CHARLES H. EDEN

A Tale of the Land of the Tsulu and Cetewayo

Letter

CHARLES H. EDEN

Finnish version.

Helsinki, Finnish Literature Society printing house, 1880.

CONTENT:

1. My Plant Brother

2. The King’s Messenger

3. The Autocrat in His Council

4. Warned and Equipped

5. In the Camp

6. Unfortunate Exercise

7. After the Tragedy

8. Expression in the Haystacks

9. Nomteba, the Witch-Wife

10. Midnight Guest

11. Crossing the Border

12. Woe to you, my brother

Chapter 1.

My plant brother.

“Kuta,[1] wake up; the eastern sky is red and the day is about to break.”

I had been sleeping peacefully and soberly in that deep, undisturbed sleep which always follows hard work and simple food, when the above words fell upon my ears, confirmed by a slight touch upon my right shoulder. In a twinkling I was on my feet, and almost inevitably stretched out my hand to where my loaded gun hung by the bedside; for I was in a semi-civilized country of the woods, where a man’s life is in the right hand of every man, and a sudden noise may often be interpreted as a summons to battle rather than a summons to a feast. A low, bright laugh, however, revived my dulled senses, and, stretching out my arm for a necessary article of clothing which lay on a chair by my bed, I began to dress myself, before following the person who had so pitilessly interrupted my sweet slumber to the pool of water, where we intended to take our sober morning bath.

“Does the day promise anything good?” I asked, as I searched haphazardly in the semi-darkness for a lost towel.

“In half an hour the dew will have evaporated from the grass and the cattle are out in the hay. Hurry, Kuta, hurry!” And bending down to the ground, my companion handed me the lost garment, which his sharp eye had easily found.

The first principles of health care clearly state that a morning bath is a more powerful health-preserver than all other doctorings; but as I remembered with longing my warm, comfortable bed, I regretted for a moment the imprudence of which I had made myself guilty the night before, when I asked my friend to wake me a little earlier than absolutely necessary. However that was the case, no doubt was of any help, and so I trotted out into the open air, where Ula[2] had gone before me, and followed her down to the pond, whose lovely glimmer amply rewarded the interruption of my sleep.

The sun rose as we were about to decide on our attire, and another day dawned—a day that promised to be no more rich in excellent incidents than the one that had preceded it. I stood waiting for my companion, who, having shaken off the drops of water from his lithe body with a long and skillful shake, like a fluffy poodle, was now hastily dabbing himself from head to toe with some oily substance, which he poured from a small bottle, which, for want of a better place to keep it, hung gracefully dangling from his right earlobe. The smooth surface of the pond was a mirror, into which he gazed with inexpressible satisfaction, arranging his body in comfortable positions, and evidently greatly delighted with the brilliant reflection which the water reflected; for my friend was a joker, a real ladies’ man among his people.

The word friend , dear reader, is not uttered thoughtlessly, but in the fullest sense that can be applied to the title. Ula, the exiled Tsululai chief, was my friend, and one of whom any man on the face of God’s created earth might have been proud. And, to top it all, we were more than friends, we were brothers, for we had both hung on the same breast, we had both drawn our nourishment from the same source: his mother had been my suckler; Ula and I were plant brothers.

A few words will explain how things had come to be. My parents died soon after my birth, leaving me, a poor little thing, only a few months old. I was by no means a water-waste in the ordinary sense, and a good-natured new-builder, whom my guardians had appointed to look after the farmlands during my infancy, generously consented to take me into his care; and after a Tsulu wet nurse had been procured, I was taken away to the Natal frontier, on the banks of the Buffalo River, in which part of the settlement my new-builder’s house was situated. There I grew up more like a little bushman than a Christian, and in all other respects, except my white complexion, it was impossible to distinguish me from the negro rascals who were my companions. At the age of ten I was sent to England, because my guardians had at last awakened some sense of responsibility; and I still remember the sorrow with which I threw away my bush life, to submit to the tedious discipline of propriety. What heart-rending pain, both mental and physical, was the exercise of the first rudiments of learning; how the clothes which bound me, chafed my calves, and hindered my freedom of movement; how mercilessly my school-fellows teased me, when a certain scoundrel among them, who had read Gordon Cumming, soon christened me a “Bechuan bushman,” which name I was allowed to keep as long as I remained with Dr. ——s. How lonely and miserable it seemed to be thrown into the midst of a new people, into the company of strange companions, who laughed at me, made fun of me, made my life miserable; and how I longed to have my former playmate and brother, Ula, with me, under the tender care with which his mother would have cared for both her children. At that time I thought my guardians cruel and wicked, depriving me of all that I loved; now I see that they were only doing their duty. A few more years in such an untamed state of decay, and my wild nature would have been so deeply rooted that it would never have been able to leave.

While I was in England, strange news reached me from Natal concerning my foster-mother, Landela. That she was the widow of a great Tsululais chief, who had been falsely accused of witchcraft and cruelly put to death by the tyrant Panda, I had heard in my childhood, but at that age I had given the matter very little thought. My ^olijoja now informed me in his letter that the present ruler, Cetewayo, had revoked the proclamation of exile to which my nurse had been subjected, recalled both her and my half-brother Ula to his kraal[3], and promised to place the latter in his rights among the chiefs of the tribe as soon as he had attained the age of manhood. “This circumstance,” said my guardian, “will be of great advantage to you on your return to the colony. Rumor has it that your former partner is in great favor with the king, and probably with his help, and your thorough knowledge of the Tsulu language, you will have an opportunity, after selling your present farm, to settle somewhere in that lovely grassland country which borders the Transvaal, and which even the Boers, considering its proximity to the warlike Tsulu, rather dread. Ula’s influence will guarantee you a favorable reception at the royal kraal.”

Three years before the day on which this story begins, when I had come of age and had legally taken possession of my hereditary estate of several thousand acres—a vast tract of land on paper, but very small in terms of its annual income—I sailed again to Natal, and having met a countryman who agreed to buy my estate, I gladly accepted his terms, and the bargain having been made, I rose to go and greet my cousin, who was then staying at the capital of Cetewayo, the so-called Great Kraal. I will not go into the details of the journey, for later we shall often meet the Tsululais chief, and unnecessary digressions do not interest me at all. Suffice it to say that both Landela and her sons received me with the most cordial enthusiasm. The latter had grown into a noble-looking warrior, though he had not yet attained that mark of rank which in the land of the Tsulu distinguishes “men” from boys, he was not yet allowed to keep his head shaved in a circle around the crown. Cetewayo also condescended to treat me kindly, assuring me that I should fear no disturbance, even if I settled in that disputed territory north of the Pongola stream. He also gave Ula permission to accompany me in my search for good cattle and agricultural lands.

Our journey was by no means without adventure, though I will not here go into them; the proper purpose is served by mentioning that in the nearby Eloya Mountains we found a tract of land wonderfully suited both for cultivation and for stock-raising, and of which I now had possession. Our main business having been accomplished, Ula returned to Umpangeni, the King’s Kraal, while I went to some of the Transvaal outposts to procure myself cattle and other necessities. I may here remark that, though my sojourn in England had almost erased the Tsulu language from my memory, my skill in it returned as if by magic when I was again among that people, and by the time Ula left me to return to the Great Kraal, I could again speak Tsulu as fluently as I could speak English.

But while I was living in the new settlements of the hospitable Boers, I found that my knowledge of agriculture was too limited to assure me of success if I ventured to undertake farming on my own. Great experience was necessary if I was to bring cattle-raising to a profitable stock, and this experience was yet to be acquired; and so I went to apprentice myself to a good-natured old Dutchman, my nearest neighbour, to reside under his roof until I had learned the secrets of the occupation to which I intended to devote myself.

Among good old Pieter Dirksen and his honest family I remained a housekeeper for nearly two years, acquiring practical knowledge in all branches of farm management, and buying cattle whenever I had the opportunity. My own farm remained uncultivated, but I was just about to go and inspect my clumsy buildings for the kind of locks a Transvaal cattleman needs, when, returning one day from a buffalo drive, I met Karel Dirksen, my master’s eldest son, who informed me that a Tsulu man and his wife had arrived at the new farm during my absence, and that they had anxiously inquired when I might return. This was no unusual occurrence, for I was well known by reputation to most of the tribe, who often came to tempt me to mediate in their petty quarrels with their European neighbours, and so I rode home without further thought: but my astonishment was immense when my old companion Ula, looking sad, haggard, and miserably emaciated, came up to me at the door of a small outhouse, and without a word led me by the hand into the only shelter that could be found. There, on a rough plank bed, covered with flour dust, lay my foster mother, Landela, in a miserable state of exhaustion, suffering, to top it all, from a frightful wound, which had evidently been inflicted on her leg with an assegai or some similar sharp instrument. She was too weak to speak, but after explaining to Vrou (the housewife) my relationship with the unfortunate foresters, she hastened to bring them nourishing food, whereupon in a moment my old nurse recovered sufficiently to explain to me the reason for their appearance in this pitiful state, information which I might have obtained from Ula some time ago, had not her mother by signs forbidden her to speak. The frank telling of her sufferings afforded the poor wife more consolation at the moment than anything else.

It now became evident that Ula had attained a higher honour in the sight of the Tsululais chief than any of his companions: and as a mark of special favour, Cetewayo had intimated that he intended to raise the young warrior to the rank of a man at the next great feast, and at the same time to give him back the cattle and other property which had been confiscated by his father’s wrongful conviction. But this deliberate restitution greatly annoyed some of the king’s most powerful advisers, who, because they had received a share of their slain father’s estate, felt not the least inclination to throw their ill-gotten goods at his living representative.

To a Kaffir his cattle are of great value; he loves his herds as the apple of his eye, and would sooner sometimes part with his favourite wife than with some mad bull. This being the case, and the standard of justice in the Great Kraal being exceedingly low, it was not surprising that those threatened chiefs should unite and try to prevent the king’s politically absurd, though just, intention. Nor was it at all difficult to sow suspicion in the heart of the capricious forest prince; the same means which had so emphatically worked the ruin of that slain chief were still available when it was desired to accuse his son, and by the advice of the chief soothsayer or witch-priest of Cetewayo it was suggested to the king that Ula and his mother were plotting with the white men to overthrow him; and, moreover, that both were practicing witchcraft. In proof of this last-mentioned accusation, it was alleged that Ula and her mother had been seen aiming at the king’s apartment with some strange and powerful weapon.

The ruler ordered them to be on the lookout, and finding that this part of the accusation was largely true, he arrested and produced before him my unfortunate friends, together with the wicked mutiny with which they practiced their wicked magic tricks. This was no more dangerous than the scrap of a kaleidoscope[4] which, on my first return to the colony, I had presented to my fellow-creature. Knowing well the greedy nature of Cetewayo, he had been wont to conceal the possession of the treasure from his companions; but in the evenings, when the day’s work was done, both mother and son would sit down on the ground near the door of their dwelling, and amuse themselves until dark by turning the tube and admiring the many-coloured pictures which each new exercise produced. Unfortunately, the entrance to their little home opened directly onto the king’s residence, and thus the mutiny seemed to be a constant threat to the royal government mansion.

In vain did poor Ula attempt to explain the innocent nature of his delivery; Cetewayo saw that he had concealed the plaything, and this fact alone greatly angered him, and made him too susceptible to the vicious insults which Nkungulu and the others concerned were driving into his ears. He, too, no doubt, was fond of the kaleidoscope; and dreaded the thought of it once more falling into the care of its rightful owner; but, be that as it may, he declared that the charge had been proved, and sentenced both Landela and his son to death, the latter to be impaled, the former to be roasted on a red-hot coal, as is the custom among this people.

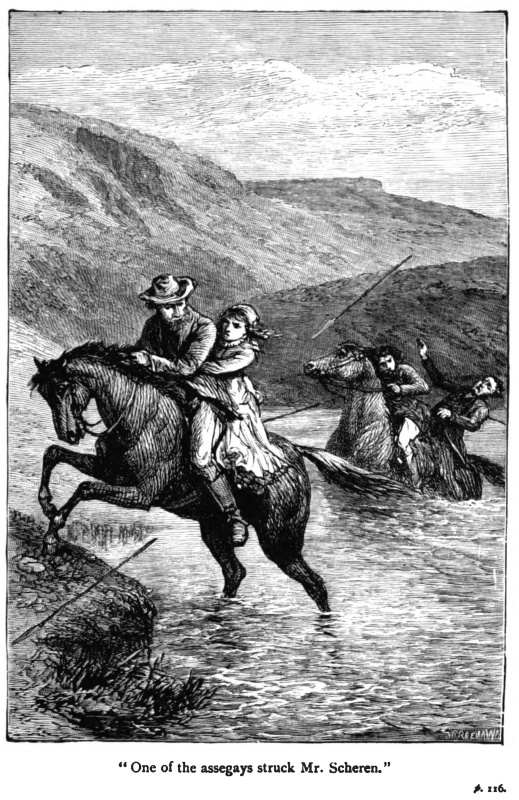

The execution was fixed for the next morning, but conscience must have troubled the king’s stony heart a little, for during the night a word from the king’s quarters called the guards away for a moment, and the prisoners did not fail to take advantage of the advantageous position thus given them. Just as they were about to pass the last dwelling, the owner of this, thinking the fugitives to be cattle thieves, threw them at my nurse with an assegai, which struck her in the leg. But Ula, lithe and swift as the antelope from which she had borrowed her name, seized the mother in her arms and carried her to safety from the nearest danger. It is easy to imagine the frightful hardships they had to endure, unarmed and without food as they were in the wilds of Africa, in the company of all kinds of wild beasts and snakes; for though they often passed within sight of their countrymen’s kraals, they were obliged to avoid intercourse with their nearest relatives, who would have taken them as fugitives, and sent them back to their deaths, from which they had so laboriously and with difficulty obtained them. At last the poor fugitives reached Pieter Dirksen’s news-house, where, as we have seen, they were given food and shelter, after having informed the Dutchman of my relation to them. This incident had occurred about a month before the day on which the story begins, by which time Landela’s wound had healed, and Ula had fully recovered from the hard exertions of the journey; and as he now stood before me on the edge of the pond in this sweet African morning, I could not help thinking what a noble expression of his people my friend was, nor without reflecting how blinded by prejudice those people are who admit no help to be found in the breasts of their black brothers.

We had finished our swim, and Ula gazed in eternal delight at the reflection of her shining body in the water, while I comfortably put on my clothes, which, although they consisted of few articles, were nevertheless more complete than those of my Tsululainen companion. Suddenly a cry drew my attention to the latter, and I saw him bending over the edge of the pond, and intently examining some object in the rapidly brightening dawn.

“One, two, three,” he read aloud, pointing to clear paw prints in the soft mud. “Three panthers, Kuta, have been here drinking last night.”

“Well then we have to get the drive going,” I replied, very worried about the cattle. “I hope they haven’t done any damage yet.”

“They must have been starving, otherwise they would never have dared to come so close to human habitation,” said my companion, who had still been examining the tracks. “That’s right, there are three of them, and one is quite a mess; look at this paw print, it’s more of a lion’s than a panther’s.”

At the same time, a shot from the direction of the house reached our ears, and as we ran in that direction we met Henrikki Dirksen, Boer’s youngest son, who, seeing us, exclaimed:

“Three of your brute beasts have been killed, William, and two of ours, besides several badly torn. That rascal Papalatsa, who was supposed to be guarded, must have gone to sleep last night and then run away to avoid the whip,” and the young Dutch giant shook his jambok (bullwhip) menacingly in the direction of the cattle yard.

This was bad news; for if we did not kill the robbers, they would probably renew their attack this day after dark. So the three of us went to the apartment to inform old Pieter of the accident. The Boer had just emerged from his bedroom when we entered, and his son, after saying a respectful good morning, told what had happened, at which the old man’s brow gradually grew more and more gloomy. Pieter Dirksen was of the finest type to be found in the stout Dutch breed of settlers that grew up in the Transvaal. His giant frame—he was three cubits and four inches tall in boots—had not been bent by the work and exertion of sixty summers; and the strongest of his sturdy sons would have been terrified to compare their strength with that of their muscular father. His face was wrinkled and his features were a few white, but that only gave a benevolent touch to his form, which in his youth had earned the name of sallowness; for Dirksen’s life had been spent in the wilds of South Africa, his learning had been limited to the little arithmetic required by his office, and to a reading capacity so great that he might read through a chapter of the Bible on Sundays, and so the intellectual intelligence which had been in him at first had been put to sleep. Calm determination and unbending will were the leading features of his face, though the benevolent hand of time had sown in them a gentle benevolence which made his form very agreeable. And yet, old Pieter had many faults common to the whole class of men to whom he belonged. No ox could have been more one-sided than he; and when the old man had once made up his mind, neither words nor threats could make him abandon the intention he had once decided in his mind. He was cunning in business matters, but at the same time hospitable; but he rarely showed himself in his most polite form if his guest happened to be an Englishman, for he regarded our people with all the prejudice of his kindred. And he could not sometimes refrain from venting his bitterness on me, although, knowing full well that his complaints were often too much to bear, I was not at all moved by those words, and I am sure that the old man regarded me more as a father than as a master. His opinions on the mutual relations between the white and black population were also completely at odds with our English ideas. He, for he believed that the natives should be the subjects of the Europeans, and rejected as both absurd and harmful all our beautiful ideas of equality. Nevertheless, he treated his Negro indentured servants with kindness and moderation, although on the other hand he mercilessly tanned their hippopotamus skins for every neglect. And I confess,I wouldn’t have liked to be the owner of Papalatsa’s back skin when Henrikki had ended his story by announcing the consequences of that boy’s carelessness.

An Englishman, on hearing that one of his animals had been killed, would probably have ordered his men to mount their horses and rode off at once to find the culprits; but old Pieter Dirksen did not. He had never undertaken anything in his life without thinking it over thoroughly, and he probably had no intention of rushing into any hasty action in this matter either. He listened with furrowed brows until his son had said what he had to say, and then, after considering the matter for a minute, he stepped to the door of his bedroom and said calmly to his wife: “Mary, bring us the fat without any fuss.”

Seeing clearly that the chase was coming, I went to my room to get some cartridges for my gun. But the strange incidents of this morning had not yet passed, for suddenly my old nurse burst in, shouting: “A messenger has arrived from the king. You will not leave us in their clutches, will you, Kuta?”

“That’s Kotsi,” remarked Ula, after glancing at the newcomer; “our bitterest enemy.”

“Then evil is coming. But don’t worry, Landela, the Dutchman won’t abandon you. Just stay here, both of you, until I return.” And with a heavy heart I went to meet the warrior, who, fully armed, was walking to the Boer’s room.

Chapter 2.

The king’s envoy.

The last observation which Ula had made increased the anxiety which I felt for the safety of my friend. Kotsi was well known to me, both in man and reputation, and I was assured that no trifling matter had occasioned his appearance as the king’s envoy in place of Pieter Dirksen. This warrior was one of Cetewayo’s most trusted companions, being the chief of the Induna-e-nkholu , or regiment of men, called the Onoba Ponkuei (panther-catchers); a name derived from the fact that these, by the command of their tyrannical master, had captured a panther alive and brought it before the monarch. Kotsi was but a young boy when this abduction was made, but he had already distinguished himself by the fearlessness with which he pursued the ferocious beast, and subsequent evidences of stout courage raised him to his present high position. Like most savage despots, the Tsululais king was troubled by the thought that a secret plot was being hatched to overthrow his power, and, fearing that his oppressed subjects would one day kill him, he had surrounded himself with a guard of chosen men, who, on the grounds that by his death they would lose everything without gaining anything, would protect him from danger for their own good. Kotsi was the head of this group, and I knew that only some important event could induce the king to let his favorite go from his vicinity.

In the meantime the warrior had reached the open door of the apartment, and after knocking several times with his knob-knife ,[5] stood calmly awaiting an answer to his knock. He must have sensed my approach, though he did not seem to be aware of my presence, a fact which in itself boded ill for my friends. Mentioning him by name, I bid him welcome to the news-apartment; but he took no notice of my greeting, but, fixing his gloomy gaze on the back of the room, settled down completely indifferent to me, with a calm, lofty haughtiness that put hot blood to a severe test. Fortunately old Pieter entered before I could empty my gall into the messenger, and the latter turned to him, with a proud nod of his head. Although Boeri had a helpful knowledge of the Tsulu language, the speech was largely incomprehensible to both him and his sons, who had also come into the room, for the warrior uttered his sentences with infinite rapidity, gradually pushing himself into a real frenzy of enthusiasm as he spoke. He paid no attention to anyone but old Dirksen, though he knew very well that I was listening to his rhyme; but when he had finished he half-nodded at me, evidently saying: “That is what I have to say; now make it known to your friends.”

I was terribly disturbed by the boundless insolence which the king’s favourite displayed in every one of his communications—a conduct so vastly different from that in which the natives usually treated Europeans. He was evidently acting under orders, for without the permission and knowledge of his master no Tsulu would have dared to enter a white man’s room and utter such threats in his presence. If I were to cut out from the envoy’s sentences all the flowery imagery with which he adorned his speech, it would almost read as follows, though it is impossible to express with pen and ink the practiced insolence with which every threat was seasoned.

“Old white man. I am Kotsi, chief of the panther hunters, whose duty and pleasure it is to guard the sacred majesty of the great Cetewayo, chief of chiefs, the Black of the Black, lord of countless herds, the Ruler of nations, the Slayer of tribes. From him I come to you, the white old man, to speak in his name: White old man, snow-haired, you have settled on my land without permission, taking possession of a wide strip of my territory and grazing your cattle and herds there. This I can forgive, for I love white men and want to live in peace with them and their kind. But you have done more. Not content with usurping foreign territory, you have taken as your protection criminals who have been condemned to death by the laws of their country; you have given a vulnerable refuge to evildoers who have plotted against the life of me, their king. I cannot believe that you are This you have done out of ignorance, for there is a man under your roof who is too well acquainted with the conduct of those criminals, who, moreover, gave them the weapon with which they laid wait for my life. But, nevertheless, my heart is tender towards the white men, and I would rather believe that you have been deceived than that your strange conduct is a whim. Therefore, in all good will and friendship, I send to you Kotsi, the chief of my guard, to make you know that you, nor your family, nor your cattle, nor your servants, have anything to fear from my subjects. Moreover, I give you permission to take possession of the territory at the foot of Mount Eloya, which the Englishman William Thornton intends to usurp; for his plot against my life will annul all agreements between us. All this I will do, but on one condition. You must leave both “The evildoers who now reside under your roof, into the hands of Kotsi, and send to me at Thornton that Englishman, all the cattle. Each of the criminals shall meet the death to which they were condemned, and the decision shall show the third that I am not the man who can be threatened with impunity. Consider this condition, and communicate your decision to my faithful servant Kotsi. If you do as I wish, your house will be safe, and you will have a friend; but if you reject my offer, I will send my warriors to seize the criminals and destroy your house; and then, if resistance is attempted, your blood will be on your own heads.”

Such was the content of the speech which Kotsi delivered in our presence, and doubtless, having reached this point, he should, according to the most missionary rules, have waited for Boer’s answer; but, carried away by the whirlwind of his own eloquence and filled with the bitterest hatred against Landela and his son, he added, for his part, a little advice to old Pieter.

“Yes, white man, and my king will do it. I, Kotsi, the panther-bearer, tell you that he will do it. Cetewayo is an elephant; he will crush you under his feet if you do not obey. He is a lion, and he will tear you limb from limb if you resist his law; he will devour you as a hyena crushes the bones of a slaughtered calf. Obey him, you white-headed old man, or tremble for yourself and your children.”

During this speech the settler’s wife and daughters had crept quietly in, and no doubt their presence induced the messenger to adopt a more threatening tone, in the hope that the timidity of the women might influence old Pieter’s decision. And the chief of the panther-soldiers was by no means a pleasant object, as, having concluded his speech, he stood staring about him, and the eagle feathers that adorned his shaved head trembled with excitement, and the leopard skin that formed a sort of kilt around his waist was caught in a fluttering movement. He was a wild-looking forester, but at the same time frightening, and little Liisu, a curly-haired girl of thirteen, rushed out of the door in fright, when Kotsi, to conclude, slammed the table with a harsh force with his knob-kirri.

But the hard-hearted old Boer and his son would not have been so suddenly frightened, even if a whole legion of such cruel warriors had been coming against them; at least, when the chief struck the table, Karel Dirksen showed such a marked tendency to throw the guest through the open door into the yard, that I had to put my hand on his shoulder to restrain the young, impetuous giant, a swift act that the inhabitants of the country would never have forgotten. To prevent violence, I immediately translated the envoy’s sentences to the old newcomer, who listened to them from beginning to end, without the slightest expression on his face indicating what was going on in his mind.

After a few minutes’ thought, my master replied: “Tell Tsulu that it is never my custom to rush about in thought. Tell him to come back in the evening, when we return from the day’s work, and then I will give him my answer. And since we are going to kill those wild cats, tell him that he and his husband may come with us if they please. Now, Maaria, give me the money; and then, boys, let’s go.”

Kotsi had, while old Pieter was speaking, fixed his sharp eyes unblinkingly on his face, and disappointed hope darkened his dark features as he saw the unperturbed calm with which the newcomer listened to Cetewayo’s message. “Have you told him the truth?” he asked suddenly, turning to me. “Have you told him that his kraal will be destroyed and he and his family will be killed?”

“I have interpreted your words as best I can,” I replied, “and you have received your answer. Do you agree to join me in the hunt?”

“Will Ula be present?” asked the messenger, burning with an inner impatience to show the white men his bravery, but still uncertain whether propriety would permit him to join in the amusement in which the man whose death he was attempting would be involved.

“Ula is about to arrive,” said my brother-in-law, who at that moment entered the room fully armed, shield and assegai in hand. “Ula is about to arrive, and then let the leader of the Panthers, who is waging war against weak batteries, show whether his father’s size [6] or Ula, that ‘boy-stupid’, will be in front, harassing the beast.”

Both men stood, snarling at each other with all the fury of savage enemies, and blows would very soon have followed this rapid call to battle, had not Karel Dirksen thrust himself between them and thus effectively prevented them from striking each other except through him.

“No violence under this roof,” I shouted to the Tsululainen. “Can’t you stay away from each other’s throats for the evening? So put your anger aside until then, and walk side by side like countrymen and not enemies. You, Ula, promise not to harm the chief, and he, on the other hand, will not take advantage of the opportunity against you. Be partners for a few hours, without growling at each other like angry lovers.”

The Tsulu nature is not like anything except what we would call brutal chivalry, and when I further pointed out the great advantage we would have from the assistance of so good a hunter as Kotsi was, this black warrior softened a little, and so at last a truce was arranged between the two men, which was to last until the return from the great hunt. And it was very illuminating as to the nature of the Tsulu to observe how freely the enemies conversed, for when the ice between them was once broken, all bitter feelings seemed to have been left behind, and in their place there had been a fine dispute as to which of them would show the most courage in the dangerous undertaking on which we were about to embark. Kotsi and Ula went together to the hut where the latter lived, and there Landela now prepared a hearty meal for the guest, whose arrival had at first been as unpleasant as it had been unexpected.

After Vrou had placed a large platter of game on the table, and coffee to wash down their throats, the whole family set to work as carelessly as if Cetewayo and his herd had been north of the equator! The thousand ups and downs of the life of a settler, together with the slowness which is inseparably connected with the Boer character, made this respectable family more grieved at the ravages of the four-legged bandits who threatened their cattle than they were troubled by the news that the Tsululais chief intended to seek them out in his vengeance unless certain impossible conditions were agreed to. And no one who saw old Pieter sitting peacefully enjoying his game roast could have guessed from his appearance that the last word had just come into his fingers from the mighty and vengeful bushman. And yet the message did not disturb his peace of mind in the least, for all his thoughts were now fixed on his cattle, and those two cattle killed by the leopard grieved him much more than Kotsi with all his threats.

When the suurus was eaten, we mounted our horses, which had been brought before the door. The faces of the negro servants evidently showed great curiosity as to the matter which had occasioned Kotsi’s sudden appearance at the new residence; but this personage was too high in their nation to be able to inquire at all, and statesmanship or other considerations prevented him from publishing the secret of his mission. Half a dozen armed warriors, who had followed him, but who had hitherto carefully kept out of sight, now came forward, and in a few minutes the party was on their way. The Boer and his son were armed with heavy single-barreled roers (fire-slingers), which are in general use among the Dutch settlers. The Tsulu each carried his shield, and his assegai; and I had only a double-barreled breech-loading gun. Several of the servants of the new house were leading fierce forest dogs on leashes, and a pack of domestic dogs of all sizes and colors barked and snarled around our horses, disobeying the heavy blows that the black-skinned assegais were delivering to their cadaverous ribs.

It may be well to mention at this point, to those who are not familiar with the subject, that the Tsulu warrior, whether on hunting expeditions or on his even more dangerous warpaths, carries with him two kinds of weapons for assault, and a third for rebellion, which he uses only in defense. These are: the assegai, the knob-kirri, and the shield.

The first is a broad-bladed iron axe, usually of the work of the natives, with a shaft about five feet long, with the thicker end of the handle nearest the stock. Each warrior carries several of these weapons, and usually hurls them at the enemy from a distance of about forty cubits. Chaka, the famous Tsululai tyrant, forbade the use of the assegai as a throwing weapon, thus forcing his people to engage in close combat with their enemies, and to use the weapon as a bayonet or a dagger. But his successors reverted to the former practice, and the assegai is now used in both ways — that is, the warrior folds the shaft when engaged in hand-to-hand combat; and uses the shortened weapon as a spear.

A knob-kirri is simply a club made of hard and heavy wood, and most often a warrior, when going into battle, leaves it at home, whereas he usually takes it with him on hunting expeditions.

The shield speaks for itself and needs no explanation. It is made of oxhide, about a foot and a half long, eighteen inches wide, generally oval in shape, and is carried by a handle attached below the center. The color of this weapon indicates the regiment and rank of the owner. It would be useless to attempt in these pages to give an account of all the strange distinctions of rank among the Cetewayo; I have reached my purpose by observing that all the men —that is, the warriors with their father’s size and shaved heads—bear white wings, while the black shields belong to boys or young men, some of whom may already be forty years old.

Many of the most prominent chiefs and warriors have gunpowder guns, but the assegai is their national weapon.

Our road passed a kraal, or large circular enclosure, into which the cattle are confined at night. All the animals were now scattered about on the grass, in herds of ten or twenty. The steady cows and bulls were eating in peace, and the more cheerful calves were amused by leaping and galloping in merry circles, their tails erect. It was a sight to gladden the heart of a native emigrant, and no feeling of uneasy dependence could be discerned on Pieter Dirksen’s face as he looked at the gaping cattle that called him their master. But suddenly there was a strange movement in our servants, who, fearing that some wild creature might escape our notice, were peering into every bush and thorn for a hundred yards round our road. A series of exclamations in the Tsulu language, and a shriek from the mouths of some black women, who, with a child girt about their loins, had followed us so far, caused us to spur our horses and to turn to the spot, when, to our astonishment and horror, we found the mangled body of Papalatsa, the missing shepherd, the man whose absence we had supposed to be due to fear of a flogging. There could be no mistake as to the manner in which the poor boy had been killed. His wife, now his widow, whose scream we had heard, was on her knees, holding in her arms the lifeless head, the back of which had been crushed like an eggshell by the scraping of the powerful paw of the panther. The face was calm and uncontorted, and except for a red streak that flowed from each nostril, there was not the slightest sign of pain or suffering in the form. But the underside of the body was horribly torn and covered with the marks of both teeth and claws; it was evident that wild beasts had feasted on the poor shepherd’s body.

“How could this have happened?” asked old Pieter; “the boy would never have wandered within half a mile[7] of the kraal on his own.”

Ula and Kotsi, who had been examining the ground, now showed us that a leopard or lion had dragged the body to its present position. There was a mark made by the other dragging hand of the victim, and the shreds of his light loincloth were visible in the thorny brambles that had fallen into the path of the retreating beasts.

“The matter is clear enough,” said Kotsi, turning to me; “a leopard with two cubs has killed a boy. It has jumped over the kraal fence and killed the cattle, but found its strength too small to carry the carcass to its cubs, who were not yet able to climb over the fence. Papalatsa must have tried to drive it away when it was killed, and seeing him weaker than an ox, the beast dragged him to this place where the cubs could eat their treats without being disturbed, is that not the case, Ula?”

My plant brother nodded in return, and further examination revealed the tracks of several panthers, proving the warrior’s suspicion correct.

“It is time for us to hurry,” cried old Pieter. “The beasts have fled to the gorge of Mount Slangopies, where we will find them sleeping, digesting their food. Let the other women help the poor boy’s wife in a suitable way to lower the body into the grave.”

We rode on, but looking back from the saddle, I saw the widow sitting motionless in her former position, holding her crushed head on her knees, and sadly peering at the lines of her face that had become fixed for ever. No cry escaped the lips of the lonely mourner, for it seemed impossible for him to comprehend the full extent of the misfortune that had befallen him. It seemed heartless to leave his grief-stricken wife alone, without attempting to console her; but the safety of the cattle depended on our success in destroying the savage robbers who had found their way into the cattle kraal; and before we had got within a yard of the body, the blacks were laughing and jesting, leaping over the grass with such speed that our horses could hardly keep up. The approach of death does not much move these people; and a corpse is viewed with eyes of horror rather than pity.

Along a steep, wooded pass a small river rushed down from the ridge of the mountain and disappeared into the valley below. Here the blacks thought the beasts had chosen their refuge, and when we reached the mouth of the lowland, old Pieter stopped to consult how best to drive them from their hiding place into the open. After a short discussion it was decided that a pack of Tsulu, led by Ula, should go round the pass from behind and, forming a line, advance towards us, searching every inch of the ground and driving the creatures, every hoof, towards us. We Europeans were to form a semicircle and prepare ourselves with warm hands to receive the panther.

After two hours of tedious waiting, the sounds of the riders began to be heard, and having dismounted from our horses, we prepared to fire. Suddenly, a tremendous shriek from the advancing blacks announced that the creature had been seen, and Kotsi, who stood trembling with excitement at my side, seized my arm, indicating the yellowish object that was slithering from one bush to another.

“There’s the panther,” he whispered. “Furious as they are, the dogs have been released from their chains.”

It was all too true. The handlers of the dogs, on perceiving the beast, had let go of their leashes, and the whole pack rushed wildly towards the creature, which, seeing them approaching, retreated into the dense grass, which perfectly concealed its movements. The dogs attacked it without hesitation, howling with the desire to catch its prey. But soon there were shrill cries, mingled with sudden growls; and soon after, first one, then the other, crawled lamely away from the unequal struggle, while the gallant barking of the unharmed companions was changed into a wild roar, over which was heard the strong whining of their quarrelsome brother. All our efforts to call away the wild-headed dogs were now in vain, and it was impossible for us to shoot into the reeds, for then our bullets might have injured the animals we wished to protect.

“Oh my god, nothing will come of this,” cried old Pieter, when a loud bark announced that yet another dog had received its fatal blow. “We must stop this slaughter”; and with his trap in full swing, the Boer now approached the scene of battle.

But before he had gone ten paces towards the island of Kahilasaari, a ghost darted past him and disappeared into the waving reeds; it was Kotsi, the panther hunter, who now saw an opportunity to show his ferocity and skill. At the same moment Ula appeared at full speed and scuttled, breaking into a jumble of Dutch and Tsulu: “Don’t go, baas (sir); go back, Kotsi, go back; it’s not a panther; it’s a lion. You’re lost.”

But the chief of the king’s bodyguard either did not hear or did not care, and only the waving of the reeds showed that he was still moving forward. Suddenly there was a roar, loud and terrifying, which drove the most common black-skinned people like sheep to the nearest shelter, and at the same moment a handsome lion sprang forward, assegai at his side. He paused for a moment to look at his pursuers, during which time he was the laughing stock of a dozen spears and bullets; but these seemed rather to increase his fury, for, roaring a second time, he charged at old Pieter, who stood calmly waiting with his gun to his cheek. I hastily discharged my second barrel at the wild beast, but could not check its progress, and in the twinkling of an eye I saw that the Boer’s weapon had failed. In the next second my good old master lay a mangled corpse: human aid seemed powerless to avert his destruction.

To escape the sight of the horror which I could not prevent, I turned half away, and was in a hurry to put fresh cartridges into my gun; but a sudden cry made me look again at the wretched scene, when, to my great astonishment, I saw the old Boer still standing, and shaking fresh gunpowder into his old sluice, as coolly as if, instead of a lion, an ordinary house-cat had been a few yards away from him. The beast stood with his fore-paw on some dark object, roaring wildly, and lashing the ground with his tail; but now old Pieter’s fire-tube rumbled, rumbled like a cannon, and the lion fell to the ground, his skull pierced.

With a vague fear in my mind as to who would be the victim, I rushed to help the unsurprised Boer, who was pulling my plant brother from under the fallen beast.

“He saved my life,” said the newsboy; “he charged forward to confront the lion, and plunged his assegai into its breast. Poor boy! I fear he is a dead man.”

I had bent over Ula’s unconscious body and raised my hand to her heart.

“It’s still beating; he’s alive,” I shouted. “Give me the bottle, Henrik; maybe we can save him.”

Nor was he dead; strange to say, quite unharmed, except for a severe blow on the right shoulder, and a terrible concussion. Whether his unexpected charge upon the animal had so stupefied and confused it, I know not, but the blow of the deadly paw had struck with all its force upon my friend’s broad shield, and thrown him to the ground with such speed that he was almost unconscious; but this saved him from the claws, and partly averted the severity of the blow.

In the meantime the young Dutchman, with the blacks, had entered the island of Kahilasaari to kill both the cubs they found there, and to bring away the unconscious body of the panther-catcher, whom they found beaten to death. He was still breathing, and a drop of brandy refreshed him so much that he could recognize us; but he never said another word, for the lower half of his face was torn off, and in a few minutes the man was gone.

“Tell his people,” said old Pieter to me, referring to the Tsululais warriors who stood in a group around their dead chief—”tell the members of the king’s bodyguard that it was my intention to give their leader an answer tonight on one of the two conditions that Cetewayo had set before me. Now I resolve, in the presence of this dead warrior, that I will never expose them to Ula’a any more than I would their mother. They came to me for shelter, and that they will get. I would not abandon them in any case, but now the boy,” and he laid his strong hand on the shoulder of my plant brother, “has saved my life, and I will show him that a Dutchman does not forget a good deed. Let us go home, boys, to dinner; I am hungry.”

3rd Chapter.

The autocrat in his council.

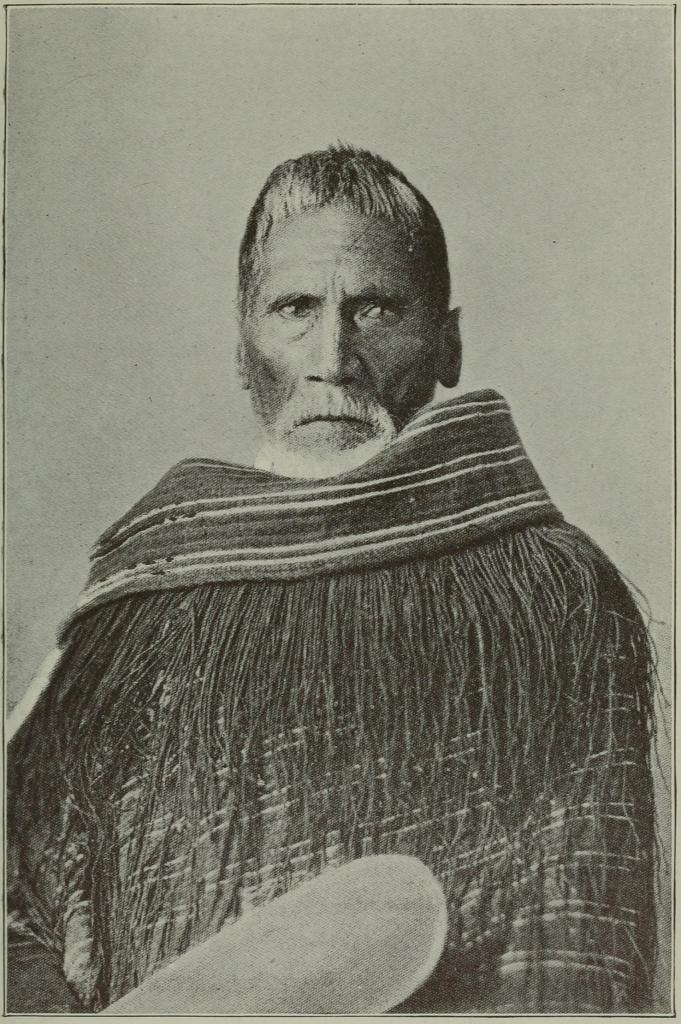

Cetewayo, King of the Tsulu, was in his harem (concubine house), in the great kraal at Umpongen. Around him was everything that one would have thought the heart of a sovereign could embrace. Here were wives and concubines of the grain, ready to stroke the royal forehead if too many tilts of the olive-harvest should bring the cooper to his temples; there were three regiments of warriors, whose purpose was to leap before his majesty, or if bloodshed was more to their master’s taste, those gentlemen were ready to besiege and slaughter the inhabitants of the neighboring kraal, or to commit any other cruelty that the capricious mood of the tyrant might command him. One would have thought that Cetewayo would have been the son of fortune in such relations. But such was not the case. Deep discontent clouded the royal countenance, and the position of such wretched animals, whom duty called into the proximity of the monarch, was anything but enviable.

Of late things had gone against the wishes of the great king. It was easy for his Imbongo [8] to hail him as “the elephant’s calf,” “the cow’s son,” and “the promoter of men”; but, even if such titles were granted as appropriate, they made no impression on the Portuguese merchant at Delagoa Bay, who, having produced for him a large consignment of breech-loading guns at a cheap price, now refused to procure ammunition except on the most extravagant terms; and without cartridges, the guns were, of course, useless. Being “the elephant’s calf” did not bring the king cattle to satisfy the merchant’s demands, and it seemed more than probable that he would eventually be forced to part with some of his favorite beasts. Besides, the men who had followed Kots had returned to the king’s kraal the night before, and had made known the death of his favorite, and the prohibition of old Pieter Dirksen to leave Landela or her son in his hands. All these facts greatly angered the monarch, and his shield-bearer, whose duty it was to hold the great shield between his master and the sun—an office which gave him a splendid opportunity of studying the king’s features—saw plainly enough that a storm was breaking out, and only fervently hoped that it would fall on some other head than his own.

In addition to this, a third circumstance had arisen to disturb the autocrat’s peace of mind, a small, everyday incident that would hardly be worth mentioning if it had not turned the king’s thoughts in a certain direction and led to decisions that were of great importance to me and my friends.

The reader may remember that I had presented my fellow plant with a kaleidoscope. This instrument, of course, after the judgment of Ula, fell into the hands of Cetewayo, and was used for a time to amuse the sovereign in his idle moments, but was finally thrown into the custody of his favorite wife, his youngest spouse. The dark beauty, having turned the tube around with the deepest wonder, was seized with a burning curiosity to see several of these variegated objects at once, and, supposing that the interior had been filled with innumerable pictures, she tried to pull them out, with the result that the toy instrument broke. With great cunning the young lady had laid the blame on one of her quite innocent maids, who, by the king’s order, was cruelly whipped; but besides the fact that the injury to the rebel was a source of annoyance to the king, it also caused him to send the instrument to the German Mission with the request that the pastor would immediately put it in perfect order. This Arnold Beidermann did without much difficulty; but in bringing the unfortunate toy back, he considered the opportunity to interfere in the matter on behalf of the girl who had been punished for the queen’s crime, and therefore reproached the autocrat’s injustice in the harshest terms, for the victim was one of the former pupils of the mission school. This incident had occurred the day before, and the king’s memory was still bitter with the reproach, which he had been able to accept in the hearing of all his advisers. So, as I have said before, Cetewayo had much to be angry about, and though he sniffed whole handfuls, spooning the stuff into his nostrils, and drawing in such large quantities that tears of grain dripped down his swollen cheeks, neither the tobacco nor the harsh sips of the barleycorn he swallowed could calm his stormy mind, and his shield-bearer saw with an inward shudder that sooner or later the violent atmosphere must burst.

Now Imbongo arrived with word that the troops were in battle array, awaiting the review of war, and immediately the king set off, accompanied by a boy who carried his snuff-box, and at his heels a shield-bearer, who with the greatest care held his shield so that not a single ray of sunlight could fall on his noble lord.

Cetewayo was preceded by the “Praiser,” an official whose duties might seem somewhat comical to Europeans. At first he ran across the plain, waving his arms like windmills, and stretching his neck like a camel crane; then he threw himself down on all fours, and bellowed with a voice that would have made a bull split with envy, contorting his body into various shapes, which he thought represented the movements of a lion; finally, that incomparable clerk raised one arm high in the air, arched his back, and gave a snort, by which he attempted to represent an elephant; and as this madcap antics took place in the scorching heat of the sun, the sweat fell in heavy cranberries from the poor half-madman, whose office was certainly no job for the lazy, as it required both great flexibility and lungs of brass; for after every description, Imbongo glorified the titles of king, exalting him above all the rulers of the world, and so devoted himself with all his soul to the task, that when Cetewayo had finally seated himself on a sort of portable throne, opposite his warriors, the “Praiser” lay prostrate in the dust of the earth, in a state of real or feigned insensibility.

The regiments now marched before him, each warrior, as his master passed, lowering his shield and bowing his forehead to the ground. Now and then one of the chiefs pointed out some distinguished warrior, after which a halt took place, and the person in favor charged out of the ranks, to display his agility by several leaps and bounds, wonderful to behold. A certain poor old man, whose sinews had been somewhat stiffened by the grips of time, could not perform this fool’s game to the ruler’s satisfaction, and was immediately, by the latter’s command, mercilessly whipped with knob-whips.

When the troops had passed by, the king ordered that an ox should be slaughtered for each regiment, after which the warriors, after showing their gratitude with long-drawn-out shouts, stabbed the condemned savages to death with their assegais, and now the review of the troops was over.

Having refreshed himself with deep sips of olive oil, Cetewayo called his council together, and without preamble set forth the various causes which disturbed his peace of mind. To this the Tsululais senate listened with the greatest attention, but without proposing any means by which the difficulties might be removed. At length, when it began to appear clearly from the king’s countenance that the silence must be broken, Nkungulu, the chief soothsayer, spoke thus:

“The King has an enemy,” he began, roaring around the circle, every member of which felt himself sinking to the ground at the sight of the traitor, for the accusation of this kind meant plundering of property, if not death. “The King has an enemy: let us see who the evildoer is. The Delagoa merchant will not give the Tsului ammunition, and without it our people cannot swallow the British, who have invaded the King’s country and are protecting the King’s enemies. Now the thing is, that Portuguese would never have dared to do such a thing, unless his mind had been poisoned against the King. And who could have done it? Nkungulu knows it; he is a priest and can smell the evildoer.”

The counselors looked at each other with horror, for it was certain that one of their number would be mentioned; but the seer had no intention of accusing any of his own people. He looked at the missionaries, to whom the late king Panda had given permission to settle in the country, with bitter hatred, for they had on more than one occasion attempted to expose the foolish tricks on which he relied in practicing his frauds, and Arnold Beidermann had not deigned to declare him a villainous traitor, seeking his own advantage at the expense of his fellow men. He had often used all his influence to incite Cetewayo, predicting famine and drought unless the foreigners were expelled, but the king felt himself unable without gunpowder to contend with the Europeans, and was too wise to undertake a course which would surely bring him into conflict with the British. A large consignment of guns had recently arrived at Tsului, however, and these necessary supplies of ammunition were only wanted, that the king might be quite unconcerned about the enmities of his powerful neighbours. And that Cetewayo intended to break the peace with his neighbours as soon as his army was sufficiently equipped, the witch-priest knew; he had been present the day before when the German missionary had denounced the king’s injustice in punishing an innocent person for the queen’s crime. Nkungulu saw that his master, unaccustomed as he was to the least opposition, was in just the right frame of mind to which a little cunning provocation would open his ears to every accusation that could be made against the white men; and with all the cunning of a senseless savage he now set about to carry out his designs.

“Nkungulu can smell the evildoer,” he continued, “but the evildoer is not here”;—a sigh of relief rose from the breasts of the assembled senators, which did not escape the notice of the cunning orator, who knew that fear would make the others pull together in every story he thought best to weave together—”no, he is not here, but yesterday his presence polluted the air and stung my nostrils.”

“Speak!” burst out Cetewayo; “name without fear who is the evildoer”; for that poor schemer stammered, as if he would not publish the name of a suspicious person.

“It is a white priest,” said the soothsayer, thus demanded, “a white priest who lives in Kagas and who rode out of the royal kraal yesterday.”

“Yes, yes, he is—he is,” echoed the assembled council, who rejoiced wholeheartedly that none of them or their people were appointed to die. “Listen to Nkungulu; he speaks the truth.”

The witch-priest had examined his master as he made the accusation, and, immediately perceiving from the king’s countenance that his speech was not objectionable, he proudly continued:

“It was the white priest who prevented the Portuguese merchant from bringing in ammunition, threatening to denounce him to the British. It is the white priest who has always shown himself to be an enemy of the king. Did he not refuse to give cattle to the warriors who were sent to search for those criminals, Landela and Ula, even laughing at the royal rank as a disgrace and openly expressing his hope that the criminals would escape? Did not that Englishman Kuta, or Thornton, visit his house for a month and there learn from him to rebel against the royal rank? Did he not travel here to meet the Portuguese merchant, although we tried to prevent him? Before that visit it had already been promised that ammunition should be procured; the white priest told the merchant that payment for it would never come, and so he refused to send it. Furthermore, did he not insult the king in the hearing of the council? And, finally, has he not shown that he is such a “Let the king and his people listen to the words of Nkungulu and drive out of the country the evil-doers who give him so much trouble, who protect evil-doers, and who everywhere snoop on his activities, drawing them on pieces of paper, so that people a thousand miles away may know what is going on in the sacred precincts of the Royal Kraal. Let the king, in his mercy, not condemn that witch to death, as she deserves, but send her out of the country without delay, and the herds of cattle which she has robbed of the Tsului will then increase the king’s funds for the payment of ammunition. When the spies are swept out of the country, then gunpowder and bullets will appear before long.”

“Well said,” cried the councilors in unison. “Let the white priest be driven out, and let the king send his army to devour that shameless Dutchman who will not leave the criminals in his hands.”

The Tsulu are the greatest orators in the world, if anyone would listen to them, and now every member of the assembly began to bring out some story detrimental to the missionaries, mixing truth and falsehood with such skill that an unprejudiced listener could not help but consider Cetewayo a lovable, good-natured ruler, to whose proper laws the white priests had shown the most impudent disobedience, inciting the people to rebellion against their lord and king, and bringing discord into the country instead of the peace of which they professed to be the messengers.

And I must mention here that Nkungulu’s accusation was largely based on facts. Arnold Beidermann had taken me under his roof when the wretched fever of this country had confined me to bed, had tenderly nursed me with his daughter, and had finally accompanied Ula and me in the search for land, which then ended in my selecting a strip for myself in the vicinity of Mount Eloya. It was indeed mainly to the local knowledge of the German that I succeeded in obtaining possession of so lovely a district of meadows, and perhaps the hope of becoming neighbours—in South Africa, you see, every resident within a hundred miles is entitled to this title—made him sacrifice more than his usual benevolence for my sake; for this was by no means the first occasion on which the missionary and I had had to deal with each other.

Looking back to my earliest childhood, the tall, thin ghost of Arnold Beidermann and his gentle blue eyes seemed to me old acquaintances, I began as far back in time as my memory can explain. I remember with what respect, when I was still a boy on the banks of the Tugela River, with Ula and the other Tsululais in my company, I looked upon Mrs. Beidermann, and what curiosity her little curly-haired daughter excited in me and in my companions. The kind-hearted lady would gladly have taken me, little wild-headed as I was, into her bosom, and been to me a substitute for the mother I had lost; but this the newsagent to whose care I had been entrusted would not consent; for he was a one-sided and unsympathetic, though well-meaning man, who, among his other whims, greatly despised the missionaries and their work. However, Mrs. Beidermann persuaded her enough that I was allowed to spend my days at the mission from time to time; and on one occasion, when some unexpected circumstance called mother away, I was allowed to take care of little Minna. It was then that an incident occurred that will never fade from my memory.

At this time I was nine years old and Minna Beidermann was two years younger than me. We had been strictly warned not to leave the corners of the mission, but when my little companion expressed a desire to pick some of the many-flowered bluebells that adorned the meadow, dancing in purple changes of color, I did not remember much of the warning, but followed her into the forbidden area. After all, I had spent hours with Ula in the same hayfields, much wider than the field on which the pastor’s house stood, and no harm had ever come to either of us; what danger could there be in picking a few flowers now?

Little Minna was delighted with the floral treasures that surrounded her everywhere, and threw herself gaily into the midst of each brilliant flock, mercilessly plucking flowers from the ground, which, after we had gone a few steps, were thrown away again to make way for others of a different kind. The multi-colored flowers were nothing new to me; I was accustomed to passing by them without paying attention, and it gave me great pleasure that my little companion could find amusement in such a trinket; if the floats had even been edible berries, then I too would have shared in the same feelings of pleasure with her.

So long we wandered, forgetting all but the happy present. I had thrown myself down at the foot of a bush, and was trying for a while, with the feeble assegai, which, young woodsman as I was, I always carried with me, to dig a large lizard out of its hiding-place in the ground, when a slight noise fell upon my ear, and as I sprang up I saw Mrs. Beidermann a few paces from me, her face a thousand hairs, and her hand stretched out towards the spot where her little daughter had just been playing. My eyes followed the direction indicated, and there I saw a sight that filled my soul with horror.

Sitting on the ground, little Minna still held a small book of red-flowered geraniums in her small hand, and her pretty head, from which her wide-brimmed hat had fallen to the ground, swayed slowly from side to side, as if the child had struck the time to some inaudible music. Her back was to us, so that we could not see her face, but our whole attention was fixed on the object, the evil proximity of which threatened the little girl with the most immediate death. In the windings peeped from behind a bush, which the equally lively child still held, a green inamba , the most feared of all South African snakes. The reptile had raised its head to the level of the girl’s face, and, with its eyes shining and its mane raised, swayed slowly and gracefully to and fro, two feet from its victim, who set the pace for the worm’s slitherings, evidently terrified by its awful proximity, and unable to utter a cry of distress, or make the slightest effort to escape the terrible monster; for it was the largest snake of its kind that I had ever seen.

Poor Mrs. Beidermann seemed as spellbound as her little daughter, and stood as still as a statue. The terrible horror that seemed helplessly coming had taken all her thoughtfulness from her. Once she looked imploringly at me, but her eyes soon turned back to the reptile, and she made no attempt to go to the child’s aid. The snake’s evil look had fascinated her too.

In my travels with the Tsululai boys I had often encountered inambos , which the natives regard with the greatest respect, and never dare to kill even the most venomous species; for it is a prevailing belief among them that the spirits of their ancestors inhabit the bodies of these reptiles. My acquaintance with the animal had therefore relieved me of the fear which had rooted the lady and her child to the ground; and, falling on my knees, I crawled in the direction from which I might approach the worm from behind. The bushes and bushes hid me from view as I crawled, and the reptile was evidently too busy with its unfortunate child to notice the slight rustle which my approach made. Carefully raising my head, I saw that I had reached my brainy position, and not a blink too soon, for little Minna’s head was indeed tilting closer and closer to that swaying monster that in another second would have wrapped her in its deadly coils.

Exerting all my resolve, I rose again, and, taking steady aim, plunged my assegai into the serpent’s body, just below the place where the neck rose up in one of the coiled coils. In a moment the wounded worm had coiled itself around the quivering shaft of the assegai, which I presently released from my hand; but my thrust had pinned the inambo to the ground; and the moment its gaze had been turned away, Mrs. Beidermann’s senses returned. Rushing to the spot, she snatched the little girl into her arms and fled the house, I at her heels; for I was too much in the throes of the blow to think of anything else but getting to the safety of my companions. Thus ended the adventure which at one time threatened destruction to Minna, and I have often since thought that, had I been a little older and better understood the danger of my undertaking, I would probably have chosen a more cautious method of escape, which would not have resulted in the same success as yours. The child himself had not the least idea of the fearful danger from which he had escaped. And naturally at that age he was unable to explain his feelings; but from what he said, they were by no means of a disagreeable nature. People who have not had any dealings with snakes assert that they have no power to entangle and charm a human being; but sturdy, strong-bodied men have sometimes been under their spell in the open meadows, and know how to draw the other way.

The little knowledge which I had before I left Natal for England had been instilled in me by Arnold Beidermann; and on my return to the colony eleven years later, I hastened to greet my old teacher, who had obtained permission from the King of the Tsululais to establish a mission in this country, at a place called Kagas, between the Pongola and Black Unwelosi rivers. I saw my little friend Minna grow up to be a large, beautiful girl of sixteen, the support and security of her father; for death had visited the missionary’s small family, and that good Laura Beidermann was now sleeping under a few willow bushes on the banks of the Tugela river. It was only after this incident that Arnold had moved inland, hoping perhaps by a change of place to assuage his longing for the faithful wife who had followed his destinies in storms as well as in daylight; for once Beidermann, with his natural gifts, might have soared higher than as a lowly missionary. I have since heard that Germany had not many profounder scholars than my old friend, but unfortunately his zeal for freedom brought him into disfavor with the highest authorities—the unification of Germany was at that time a mere dream—and he was driven from his native land before his wife had left her youth. Expelled from his own country and filled with a spirit of genius that drove him to action, the refugee turned his talents to that most laborious and thankless of all worldly pursuits, and became a missionary among the most untamed tribes of South Africa. He labored tirelessly in his new calling, but I fear he did not convert many. Nevertheless, his condition in the land of the Tsulu seemed good. His constant rebukes against cruelty and injustice made the king more cautious in slaughtering his subjects, for he thought that the deed would be known to the outside world through the missionary; and so he, though indirectly, saved a few lives. But though my old friend only succeeded in making Christians in a bad way, he gained for himself a great reputation for his medical skill. This was the course of life to which he had given himself in his youth; and the king had more than once fallen into a debt of gratitude to the white priest, when he had relieved his bodily pains.

But notwithstanding his gratitude to the missionary’s medical assistance, Cetewayo, in his heart—if he had such a faculty—secretly detested Beidermann and his whole estate. Many of the missionaries were thoroughly senseless, and tried to enforce reforms by force, which, if carried out, would have greatly weakened the king’s power. My old friend was not one of these men; but the public manner in which he denounced tyranny was very bitter to the despot; and the contempt with which he treated the Tsululai priests, or magicians, earned him the wrath of this estate also.

For years the king had groaned under the missionary yoke, and had resolved in his mind that at the first convenient opportunity the strangers should be expelled from his country; and at the same time he intended to rescind the promises which he had made to the British Government on his accession to the throne of the Tsulu; after which he might again tread, fearlessly and unhindered, the same path of bloodshed which his worthy uncles Chaka and Dingaon had begun. It was no sudden rashness that led his purpose there, no savage whim or childish tantrum, but a firm and determined determination to free himself from the fetters of civilization, a determination which had matured in careful deliberation, and which had been the object of many years of patient preparation. Taking advantage of the laxity with which the gunpowder law was enforced during the first raid on the Transvaal diamond fields, the King had obtained a fine stock of guns; and as soon as another large consignment reached him from Delagoa Bay, he thought it was time to break peace with the British, and, well aware that some delay was necessary before our Government could decide to take action, Cetewayo did not listen with any distaste to the rancor of his witch-priest against Arnold Beidermann; on the contrary, their favorable reception made them seem credible even to his advisers. The missionary had been to a Portuguese merchant, and so he could take as his excuse the latter’s prohibition of obtaining ammunition. True, he went to help the merchant who was suffering from a fever, but that did not help matters. Here was an opportunity for the king to get rid of the man he hated, and at the same time to get some cattle. And so, rising from his throne, the monarch solemnly declared:

“Let twenty oxen be killed and my warriors feast. Tomorrow they will march against the Dutch, and the white priest will be driven out of the country.”

This decision was received by the advisors with unlimited expressions of favor, at the echo of which the king retired to his harem, to remain there unseen until the next day.

Chapter 4.

Forewarned and equipped.

While the events related in the preceding chapter were taking place, the inhabitants of the Transvaal settlement were carelessly going about their usual business. They were grazing their cattle, hoeing up plots of land for cultivation and for laying out corn or Indian barley, making embankments, forming them into reservoirs for water, for this precious substance must be carefully preserved in South Africa; implementing new methods of irrigation to promote the growth of the grain, and trying all sorts of other means which experience had shown the Boers to be suitable for making their cultivation bear fruit.

It is unnecessary to explain to the reader that I was not present at the meeting held at Cetewayo, where it was decided to drive Arnold Beidermann out of the country and to attack Pieter Dirksen’s house. The various circumstances which occurred there were afterwards related to me in detail, for the Tsululainen is endowed with a wonderful memory, together with a slippery tongue, and he can still, after many years, relate every word of the important discussion which took place in his presence. Thus, if, speaking precisely, I have deviated somewhat from the order in which the facts came to my knowledge, I have nevertheless preserved the chronological sequence in which the incidents followed one another.

A couple of weeks had passed since the hunt in which the king’s messenger had met his end, and my plant-brother had fully recovered from the frightful shock he had received in this state. We had often spoken among ourselves of the fate that would befall him if Cetewayo actually carried out his threat and succeeded in getting the fugitives into his hands; and I remarked to both Ula and Landela that it would be much wiser for them to move away for a time from the immediate vicinity of the frontier and seek hospitality among the Schwazi people, with whom the king of the Tsulu was at war. My own land on Mount Eloya is in fact, like Pieter Dirksen’s new-found land, in the Transvaal, but Cetewayo still claimed it for himself; and the knowledge that the refugees were staying in a country which he—rightly or wrongly—regarded as his own would arouse the autocrat’s vengeance and probably bring sorrow to the Dutchman’s and his family’s affairs.

My old nurse and her son both realized the truth of these thoughts, and having calmly made all the preparations for the journey, they waited for Pieter Dirksen, to express their thanks for his hospitality and to bid him farewell, before they set off to sink into that immense sea of hay. With all his colloquialism, Boeri, however, had a clear idea of the purpose of this sudden departure, and I now saw his rigid nature deeply moved.

“You can’t leave,” he growled, slamming his massive fist on the table with a force that sent tin plates flying.

“You are my guests, and I will not let you go, no, on the threat of all the witches who roam between this place and Cape Town, I will not. Or what do you say, Henrik, Karel, would you let the boy who stood between your father and the lion go into the wilderness because of the threats of a forest scoundrel like Cetewayo? No, by—! we are not mothers to be commanded by any man or to be frightened out of our wits. Put away your weapons, and let me hear no more of your departure.”

I had never seen my master in such a state of excitement before. Gratitude to my fellow-plant, combined with a stubborn stubbornness, was the fundamental reason for this unexpected insistence on an inch, which, if carried out, would very probably have prevented the consequences which it is my duty to relate hereafter. Once he had set his mind to something, Pieter was as stubbornly single-minded as the white rhinoceros of his native plains; and when his opinion on this matter met with the unanimous approval of the family, longer speeches were of no avail, and Ula—greatly pleased by such an expression of gratitude—remained in the new dwelling.

My intention had been to set out for Mount Eloya, to begin building my dwellings there, which would be more comfortable than is usually seen in a remote settlement; but I thought it wiser to let a week or so pass, for if Cetewayo really attempted to carry out his threats against Dirksen, the raiding party would certainly visit my settlement, and find a convenient pastime in burning down the buildings I had just finished. By uniting our companions, we can muster a force strong enough to hold the band of wildlings in check until the government should come to our aid; on the other hand, if we were separated, we would both be easy prey.

And so I lingered at the new residence, making all sorts of excuses for neglecting my original plan, for I did not dare to directly confess the real reasons that held me back, because I knew very well that the brisk old man would laugh and mock my caution—and I amused myself by hunting with Ula. In this untamed district all kinds of game were still to be found in the fields, and a three-hour ride always took us into regions where it was not difficult to meet buffalo, giraffe, innumerable antelope, and even an occasional elephant. Although I lived as a guest in the house of old Pieter Dirksen, I had servants and companions of my own to look after my cattle, my carriages, and my other possessions; so that, being away from home every day on these excursions, nothing was left to decay. I didn’t enjoy farming at all, and by setting the table with fresh wild game, I saved a decent amount of my own and Dutchman’s roast beef.