the grass and panted until I could breathe regularly again; then I set off and hid in a reed in the swamp, where I lay all day, pondering the situation. What was to be done? I was now as defenseless as a jackal driven from its den. If I returned to my tribe, I would certainly be killed, for everyone considered me a thief. I would have to pay with my blood for Noma’s death, which did not please me at all, although I was saddened to death. As I was meditating on this, Chaka came to mind, that boy to whom I had given water long ago. I had heard of him; his name was known everywhere, the grass and the trees of the forest spoke of him, and the very air was full of the glory of his name. His words and my mother’s vision began to come true. With the help of Umtetwa, he had succeeded to the throne of his father, Senzangacona, and had already driven the Amaquabe tribe from their old dwellings; He was at present at war with Zweete, the chief of the Endwande tribe, and had sworn to destroy that tribe so completely that no one could find a trace of it. Now I remembered Chaka’s promise to make me a great man, and that I would grow fat and gain in his shadow. I resolved to get up and go and find him. He might kill me; well, what of it—I’ll go anyway. But my heart compelled me elsewhere. There was only one in the world whom I loved—my sister Baleka. My father had betrothed her to the chief of a neighboring tribe, but I knew that the marriage was very repugnant to my sister. Perhaps she would go with me if I could tell her where I was going. I resolved to try at least.

I waited until dark, when I left my hiding place and crept like a jackal towards the village. I lingered a moment in the vegetable garden and ate some half-ripe corn, for I was very hungry. Then I continued my journey until I reached the village. In front of a hut some men were sitting by a fire, talking. I crept close as quietly as a snake and hid behind a bush. I knew that the men could not see me when I was out of the light, and I wanted to hear what they were saying. As I had guessed, I was talked about and called many names. It was said that I had brought only misfortune to my tribe, since I had killed a great magician like Noma, and the tribesmen of that strange chief also demanded compensation for my attack on him. I heard, moreover, that my father had ordered all the men to be assembled by tomorrow morning to pursue me and kill me wherever I was found. “Ah!” I thought, “You just hunt, but you won’t catch anything.” At that moment the dog lying by the fire began to sniff the air. I had forgotten all about dogs as I approached the village; lack of experience, you see, my father. The dog got up and sniffed from its sniffing and finally began to growl, looking steadily at me, so that I was frightened.

“What is that dog growling about?” said one of the men to his companion. “Go and see.” But the latter was sniffing at the moment and was not willing to get up. “Let the dog go and see for himself,” he snapped; “what is the use of a dog if it cannot catch the thief himself.”

“Shut up then,” said the previous speaker to the dog, who charged forward, barking. Then I saw it: it was Koos, my own dog, and a very good dog. As I lay there motionless, not quite knowing what to do, it smelled me, stopped barking, and running around the bush found me and began to lick my face. “Be quiet, Koos!” I whispered, and it immediately lay down on the ground beside me.

“Where did that dog go?” said the man who had spoken first. “Is it bewitched that it suddenly stops barking and never comes back?”

“Let us see,” said the other, rising with his spear in his hand. I was terribly afraid, for I thought that they would either catch me at once, or I would have to run for my life again. But as I jumped up to make my way, a great black snake appeared between me and the men, and slithered towards the huts. The men jumped aside in fright, and then all followed the snake, saying that it was the dog that had barked. The snake was doubtless my good guardian spirit, which came in this guise to save me.

When they had gone, I crept away, and Koos followed me. At first I intended to kill the dog, lest it should betray me, but when I called it to me to strike it on the head with my club, it sat down before me, wagging its tail, and looking at me as if with a smile; I could not carry out my intention. I thought, “Let it be what it may,” and we continued our journey together. My plan was this: first I resolved to creep to my hut to fetch my spear and my skin, and then I must try to get in touch with my sister Baleka. My hut was probably quite deserted, for I had lived alone, and Noma’s huts were a little way off to the right. I came to the reed-walled enclosure which surrounded the huts. No one was to be seen at the gate, which was not closed with thorn bushes, as usual. The task had been my concern, and now I was gone.

I ordered the dog to lie down outside, and stepping boldly inside, I reached the door of the hut and listened. The hut was empty, and there was not a breath to be heard. I crept in and began to search for my spears, my water jar, and my woolen cloak, which I had made so carefully that I did not want to part with it. I soon found everything. Then I began to search for my skin blanket, and as I groped my hand touched something cold. I was startled, and then I felt more closely. I recognized the face of a man—the face of the dead, Noma, whom I had killed and who had been laid in my hut awaiting burial.

Oh! how I was frightened, for in the dark Noma was worse dead than alive. I was just about to run away when I suddenly heard women’s voices outside the door. I recognized the voices; the speakers were Noma’s two wives, and one said she was going to watch over her husband’s body. Now I was really in for a treat, for before I could do anything the doorway darkened, and from the panting of the fat woman I heard that Noma’s first wife had stooped down and was in the act of forcing her way in. At that moment she was in the hut and threw herself down beside the body in such a position that I could not get to the door, and began to complain of her great grief and curse me. Ah, she did not know that I was listening. I was far behind Noma’s head and fear made my brain work quickly. In the presence of that woman I no longer feared the dead man so much, and remembering what a scoundrel she had been, I decided to let her play one last prank. I put my hands under her shoulders and lifted her to a sitting position. Hearing the movement, the woman made a strange guttural sound.

“Will you shut up, you old scum!” I said, imitating Noma’s voice.

“Can’t you let me be in peace even after I die?”

He fell to the ground helplessly and then started screaming at the top of his lungs.

“What! Do you dare to scream again?” I said again in Noma’s voice, “then I will teach you to be silent.” And I pushed the body on top of him.

Then he fainted, and I do not know whether he ever regained consciousness. Now at least he was silent. I snatched up the blanket—I found out later that it was the best in Noma, made of the finest skins of the Basutos, and worth three oxen—and fled to Koos on my heels.

My father Makedama’s huts were a couple of hundred paces away and I had to get there, because my sister Baleka slept there. I didn’t dare go through the gate, because there was always one man there on guard. I forced my way through the reed fence with my spear and crawled to the hut where Baleka slept with some of her half-sisters. I knew where she usually slept and where her head was. I lay on my side and very carefully began to dig a hole in the wall of the hut. The work went slowly, because the wall was thick, but at last I had dug almost through. I paused, because it occurred to me that Baleka might have changed her sleeping place, and then I would have woken up some other girl. I had already decided to give up my plans and escape alone, when at the same time I heard someone waking up and starting to cry on the other side of the wall. “Ah,” I thought, “that’s Baleka, mourning her brother!” I put my mouth to the hole and whispered:

“Baleka, my sister! Baleka, don’t cry! I, Mopo, am here. Don’t say a word, but get up. Come out and take the leather blanket with you.”

Baleka was a very understanding girl; she did not cry out, as most girls would have done. No; she understood, and after waiting a moment she got up and crept out with the blanket on her arm.

“How are you here, Mopo?” he whispered. “You’ll definitely be killed!”

“Hush!” I whispered, and then told him my whole plan. “Are you coming with me, or are you going to sneak back to the cabin and say goodbye to me?”

After a moment’s thought, he replied: “No, my brother, I will come with you, for I love only you of all our tribe, even though I believe this will be my last journey—that you will take me to my death.”

I didn’t pay much attention to his words at the time, but later they often came to my mind. So we set off together, Koos following, and soon we were on our way across the desert towards the Zulu territory.

IV.

THE ESCAPE OF THE MOBILE AND THE BALEKA.

We wandered all night until the dog was tired, and during the day we hid in a cornfield, for we were afraid that someone would see us. In the afternoon we heard voices and, peering through the corn stalks, we saw a group of my father’s men who were looking for us. They went to a nearby village to ask if we had been seen, after which we did not see them for a long time. At night we wandered on again, but it was probably fate that we met an old woman who looked at us strangely but said nothing. We then traveled day and night, for we knew that the old woman would betray us to our pursuers if she met them, and so she did. On the evening of the third day we came to a cornfield and saw that the corn had been trampled to the ground. Among the broken stalks lay the body of a very old man, who was as full of spear-thrusts as the quills of a hedgehog. We were greatly astonished and hurried on. Then we noticed that the village to which the field belonged had been burned to the ground. We crept closer and—ah! what a sad sight we saw! Later we became accustomed to such sights.

Everywhere lay the dead by the dozen—old men, young men, children, and women with babies at their breasts—there, among the burnt huts, pierced by spears. The ground was red with their blood, and they too looked red in the light of the setting sun. It was as if the great spirit, or Umkulunkulu, had brushed the ground with his bloody hand. Baleka began to cry, tired as she was, the poor girl, and we found only grass and green grains to eat.

“The enemy has been here,” I said, and as I spoke I thought I heard a cry from behind the broken reed fence. I went to look. There lay a young woman; she was badly wounded, but still alive, my father. Near by lay a man dead, and around him others who belonged to another tribe; he had fallen fighting. Before the woman were the bodies of three children, the fourth, who was still very small, resting on her breast. I looked at her, and she cried again, opening her eyes, when she saw me standing beside her with a spear in my hand.

“Kill me quickly!” he said. “Haven’t you tortured me enough?”

I said I was a stranger and I didn’t want to kill him.

“Then bring me some water,” he asked; “there is a spring behind the village.”

I called Baleka to the spot and hurried to the spring with my vessels. There were bodies in the spring, but I pulled them out, and when the water had become a little clearer, I filled my cup and hurried back to the wounded man. He drank and got a little stronger—the water refreshed him.

“What happened here?” I asked.

“The warriors of the Zulu chief Chaka came and destroyed us,” answered the woman. “They attacked us this morning at daybreak, while we were still sleeping in our huts. I woke up to the noise of the battle. I slept beside my husband and children, who are lying there. My husband had a spear and a shield. He was brave. Look, he died like a hero, he killed three of those Zulu devils before he fell himself. Then they rushed upon me and killed my children and beat me until they thought I was dead. When the destruction was complete, they went away. I do not know why they came, but I think it was because our chief did not want to send men to help Chaka against Zweete.”

He fell silent, crying out painfully, and died. My sister wept, and I was moved too. “Ah,” I thought, “the great spirit must be very evil. Otherwise such things could not happen.” I thought so then, my father, but now I think differently. We did not understand the purpose of the great spirit, that was all. I was still young and timid then, but later, as I have already said, I became accustomed to such visions. Nothing could move me, nothing. In Chaka’s days all the streams were mingled with blood—yes, when we went looking for water, we had to always check whether it was clean before we drank. Then people learned to die and did not grumble. What good would it have been? After all, one had to die once. One should not care about death, not a bit, but birth is different. Our birth into the world is a mistake, my father.

We stopped in the village for the night, but we could not sleep, for the spirits of the fallen wandered around us, crying out to one another. It was quite natural that they should do so, the men seeking their wives and the mothers their children. But we feared that they were angry with us, since we had invaded their village, so we pressed ourselves tightly together, trembling with fear. Koos trembled also, and now and then howled plaintively. But the spirits did not seem to notice us, and towards the middle of the night their cries died down.

As the first glimmer of light appeared in the sky we rose, and after a while, winding here and there to avoid the dead, we were soon in the desert again. The road to Chaka was now easy to find, for the warriors and the plundered cattle had trampled the ground into a wide path, and now and then we came across a dead warrior who had been killed because he had been wounded and could not keep up with the crowd. I began to doubt whether it was at all wise to go to Chaka, for after all we had seen I began to fear that he would kill us. But as we had nowhere to go, I said we would continue our journey until something happened.

Our strength was beginning to fail, and Baleka said that it would be better for us to throw ourselves on the ground and die to get rid of all our troubles. We sat down on the edge of a spring. I did not want to die yet, even if that would have been the best thing, as Baleka said. While we were sitting there, Koos disappeared into a nearby bush, and at the same time I saw him jump at someone and heard a noise. I hurried to see — the dog had mated a wild goat as big as himself, which had been sleeping in the bush. I pierced the animal with my spear and cried out with joy, because now we had something to eat.

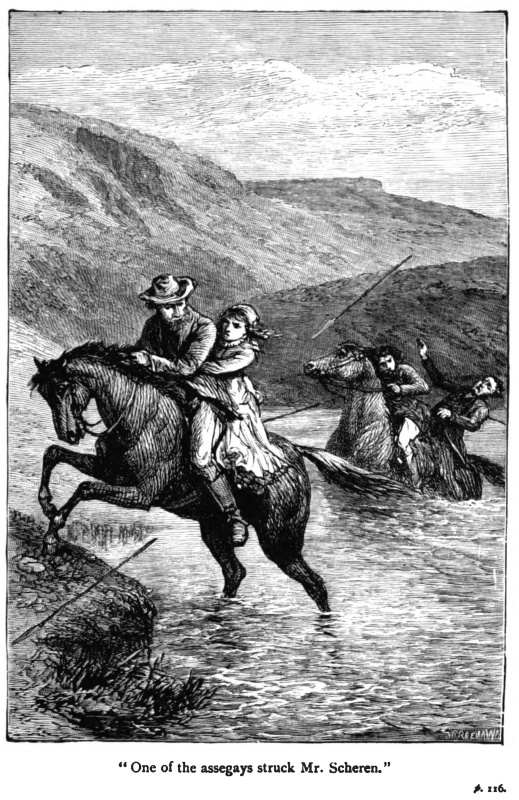

I skinned the beast and cut long slices from its thigh, which we washed in the spring and ate raw, for we had no fire to cook our food with. Raw meat is indeed disgusting to eat, but we were so hungry that we cared nothing for anything, and the meat refreshed us. Having eaten as much as we could, we rose and washed in the spring, but when we were almost done, Baleka suddenly looked up and cried out in terror. For in front of us, on the top of a hill about ten spear-throws away, were six armed men of my own tribe—the children of my father Makedama—who were still pursuing us to capture or kill us. They saw us—cryed and charged toward us. We sprang up and dashed into the desert—running like deer, for fear stiffened our legs.

There were no obstacles in front of us, and the land sloped gently towards the Umfolozi River, which wound across the plain like a great and glittering serpent. On the other side the land began to rise again, and we did not know what lay beyond the banks, but we thought that the Chaka villages were there. We ran towards the river—where else, and the warriors came after us. They came nearer and nearer; they were in full force and furious at being so far from home. We ran for our lives, but they only came nearer. We reached the river’s edge, the river was in flood and fearfully wide. Above was a strong gorge, where the water surged in foamy eddies created by invisible quarries; below was a rapid whose rush no one could have survived; here and there was a calm backwater, but with a strong current.

“Ah, my brother, what do we do now?” panted Baleka.

“There is no other choice but to either fall under the spears of our tribesmen, or try to cross the river,” I replied.

“It is easier to drown than to die from spears,” said Baleka.

“Okay. At least we can swim and may the spirits of our fathers come to our aid.”

I took him to the head of the backwater, and having thrown our blankets and all our things on the shore—except my spear, which I took between my teeth—we plunged into the water and waded as far as we could. The water soon reached our chests, and after taking a few steps more we began to swim towards the other shore, Koos in front of us.

At the same time, warriors also appeared on the scene.

“Ah, you rascals!” cried one, “are you going to swim? Just swim, but you will surely drown, and if you do not drown, we will kill you, for we know the ford, and we will catch you! We will catch you, even if we have to run after you to the ends of the earth.” And he threw us at his spear, which passed between us, flashing like lightning.

We swam with strong strokes all the time and got into the current. It rushed us down, but we kept going, for we were both good swimmers. If we could get to the shore before we were carried away by the rapids, we would be safe; if not—then good night!

We were already close to the shore, but the foam jets were also close. We struggled and fought for our lives. Baleka was a brave girl and swam bravely, but the current pressed her beneath me and I could not help her in any way. I leaned my feet against a rock and looked around. There she was, eight steps away from the roaring whirlpools. I could do nothing. I was too powerless and it seemed to me that she must perish. But then Koos came to the rescue.

It swam to him and then turned against the current, barking a couple of times, and Baleka grabbed its tail with his right hand. He used his legs and his left hand and they both approached slowly—very slowly. I held out the shaft of my spear towards them and Baleka grabbed it with his left hand. His legs were still in the water, but I pulled and Koos pulled and finally we got him into the water and then onto dry land, where he sank, panting for breath.

When the warriors on the other bank saw that we had crossed, they shouted furiously and rushed down.

“Get up, Baleka!” I said. “The warriors have gone looking for a ford.”

“Ah, let me die!” he replied.

But I forced him to rise, and in a moment he was breathing regularly, and we hurried as fast as we could up the long slope. After a little over three hours we came to a plain and saw a large village far ahead.

“Take heart,” I said. “Look, Chaka lives there.”

“Yes, my brother,” he replied, “but what fate awaits us there?

Behind us and before us is death—we are in the jaws of death.”

We soon reached the road that led from the ford straight to the village, and along which Chaka’s warriors had passed. We hurried on until at last we were only half an hour’s journey from the village. We looked behind us, and lo! our pursuers were after us again—five in all—for one had drowned in trying to cross the river.

We ran again, but we were already exhausted, and the warriors were coming closer and closer. Then the dog came to my mind. Koos was angry and would attack anyone at my command. I called him to me and, although I knew that he would not survive the game alive, I decided to sacrifice him. I pointed at the men, and the dog rushed at them like an arrow, growling and with his ears pricked up. They tried to hit him with their clubs and spears, but he raged around them like a horned spirit, biting furiously and not letting the group move forward. Finally, one of the warriors managed to hit him with his spear, but at the same time the dog also rushed at the warrior’s throat, and both fell. A furious fight followed and only ended when both were dead. Ah, that was a dog! You don’t see such things anymore in this day and age. His father was a Boer dog, the first of its kind in this country. Once it had even killed a leopard all by itself. Well, my dog Koos died fighting to the last.

We had been running all the time, and the village gate was only a couple of hundred paces away. Something was going on inside; we could tell by the noise and the clouds of dust that were rising high. Our four remaining pursuers were on our heels again, having left their dying comrade to his fate. I knew they would catch up with us before we could get through the gate, for Baleka could only walk slowly now. A thought then crossed my mind. I had lured her with me, and I must save her by any means necessary. Even if she got into the village alone, Chaka would not kill a young and beautiful girl like her.

“Run, Baleka, run!” I said, lagging behind. He was almost blind with fatigue and terror, and staggered toward the gate, not perceiving my purpose. But I sat up to breathe, for I must fight four to the death. My heart beat to burst, and the blood roared in my ears, but as the men drew nearer, I rose, spear in hand—again I saw the red flickering before my eyes, and my fear vanished.

The men came in pairs, running about a javelin’s throw apart, but one of the first pair was about six paces ahead of the other. He charged at me, roaring, spear and shield raised. I had no shield, only a spear, but I was on my guard and he was arrogant. I waited until he drew his spear back to strike, but at the same time I dropped to my knees and struck with all my strength upwards, just below the edge of his shield. He struck too, but over me, the spearhead only slightly scraping my shoulder—you see—the scar is still visible to this day. And my spear? Ah, it hit the spot, pierced through the middle. He fell and was covered in a cloud of dust on the ground as he struggled. But now I was unarmed, for my light throwing spear broke as he fell, and I had only a short piece of the shaft in my hand. And the other warrior was already upon me! He looked as big as a forest tree as I looked up, and I lost hope, I felt I was dying, and the abysses of darkness seemed to be opening. I threw myself on my hands and knees and rolled with all my weight against the feet of my opponent, with the result that he fell facedown on the ground, and before his hands had touched the ground I was on my feet. The spear had slipped from his hand. I snatched it, and as he began to rise I struck it into his back. All this happened in the twinkling of an eye, my father, and in the same twinkling of an eye he was dead. Then I hastened on my way, not daring to wait for the others, for I was exhausted and my courage had gone.

About a hundred paces away Baleka staggered forward with his arms spread out like a man who has drunk too much beer, and when I caught up with him he was about forty paces from the gate. But then his strength failed him. He fell unconscious to the ground, and I was left standing beside him, and would have been killed had not the permission decreed otherwise. After lingering a moment with their dead comrades, the two remaining warriors rushed at me, mad with rage. But at that moment the gate opened, and a group of warriors rushed out, dragging the prisoner with them. Behind them walked a burly man with a leopard skin on his shoulders, laughing, and followed by five or six advisers, all of whom had a shiny ring around their heads. A group of warriors brought up the rear.

The warriors immediately realized that a killing was in progress and rushed to the scene just as our pursuers caught up with us.

“Who are you who dare to kill at the gate of Elephant’s dwelling?” cried the warriors. “Here only Elephant has the right to kill!”

“We are men of Makedama,” answered our pursuers, “and we are pursuing these evildoers, who have done much evil and even murder in our home. Look! They have just killed two of our comrades, and others are lying lifeless along the road. Allow us to kill them.”

“Ask Elephant,” replied the warrior, “and at the same time ask that you not be killed.”

The burly chief heard the words and stepped closer, noticing the blood. He was unusually tall and well-built, although he was still very young. He was a head taller than any of the others, and his chest was as wide as two ordinary man’s chests put together. His face was beautiful and fierce, and when he got angry, his eyes sparkled like a firewood plucked from a campfire.

“Who are these who dare to raise dust before my gates?” he asked, frowning.

“O Chaka, O Elephant!” replied the leader of the troop, bowing almost to the ground, “these strange warriors say that they are evildoers whom they have been sent to kill.”

“Good!” he said. “Let the evildoers be killed!”

“We thank you, O great chief!” said my tribesmen who had come to kill us.

“You heard my words,” he replied, and added, turning to the leader of the warriors: “When they have slain the evildoers, gouge out their eyes and turn them to the desert to seek their homes, because they have dared to raise their spears at the gates of the Zulus. Let your praise resound, my child!” And he burst out laughing as the warriors murmured: “Oh! he is wise, he is great, and his judgment is bright and terrible as the sun!”

But my people cried out in fear, for they did not ask for this kind of justice.

“Cut their tongues too,” said Chaka. “What? Must the Zulu put up with all that noise? No way! It frightens the cattle and makes the cows give birth prematurely. Go, you black rascals! There’s a girl there. She’s unconscious and helpless. Kill her. What? Are you hesitating? Well, if you want to think about it, I’ll give you time to think. Grease those men with honey and tie them up in an anthill; tomorrow they’ll know what they want. But first kill those jackals,” and he pointed to me and Baleka. “They look tired and probably want to rest.”

Until then I had been silent, but now I spoke, for the warriors were approaching.

“Oh Chaka!” I exclaimed. “I am Mopo and this is my sister Baleka.”

I sighed and everyone present burst out laughing.

“Good morning, Mopo and your sister Baleka,” said Chaka cruelly. “Good morning, Mopo and Baleka, and—good night too!”

“Oh Chaka!” I interrupted. “I am Mopo, son of Makedama, chief of the Langen tribe, the same one who once gave you water to drink long ago, when we were both still small. Then you asked me to come to you when you had grown up, and you swore to protect me and do me no harm. I have come with my sister, and now I ask you not to break the promise you made long ago.”

As I spoke, Chaka’s expression changed, and he listened intently, like a man with his hand behind his ear. “That is not a lie,” he said then. “Welcome, Mopo! You may be a dog in my hut and eat from my hand. But I did not mention your sister. Why should I not let her be killed, when I swore to destroy your whole tribe except you?”

“Because she is too beautiful to be killed, O chief!” I answered boldly, “and because I love her. Grant me the grace to spare her.”

“Turn the girl over,” said Chaka. And the warriors did so, revealing her face.

“You have not lied this time either, son of Makedama,” said the chief. “I grant your request. Let her also lie under my protection and be numbered among my sisters. Now tell your story, but speak the truth.”

I sat down and told him everything, and he never tired of listening. When I had finished, he only said that he was sorry that my dog Koos had died. If the dog had still lived, he would have placed it on the crest of my father Makedama’s hut, and made it the chief of the Langen tribe.

Then he said to the leader of the warriors: “I take back my word. Let those scoundrels not be mutilated. Let one die and the other go his way. Here,” he pointed to the man whom the warriors had dragged out of the gate, “here, Mopo, is a man who has shown himself to be a coward. Yesterday, on my orders, a village of outlaws was destroyed—perhaps you both saw it as you passed by. This one and three others harassed a warrior who was defending his wife and children. This dog, afraid to meet him face to face, killed him with a javelin, and then killed his wife. Never mind, but he should have fought like a man to face. Now I will grant him that honor. He must fight to the death with one of those scoundrels of yours.” And he pointed with his javelin at my father’s men. “He who survives will be pursued, as you have been pursued. I will send the other pig home to take my greetings to your tribe. Choose, children of Makedama, which of you will live.”

Now it happened that these men were brothers and loved each other, and both were willing to die for each other. Therefore they both came forward, saying that they wanted to fight the Zulu.

“What, do pigs have any sense of honor?” said Chaka. “Then I will decide the matter myself. Do you see this spear? I will throw it into the air: if it falls on its point, the taller man is free, and if it falls on its shaft, the shorter one will live. That’s it!” And he threw the little spear into the air, making it spin wildly. Everyone watched as it spun and fell. The point touched the ground first.

“Come here,” said Chaka, farther from the brothers. “Hurry back to Makedama and tell him thus: ‘Thus says Chaka, the lion of Zulu-ka-Malandela. Years ago your tribe refused to give me milk. Today your son Mopo’s dog howls on the roof of your hut.’ Go!”

The man turned to shake his brother’s hand, looked at me with a frown, and left with those ominous greetings.

Then Chaka turned to the Zulu and my last assailant and ordered them to fight. After saluting the chief with shrill cries, they charged each other, and a fierce battle began, which ended in my tribe defeating the Zulu. But as soon as he had had a little time to catch his breath, he had to run for his life, followed by five chosen runners.

But the man overcame them too; he meandered here and there, leaving his pursuers behind him, and escaped. Chaka was not at all angry at the result, and I think he had ordered his men to run slowly. There was only one good quality in Chaka’s cruel heart: he always wanted to save the life of a brave man, if it were possible without his having to break his word. For my part, I was glad that my tribe had killed the man who had killed the children of the dying woman we met in the village across the river.

V.

THE MOPED BECOME THE KING’S DOCTOR.

Thus, my father, I, Mopo, and my sister Baleka, came to Chaka, the Zulu chieftain. I have related these incidents with such detail that they form an inseparable part of my story of the fate of my people. We shall see that as a direct consequence of these incidents, Umslopogaas Bulalio, the butcher, and Nada the beauty, whose lemmentari is also included in my story, were born into the world—they were like a seed from which a great tree grows. For Nada was my daughter, and Umslopogaas, though few knew it, was none other than Chaka’s son, born to my sister Baleka.

When Baleka had recovered from the exhaustion of our flight and her beauty had returned to its former state, Chaka took her as his wife—his “sister,” as he called them. He took me as his physician, his izinyanga , of whom there were already a large number, and my skill pleased him so much that I finally became his chief physician. This was already a great position, in which I accumulated much cattle and wives over the years, but it was also a dangerous one. When I arose in the morning healthy and vigorous, I never knew whether I would lie down in the evening bloody and stiff.

Chaka killed many doctors; however well they did their work, they were killed in the end. It often happened that the king felt sick or depressed, and those bastards who had cured him got a taste of the spear or torture! But I always survived by my skill, and then I was also protected by the oath that Chaka had sworn to me as a child. And things finally developed to the point that I followed the king everywhere. My hut was near his hut, I sat behind him in negotiations, and in battle I was always close to him.

Ah, those battles—those battles! We knew how to fight then, my father! Thousands of vultures and packs of hyenas could follow our regiments then, and not one had to go hungry. I can never forget the first battle in which I stood beside Chaka. It was just after he had built his great city on the south bank of the Umhlatuze. A chief named Zwide was then harassing his rival Chaka for the third time, who was arrayed against him with ten full regiments, armed for the first time with short javelins.

The position was as follows: on a long, low slope in front of us were Zwide’s regiments, seventeen in number, the whole horizon black with warriors, and their crests filled the air like snow. We were also on the slope of a hill, and between us was a valley through which a small river flowed. All night long the fires burned across the valley, and the warriors’ song echoed from the slopes, and when the gray morning dawned and the oxen began to shoot, the regiments rose from their spear beds; the warriors jumped up and shook the dew from their hair and shields—yes! they rose! they were ready for a joyful death. Regiment after regiment formed for battle.

Those countless spears, which were like stars in the sky, formed a huge belt, and like stars they sparkled and flashed. The morning breeze swayed and caressed them, and the warriors’ crests swayed in the wind like a waving field of grain, warriors who were ripe for the spear. The sun rose from behind the hill and cast its reddish light on the red kiwis, reddening the battlefield, and the chieftains’ crests were as if dipped in the blood of the sky. They knew what it meant, they saw that death foretold, but ah, they only laughed with joy at the thought of the battle that was about to begin. What about death? Wasn’t it sweet to die under the blows of spears? What about death? Wasn’t it lovely to die before the king? Victory is won by death. In the evening victory will be their bride, and ah, her bosom is charming.

Listen! The war song, ingomo , which with its power intoxicates the minds of men, begins to echo from the left and rolls from regiment to regiment, growing louder and louder until it rumbles like thunder:

Ready to die, we are the children of our king,

You are also one of us!

We are Zulus, We are the children of lions,

What! Are you trembling?

At the same time Chaka was seen walking, surveying the ranks, followed by his chiefs, his superiors, and myself. He resembled a great elk in his walk, and his gaze foretold death, as he sniffed the air like a deer scenting a great kill. He raised his spear, and silence fell everywhere, only the echo of the song still echoed on the slopes.

“Where are Zwide’s children?” he shouted, his voice echoing like the bellowing of a bull.

“There, father,” replied the regiments, and every spear pointed across the valley.

“They won’t come,” he shouted again. “Must we sit here and wait until we are old?”

“No, father,” was the reply. “Let us attack!”

“Let the Umkandhlun regiment advance!” he shouted for the third time, and at the same time the black shields of the Umkandhlun regiment rushed from the ranks.

“Go, my children!” cried Chaka. “The enemy is there. Go and do not come back!”

“We hear, father!” the warriors answered in unison, charging down the slope like a vast herd of steel-horned wild beasts.

They charged across the river, and Zwide’s troops woke up. Shouts rose from the ranks, and rows of gleaming spearheads flashed.

Oh! they are coming! Oh, the armies have struck together! Hear the clash of shields!

Hear the din of battle!

The ranks are tottering. Umkandhlu’s regiment is retreating—running away! The warriors are rushing back across the river—half the regiment has fallen. A furious shout rises from our ranks, but Chaka only smiles.

“Open ranks! Open ranks!” he shouts. “Order for the girls of Umkandhl!” And the warriors go behind our front with downcast eyes.

Now he whispers something to the nobles. They hurry away, say a word to General Menziva and the chiefs, and at the same time two regiments charge straight down the slope, two regiments rush to the right and two to the left. But Chaka remains on the hill with the three remaining regiments. Again the shields clash against each other, thundering. Ah! they are brave: they fight and do not flee. Regiment after regiment attacks them, but they do not retreat. Hundreds, thousands of them fall, but not a single warrior shows his back to the enemy, and each of our fallen ones costs the enemy a couple of men. Wow! my father, those regiments were destroyed to the last man. Their warriors were only young men, it is true, but they were Chaka’s children. Menziva was buried under the bodies of his warriors. There are no such men any more. They are all dead.

But Chaka still waits. He looks north and south. And look! Spears flash between the trees. Our regiments are charging the enemy’s posts. They kill and are killed, but Zwide’s warriors are brave and numerous, and we are about to be defeated.

Then Chaka uttered the decisive word. The chiefs listened and the warriors cocked their heads to hear.

At last the cry has resounded: ” Forward, children of the Zulu people !”

Our war cry resounds like thunder, the ground trembles with the tread of our feet, spears flash, spears bend, and like a storm cloud, like a river rushing over its banks, we rush down the slope against the enemy, who is arrayed to meet us. At the same time the river is behind us, and our wounded comrades rise up and wave their hands at us. We trample them under our feet. What about them? After all, they can no longer fight. Then Zwide’s warriors rush to greet us and we strike together like two oxen. Oh! my father, I no longer know what is happening around me. Everything turns red. That fight! That fight! We sweep the enemy out of our way, and when it is done, they are no longer visible, but the slope is black and red. A few managed to escape. We went over them like a raging fire; we destroyed them. After a while we stopped to see where the enemy had gone. All were dead. Zwide’s army was gone. Then we formed our lines. Ten regiments had seen the sun rise, three regiments had seen the sun set; the rest had gone where no sun shines.

Such were our battles in the days of Chaka!

You ask what happened to the Umkandhlun regiment that escaped. Let me tell you. When we got home, Chaka ordered an inspection of that regiment and spoke to the warriors gently, very gently. He thanked them for their service and said it was only natural that the “girls” would faint at the sight of blood and flee to their huts for safety. But he had not asked them to come back and yet they had come! What was he to do now? And he covered his face with the edge of his cloak. Then the warriors killed them all—there were a couple of thousand men—killed them with mockery and insults.

That’s how we treated cowards then, my father. And after that one Zulu answered five men of another tribe. If ten enemies came against him, he would not flee. “Fight and fall, but do not flee,” was our motto. And it never happened again during Chaka’s lifetime that a defeated regiment entered the gates of the king’s city.

This battle was but one of many. Every month a new army set out to dip their spears, returning with fewer ranks, but bringing with them news of victory and an immense amount of cattle. Tribe after tribe was subdued, and new regiments were formed from those that were spared from destruction, so that, though thousands fell every month, our army only grew. Soon all the other chiefs had fallen. Umsuduka and Mancengeza fell. Umzilikazi fled north, and Matiwane was utterly defeated. Then we invaded this country of Natal. When we came, its population could not be counted. When we left, we might have met a soul here, hidden in some hiding place, but that was all. Everyone was killed—men, women, and children—and the whole country was left desolate. Then came the turn of U’Faku, the chief of the Amapondo tribe. Ah, where is U’Faku now?

And so the war continued until even the Zulus grew tired of it and even the sharpest spear became dull.

VI.

THE BIRTH OF UMSLOPOGAS.

Chaka’s main principle was that he did not want children, even though he had many wives. Any children his “sisters” bore him were killed immediately.

“What good would it do me, Mopo,” he said to me, “to raise children who would kill me when they grew up? I am called a tyrant. Tell me, how do chiefs who are called tyrants die? Killed by their descendants, is that right? No, Mopo, I will take care of my life, and when I have gone to my fathers, let me take my strongest place and my power!”

Now it happened that a short time after Chaka had spoken to me thus, the time came for my sister, Balekan, who was now the king’s wife, to give birth, and on the same day my wife Macropha gave birth to twins, and eight days before my other wife, Anadi, had given me a son. You ask, my father, how I came to be married, when Chaka had forbidden all warriors to marry until they had reached middle age and put a ring around their heads as a sign of adulthood. When I was a doctor, he made an exception for me, saying that it was good for a doctor to know the diseases of women and to know how to cure their bad natures if necessary. As if it were possible, my father!

When the king heard that Baleka was sick, he did not kill her at once, for he loved Baleka a little, but sent for me, ordering me to take care of my sister and, after the birth, to bring the child’s body to him, as was the custom, so that he might ascertain whether the child was really dead. I bowed down before him and went with a heavy heart to fulfill his command. After all, Baleka was my sister and her child was of the same blood as I! But it had to be so, for Chaka’s whisper was like the roar of other kings, and if we dared to disobey, all our tribesmen would answer for it with their lives. It was better, therefore, to let one child die than for all to be eaten by jackals. I soon arrived at the residence of the king’s wives, called the emposeni , and mentioned the king’s command to the guards, who let me through the gate. I entered Baleka’s hut. There were other wives of the king there, but when they saw me they immediately got up and left, for it would have been against the law to remain in the tent after I had come in. Then I was left alone with my sister.

She lay quietly and didn’t say anything, but I could see from the heaving of her chest that she was crying.

“Calm down, my little one,” I said at last; “your pain will soon pass.”

“No,” she answered, raising her hand, “now it is only beginning. Oh, you cruel man! I know why you came. You came to kill the child I will bear.”

“The king’s command, wife!”

“The king’s command, yes, and what is the king’s command? Then have I no say in the matter?”

“The child is the king’s, wife.”

“The child is the king’s, but mine too. Must it then be that my little one be torn from my breasts and strangled? And would you do this, Mopo? Have I not always loved you, Mopo? Did I not flee with you from our tribe when you feared our father’s vengeance? Do you know that a couple of months ago the king was furious with you when he felt ill and would have killed you if I had not spoken up for you and reminded him of his oath? And this is how you thank me now: you will kill my child, my firstborn!”

“By the king’s command, wife,” I said fiercely, but my heart was about to burst.

Then Baleka said nothing more, but turned to the wall, crying and moaning heartbreakingly.

As she wept, I heard footsteps outside the hut, and at the same moment the doorway darkened; a woman entered. I turned to see who it was, and threw myself on the ground, for before me stood Unandi, the king’s mother, who was called the “Mother of Heaven,” the same woman to whom my mother had refused to give milk.

“Hail, O Mother of Heaven!” I said.

“Hello to you, Mopo,” he replied. “Tell me, why is Baleka crying?

Is it because it is his turn to suffer the pain of a woman?”

“Ask him himself, O great lady,” I replied.

Then said Baleka: “I weep, O mother of the king, because that man who is my brother has come by the command of him who is my lord and your son to murder him whom I bear. Speak for me, O you whose breasts have nursed! Your son was not killed at birth.”

“Perhaps it would have been better if he had been killed, Baleka,” replied

Unandi; “then many a man who is dead would still be alive.”

“At least as a child he was kind and gentle, so that you could love him, Zulu mother.”

“No, Baleka! When I was little, he bit my breasts and tore my hair; he was already like that then.”

“But his child may be different. Mother of Heaven! Think, you have not a single grandson to rejoice in your old age. Do you want to see your family tree completely wither? The king, our lord, is constantly at war. He may fall. What then?”

“The Senzangacona family tree is turning green after all. After all, the king has brothers!”

“They are not your blood, mother. What? Don’t you hear, don’t you understand my words? Then I appeal to your womanly heart as a woman. Save my child or kill me with my child!”

Then Unand’s heart softened and tears of emotion welled up in his eyes.

“Could it somehow happen, Mopo?” he asked. “The king must see the dead child, and if he begins to suspect some treachery, you know Chaka’s heart and you know where we shall rest tomorrow. Even the reeds have ears here.”

“Are there not other newborn children in the Zulu country?” asked Baleka, in a whispering voice that sounded like the hissing of a snake. “Listen, Mopo! Is not your wife now in the same predicament? Listen, Mother of Heaven, and listen, my brother, to what I say. Do not trifle with me in this matter. I will save my child or destroy you both. I will tell the king that you both came to me and told me of the conspiracy you had planned to save the child and kill the king. Now complain and I will hurry!”

He collapsed on his bed and we looked at each other in silence. Then

Unandi said:

“Give me your hand, Mopo, and swear that you will not reveal this secret of ours to any mortal, which oath I swear to you. Perhaps one day the day will dawn when that child, who has not yet seen the light of day, will rule as king of the Zulu country, and then he will repay your loyalty by making you the mightiest man in the land, the king’s pet, and the king’s advisor. But if you break your oath, remember that I will not die alone!”

“I swear, O Mother of Heaven,” I replied.

“Okay, son of Makedama.”

“Very well, my brother,” said Baleka. “Go now and do quickly what you must do, for the hour of my affliction is approaching. Go, knowing that I will be merciless if you do not succeed; I will put you to death, even at the risk of my own life!”

I left. “Where are you going?” asked the gatekeeper.

“To get my medicines, king’s man,” I replied.

So I said, but oh—my heart was heavy and I had decided—to flee far from Zululand. I could not and dared not do what was required of me. What! Must I kill my own child to save Baleka’s little one, and must I be stubborn to the king by saving a child condemned to darkness to behold the brightness of the sun? No, I decided to flee, to leave everything and hide among some distant tribe, where I could begin to live again. I could not be here; in Chaka’s shadow only death lurked.

I arrived at my huts and heard that Macropha had given birth to twins. I ordered everyone to leave except my second wife, Anad, who had given me a son eight days earlier. One of the twins—a boy—had been born dead. The other was a girl, the same one who was later called Nada the Beauty and Nada the Lily. An idea flashed through my mind. I had found a way to escape.

“Give me the boy,” I said to Anad. “He is not dead. I will take him outside the city and bring him back to life by my means.”

“No need—the child is dead,” said Anadi.

“Son here, wife!” I snapped, and she handed me the body, which I fitted into my medicine hat wrapped in a mat braided from grass.

“Don’t let anyone in until I return, and don’t say a word about this seemingly dead child. If you let anyone in or say a word, my medicine won’t work and the child will indeed die.”

I left, leaving the women in astonishment, for we are not accustomed to keeping such a close count of the welfare of one twin, as long as the other survives. I ran quickly to the gate of the emposen .

“I’m bringing medicine, king’s men!” I shouted to the guards.

“Come in,” was the reply.

I went through the gate and hurried to Baleka’s hut, where Unandi and my sister were alone.

“A child has been born,” said the king’s mother. “Behold, Mopo, the son of Makedama.”

I bent down to look and saw a tall boy with large black eyes just like King Chaka’s. Unandi looked at me and whispered, “Where is he?”